Friday, October 27, 2006

Molly departs

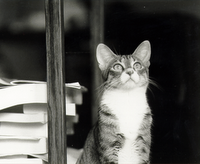

First Eric Newby--and now Kerry's chubby, cheerful companion of the last decade and half, Molly. The Molecule, as she was often known (yes, there were other nicknames, hundreds of them, but it would require a separate blog to list them all) could be a little skittish if you approached her too quickly. Given time and elbow room, she was an amiable creature, never more so than when I was ferrying her back home from one veterinarian or another. Once Kerry had unzipped the roof of the Sherpa, Molly would stick her perfectly circular head out and study the passing the terrain with an appealing gravity--with, you might say, a lust for life. She had big ears and a two-tone nose. Despite her avoirdupois, she had a dainty way of moving around Kerry's apartment, not unlike Christopher Smart's famous feline, Jeoffrey:

First Eric Newby--and now Kerry's chubby, cheerful companion of the last decade and half, Molly. The Molecule, as she was often known (yes, there were other nicknames, hundreds of them, but it would require a separate blog to list them all) could be a little skittish if you approached her too quickly. Given time and elbow room, she was an amiable creature, never more so than when I was ferrying her back home from one veterinarian or another. Once Kerry had unzipped the roof of the Sherpa, Molly would stick her perfectly circular head out and study the passing the terrain with an appealing gravity--with, you might say, a lust for life. She had big ears and a two-tone nose. Despite her avoirdupois, she had a dainty way of moving around Kerry's apartment, not unlike Christopher Smart's famous feline, Jeoffrey:For God has blessed him in the variety of his movements.I assume she's now in some four-legged Heaven with plenty of catnip, turkey breast, sunlight, and raggedy armchairs. But she'll be missed.

For, tho' he cannot fly, he is an excellent clamberer.

For his motions upon the face of the earth are more than any other quadruped.

For he can tread to all the measures upon the music.

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Eric Newby departs

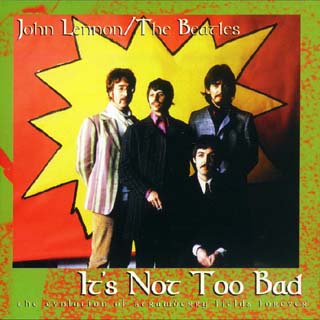

I was tremendously sad to read about the death of Eric Newby. It's true that the author, editor, and inveterate traveler crammed an awful lot of mileage into his 86 years. But Newby was something extraordinary: a missing link between the great Britannic wanderers of the Victorian era and such contemporary jungle nuts as Redmond O'Hanlon. And the funny thing is, he nearly missed his vocation altogether. For more than a decade following the end of World War II, Newby toiled away in the British fashion industry, peddling some of the ugliest clothes on the planet. (He was eventually to chronicle this period in Something Wholesale: My Life and Times in the Rag Trade.)

Fortunately, he reached the end of his haute-couture tether in 1956. At that point, with the sort of sublime impulsiveness that's forbidden to fictional characters but endemic to real ones, he decided to visit a remote corner of Afghanistan, where no Englishman had planted his brogans for at least 50 years. What's more, he recorded his adventure in a classic narrative, A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush. The title, of course, is a fine example of Newby's habitual self-effacement, since his journey--which included a near-ascent of the 19,800-foot Mir Samir--was anything but short.

Fortunately, he reached the end of his haute-couture tether in 1956. At that point, with the sort of sublime impulsiveness that's forbidden to fictional characters but endemic to real ones, he decided to visit a remote corner of Afghanistan, where no Englishman had planted his brogans for at least 50 years. What's more, he recorded his adventure in a classic narrative, A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush. The title, of course, is a fine example of Newby's habitual self-effacement, since his journey--which included a near-ascent of the 19,800-foot Mir Samir--was anything but short.

Newby was always a less acidulous writer than, say, Waugh (who contributed a short preface to his first book). But he was among the keenest and funniest of literary travelers, and unlike many of his colleagues, he never fell back on cranky solipsism or coy misanthropy. In fact he relished other people: his books are filled with indelible portraiture of his companions. A Short Walk introduced us to the madcap Hugh Carless and to Newby's wife, Wanda (who would play a starring role in such subsequent chronicles as Slowly down the Ganges). In Love and War in the Apennines we seem to meet at least half the inhabitants of a tiny Italian village--and not a single one conforms to the lazy image of the carefree contadino. For Newby, a human being was truly terra incognita, and he explored each one anew.

Sound bites don't really do justice to Newby's peregrinations: they require a sense of momentum from the reader. Yet I couldn't resist quoting a couple of examples. First, to get a sense of his comic register, listen to the author get in his digs at Britain's special relationship with the violence-prone Abdur Rahman of Nuristan:

Finally, a personal note. For the past few months, I had been interested in interviewing Eric Newby. The prospect of exchanging a few words with this brilliant man--assuming I could catch him in a stationary position--already had me hyperventilating. I explored the idea with a couple of magazine editors, and kept reminding myself to contact somebody at Lonely Planet. (It was this rough-and-ready travel publisher who did us all the great service of reprinting the bulk of Newby's work in paperback. Three cheers!) Now, of course, it's too late. I suppose the lesson is the same one we seem incapable of learning, year after year: carpe diem. Seize the day. Well, Newby certainly did.

Finally, a personal note. For the past few months, I had been interested in interviewing Eric Newby. The prospect of exchanging a few words with this brilliant man--assuming I could catch him in a stationary position--already had me hyperventilating. I explored the idea with a couple of magazine editors, and kept reminding myself to contact somebody at Lonely Planet. (It was this rough-and-ready travel publisher who did us all the great service of reprinting the bulk of Newby's work in paperback. Three cheers!) Now, of course, it's too late. I suppose the lesson is the same one we seem incapable of learning, year after year: carpe diem. Seize the day. Well, Newby certainly did.

Fortunately, he reached the end of his haute-couture tether in 1956. At that point, with the sort of sublime impulsiveness that's forbidden to fictional characters but endemic to real ones, he decided to visit a remote corner of Afghanistan, where no Englishman had planted his brogans for at least 50 years. What's more, he recorded his adventure in a classic narrative, A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush. The title, of course, is a fine example of Newby's habitual self-effacement, since his journey--which included a near-ascent of the 19,800-foot Mir Samir--was anything but short.

Fortunately, he reached the end of his haute-couture tether in 1956. At that point, with the sort of sublime impulsiveness that's forbidden to fictional characters but endemic to real ones, he decided to visit a remote corner of Afghanistan, where no Englishman had planted his brogans for at least 50 years. What's more, he recorded his adventure in a classic narrative, A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush. The title, of course, is a fine example of Newby's habitual self-effacement, since his journey--which included a near-ascent of the 19,800-foot Mir Samir--was anything but short.Newby was always a less acidulous writer than, say, Waugh (who contributed a short preface to his first book). But he was among the keenest and funniest of literary travelers, and unlike many of his colleagues, he never fell back on cranky solipsism or coy misanthropy. In fact he relished other people: his books are filled with indelible portraiture of his companions. A Short Walk introduced us to the madcap Hugh Carless and to Newby's wife, Wanda (who would play a starring role in such subsequent chronicles as Slowly down the Ganges). In Love and War in the Apennines we seem to meet at least half the inhabitants of a tiny Italian village--and not a single one conforms to the lazy image of the carefree contadino. For Newby, a human being was truly terra incognita, and he explored each one anew.

Sound bites don't really do justice to Newby's peregrinations: they require a sense of momentum from the reader. Yet I couldn't resist quoting a couple of examples. First, to get a sense of his comic register, listen to the author get in his digs at Britain's special relationship with the violence-prone Abdur Rahman of Nuristan:

Officially his subsidy had just been increased from 12,000 to 16,000 lakhs of rupees. To the British he had fully justified their selection of him as Amir of Afghanistan and, apart from the few foibles remarked by Lord Curzon, like flaying people alive who displeased him, blowing them from the mouths of cannon, or standing them up to the neck in pools of water on the summits of high mountains and letting them freeze solid, he had done nothing to which exception could be taken.Zing! (That brief paragraph is, alas, weirdly apposite to America's own Afghan quagmire.) But here's another bit, from Slowly Down the Ganges, which shows off Newby's lyrical eye for the terrain:

At about six the sky to the east became faintly red; then it began to flame and the moon was extinguished; clouds of unidentifiable birds flew high overhead; a jackal skulked along the far shore and, knowing itself watched, went up the bank and into the trees; mist rose from the wet grass on the islands on which the shisham trees stood, wrapped like precious objects in their bandages of dead grass.No gushy exoticism, no fat, no poetry on stilts. Just curiosity and precision, which are among the ultimate tools for any writer, even the kind that seldom vacates his or her armchair.

Finally, a personal note. For the past few months, I had been interested in interviewing Eric Newby. The prospect of exchanging a few words with this brilliant man--assuming I could catch him in a stationary position--already had me hyperventilating. I explored the idea with a couple of magazine editors, and kept reminding myself to contact somebody at Lonely Planet. (It was this rough-and-ready travel publisher who did us all the great service of reprinting the bulk of Newby's work in paperback. Three cheers!) Now, of course, it's too late. I suppose the lesson is the same one we seem incapable of learning, year after year: carpe diem. Seize the day. Well, Newby certainly did.

Finally, a personal note. For the past few months, I had been interested in interviewing Eric Newby. The prospect of exchanging a few words with this brilliant man--assuming I could catch him in a stationary position--already had me hyperventilating. I explored the idea with a couple of magazine editors, and kept reminding myself to contact somebody at Lonely Planet. (It was this rough-and-ready travel publisher who did us all the great service of reprinting the bulk of Newby's work in paperback. Three cheers!) Now, of course, it's too late. I suppose the lesson is the same one we seem incapable of learning, year after year: carpe diem. Seize the day. Well, Newby certainly did.Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Odds and ends II: Augustus, Planet HOM

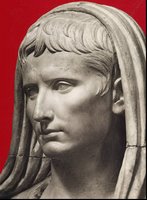

I shouldn't be blogging again, but while I was just eating lunch (a tasty and nutritious hot dog, if you must know), I started reading Anthony Everitt's new Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor. What I learned right off the bat was that the middle-aged emperor and pontifex maximus was something of a control freak, whose strict regulation of his public persona would impress even George W. Bush's handlers:

I shouldn't be blogging again, but while I was just eating lunch (a tasty and nutritious hot dog, if you must know), I started reading Anthony Everitt's new Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor. What I learned right off the bat was that the middle-aged emperor and pontifex maximus was something of a control freak, whose strict regulation of his public persona would impress even George W. Bush's handlers:Although Augustus was perfectly capable of speaking extempore in public, he was always afraid of saying too much, or too little. So he not only carefully drafted his speeches to the Senate and read them out from a manuscript, but he also wrote down in advance any important statement he planned to make to an individual, and even to [his wife] Livia (it says something of her own clerical tidy-mindedness that she kept and filed all Augustus' written communications with her).That's what love is for! When he wasn't recording his talking points on a piece of parchment, Augustus drank and ate in moderation: if he felt like pigging out, he ate a few grapes or a slice of bread soaked in water. And what about relaxation? No orgiastic fun on the triclinium for this emperor: "In the afternoon the princeps could enjoy some leisure. He used to lie down for a while without taking his clothes or shoes off. He had a blanket spread over him, but left his feet uncovered."

Another small point. The traffic to this blog is fairly light--I would call it a distinguished trickle--but I continue to be impressed by how far-flung it is. When I glanced at the referral log shortly before noon, I saw that the last twenty visitors hailed not only from the United States but from Belgium (Wezembeek-Oppem), Japan (Kanagawa), Canada (Halifax), England (London), India (Lucknow), Holland (Landsmeer), Bulgaria (Pleven), and Australia (Donvale). Come one, come all. And welcome!

Odds and ends: the indefatigable Mister Amis, Lennon's house, It's Not Too Bad, Takemitsu, death of the book review

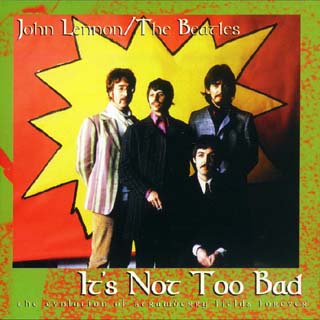

Having been soundly thrashed for Yellow Dog, and sorrowfully paddled for The House of Others (in the United Kingdom, anyway), Martin Amis is soldiering on. As he told Mike Collett-White at Reuters, he's already "repulsively far advanced with another novel. I'm almost 100,000 words into another." The new book seems to be a roman à clef--exactly the sort of thing that will get Amis drawn and quartered at the Groucho Club. Yet The Pregnant Widow, like the author's latest production, is also a tale of revolution: more specifically, the sexual revolution (if that's what it was) of the Sixties and Seventies. Here's Amis: It was at Kenwood, too, that Lennon made his second round of demo recordings for "Strawberry Fields Forever," now collected on a superb bootleg called It's Not Too Bad. The disc actually begins with some crude sketches Lennon taped while he was in Santa Isabel, Spain, filming Richard Lester's How I Won The War. Next comes the stuff he recorded upstairs at Kenwood, using a pair of Brennell reel-to-reel machines. It's amazing how fast the song snapped into focus. What's even more amazing is the first take the Beatles recorded at EMI on November 24, 1966. Geoff Emerick describes that long evening in his recent memoir, Here, There and Everywhere:

It was at Kenwood, too, that Lennon made his second round of demo recordings for "Strawberry Fields Forever," now collected on a superb bootleg called It's Not Too Bad. The disc actually begins with some crude sketches Lennon taped while he was in Santa Isabel, Spain, filming Richard Lester's How I Won The War. Next comes the stuff he recorded upstairs at Kenwood, using a pair of Brennell reel-to-reel machines. It's amazing how fast the song snapped into focus. What's even more amazing is the first take the Beatles recorded at EMI on November 24, 1966. Geoff Emerick describes that long evening in his recent memoir, Here, There and Everywhere:

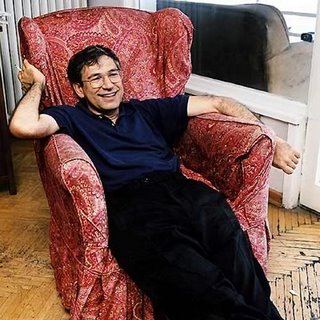

On a different musical note, I was foolishly trawling the Web late last night and came across Jan Swafford's Slate article about Toru Takemitsu. Having read and admired Swafford's bio of Charles Ives--although I now can't seem to locate it in my landfill-sized book collection--I was eager to learn about his nominee for the Best Film Composer Ever. Takemitsu, who wrote not only reams of music but a series of detective novels to boot, sounded like my cup of tea. I had to hear some of his stuff right now. And that, ladies and germs, is where iTunes comes in handy. After quickly scoping out what was available, I downloaded A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden. On this laughably inexpensive, pristinely recorded disc (God bless you, Naxos), the excellent Marin Alsop leads the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra through five pieces, from "Solitude Sonore" (1958) to "Spirit Garden" (1994). What gorgeous music! On these pieces, at least, Takemitsu steers clear of the hummable melody--what we get are vast, unpredictable clouds of orchestration. Some of the gentle, chamber-music-like passages for reeds, flute, and percussion remind me of Mahler. As Swafford points out, that's exactly what Kurosawa requested during the filming of Ran:

On a different musical note, I was foolishly trawling the Web late last night and came across Jan Swafford's Slate article about Toru Takemitsu. Having read and admired Swafford's bio of Charles Ives--although I now can't seem to locate it in my landfill-sized book collection--I was eager to learn about his nominee for the Best Film Composer Ever. Takemitsu, who wrote not only reams of music but a series of detective novels to boot, sounded like my cup of tea. I had to hear some of his stuff right now. And that, ladies and germs, is where iTunes comes in handy. After quickly scoping out what was available, I downloaded A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden. On this laughably inexpensive, pristinely recorded disc (God bless you, Naxos), the excellent Marin Alsop leads the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra through five pieces, from "Solitude Sonore" (1958) to "Spirit Garden" (1994). What gorgeous music! On these pieces, at least, Takemitsu steers clear of the hummable melody--what we get are vast, unpredictable clouds of orchestration. Some of the gentle, chamber-music-like passages for reeds, flute, and percussion remind me of Mahler. As Swafford points out, that's exactly what Kurosawa requested during the filming of Ran:

Finally: the book review section seems to be on the verge of extinction. How am I going to make a living? Oh, right: blogging.

Writing about revolution, Alexander Herzen said normally one should be pleased when one order gives way to another, but it's not a child you're left with after a revolution, you're left with a pregnant widow, and there will be much terror and tribulation before that child is born. The father is dead, the child is not yet born. I think that is what has happened to feminism. It's only now in its second trimester. The baby isn't there yet. Dad is dead--patriarchy has gone, but the baby isn't there yet.Hold onto your hats, folks. And if you've got any extra pocket change, put in your bid on John Lennon's former six-bedroom mansion in Weybridge, Surrey, now on sale with a floor of 5.95 million pounds ($11.1 million). Described by one Beatles Fan Club bigwig as "a nice house, in the stockbroker belt," it was the setting for a certain amount of extramarital shenanigans:

In 1968, while Cynthia was vacationing in Greece, Lennon invited Ono to the house known as Kenwood. The pair stayed up all night taking drugs and collaborated on what was to become the record album Two Virgins, released later that year. It was also the first time the pair consummated their affair. Cynthia Lennon...returned early from her vacation to find Ono both in residence at the house and wearing her bathrobe. The property was sold in the divorce settlement.

It was at Kenwood, too, that Lennon made his second round of demo recordings for "Strawberry Fields Forever," now collected on a superb bootleg called It's Not Too Bad. The disc actually begins with some crude sketches Lennon taped while he was in Santa Isabel, Spain, filming Richard Lester's How I Won The War. Next comes the stuff he recorded upstairs at Kenwood, using a pair of Brennell reel-to-reel machines. It's amazing how fast the song snapped into focus. What's even more amazing is the first take the Beatles recorded at EMI on November 24, 1966. Geoff Emerick describes that long evening in his recent memoir, Here, There and Everywhere:

It was at Kenwood, too, that Lennon made his second round of demo recordings for "Strawberry Fields Forever," now collected on a superb bootleg called It's Not Too Bad. The disc actually begins with some crude sketches Lennon taped while he was in Santa Isabel, Spain, filming Richard Lester's How I Won The War. Next comes the stuff he recorded upstairs at Kenwood, using a pair of Brennell reel-to-reel machines. It's amazing how fast the song snapped into focus. What's even more amazing is the first take the Beatles recorded at EMI on November 24, 1966. Geoff Emerick describes that long evening in his recent memoir, Here, There and Everywhere:The Beatles weren't ever especially fast at working out parts, and this night followed the usual pattern: several hours were spent routining the song, deciding who was going to play what instrument, and figuring out the exact patterns and notes they would play. Paul was still having a whale of a time with the Mellotron, so he decided he would man it during the backing track. Ringo busied himself by arranging towels over his snare drum and tom-toms in order to give them a distinctive muffled tone. Off in a corner, George Harrison was experimenting with his new toy--slide guitar--practicing the long, Hawaiian-style swoops he planned to play on his electric guitar, punctuating John's more straightforward rhythm part. Following a long period of rehearsal, they finally decided to make a first stab at recording a backing track.It's interesting to glimpse George Harrison discovering the slide guitar, which would be his sonic signature throughout the rest of life. The towels throw some new light on Ringo's thudding drum sound. In any case, the first take was an absolute beauty: much quieter and more wistful than the final product. It remained in the EMI vaults until 1996, when it was released on Anthology 2. But even there, George Martin polished up the rough edges and inexplicably mixed out the backing vocals, which appear in their full glory on It's Not Too Bad.

On a different musical note, I was foolishly trawling the Web late last night and came across Jan Swafford's Slate article about Toru Takemitsu. Having read and admired Swafford's bio of Charles Ives--although I now can't seem to locate it in my landfill-sized book collection--I was eager to learn about his nominee for the Best Film Composer Ever. Takemitsu, who wrote not only reams of music but a series of detective novels to boot, sounded like my cup of tea. I had to hear some of his stuff right now. And that, ladies and germs, is where iTunes comes in handy. After quickly scoping out what was available, I downloaded A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden. On this laughably inexpensive, pristinely recorded disc (God bless you, Naxos), the excellent Marin Alsop leads the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra through five pieces, from "Solitude Sonore" (1958) to "Spirit Garden" (1994). What gorgeous music! On these pieces, at least, Takemitsu steers clear of the hummable melody--what we get are vast, unpredictable clouds of orchestration. Some of the gentle, chamber-music-like passages for reeds, flute, and percussion remind me of Mahler. As Swafford points out, that's exactly what Kurosawa requested during the filming of Ran:

On a different musical note, I was foolishly trawling the Web late last night and came across Jan Swafford's Slate article about Toru Takemitsu. Having read and admired Swafford's bio of Charles Ives--although I now can't seem to locate it in my landfill-sized book collection--I was eager to learn about his nominee for the Best Film Composer Ever. Takemitsu, who wrote not only reams of music but a series of detective novels to boot, sounded like my cup of tea. I had to hear some of his stuff right now. And that, ladies and germs, is where iTunes comes in handy. After quickly scoping out what was available, I downloaded A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden. On this laughably inexpensive, pristinely recorded disc (God bless you, Naxos), the excellent Marin Alsop leads the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra through five pieces, from "Solitude Sonore" (1958) to "Spirit Garden" (1994). What gorgeous music! On these pieces, at least, Takemitsu steers clear of the hummable melody--what we get are vast, unpredictable clouds of orchestration. Some of the gentle, chamber-music-like passages for reeds, flute, and percussion remind me of Mahler. As Swafford points out, that's exactly what Kurosawa requested during the filming of Ran:For the epic battle sequence of Ran, Kurosawa's version of King Lear, the director told Takemitsu he wanted something like Mahler. What Takemitsu gave him is and isn't Mahler. It has a big orchestral sound spread over wide spaces and a Mahleresque sense of doom, but the music is modern, keening with tragedy and horror, utterly unclichéd, as indelibly wedded to the images as the shower scene in Psycho. Together, the music and visuals make the battle in Ran, I propose, one of the most eloquent sequences in all of film.Regrettably, that music is not on this disc. I'll have to track it down. Hell, I'll have to watch Ran again.

Finally: the book review section seems to be on the verge of extinction. How am I going to make a living? Oh, right: blogging.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Picture this

Yesterday the Los Angeles Times ran my review of Marjane Satrapi's latest, Chicken With Plums. This is the first time I've reviewed a graphic novel. I have my reservations about the genre--although I've relished work by (for example) Art Spiegelman and Charles Burns, something like the recent Classics Comics adaptation of the 9/11 Report makes me wonder whether we're turning into a nation of absolute cretins. That said, the Satrapi was delightful. Here's how I began:

You can read the rest here.Cartoonists, like novelists, can be roughly divided into maximalists (who work by dogged addition) and minimalists (who work by delicate subtraction). Marjane Satrapi falls into the latter camp. Her inky little panels are marvels of simplicity, with a decorative twist derived in part from Persian miniatures, and many of her most memorable sequences are awash in basic black.

Yet it's amazing to see how much complexity and narrative cunning Satrapi crams into her seemingly artless images. In Persepolis (2003) and Persepolis 2 (2004), she pulled off a formidable bit of binocular vision, merging her childhood with the tormented history of modern Iran. There was nothing didactic about these books. They were fresh, warm, often whimsical, even as the shadow of dour fundamentalism fell over the author's middle-class existence. Nor did she lower the bar in Embroideries, published in 2005. Again, the topic was deadly serious --sexual politics, in the Middle East and elsewhere--but Satrapi approached it via a round robin of chatty (and catty) anecdotes.

Saturday, October 14, 2006

Call me Orhan

I've blogged about Orhan Pamuk on several earlier occasions (including here and here), and was delighted by the news from the Swedish Academy. To be honest, I thought he still might be considered too wet behind the ears, and was putting my own bet on Adonis, mostly for geopolitical reasons. But I was wrong. In any case, the Los Angeles Times asked me to write an appreciation, which they ran this morning. I began this way:

I've blogged about Orhan Pamuk on several earlier occasions (including here and here), and was delighted by the news from the Swedish Academy. To be honest, I thought he still might be considered too wet behind the ears, and was putting my own bet on Adonis, mostly for geopolitical reasons. But I was wrong. In any case, the Los Angeles Times asked me to write an appreciation, which they ran this morning. I began this way:Back in April, when Salman Rushdie introduced Orhan Pamuk to a rapt audience at New York's Cooper Union, he joked about his Turkish colleague's growing stash of prizes. "Orhan is the winner of the heaviest award in the world," Rushdie noted, alluding to Ireland's IMPAC. "You can kill somebody with it." The crowd chuckled appreciatively. But now Pamuk has won an even weightier honor: the Nobel Prize.You can read the rest here. Me, I'm going to dip into Maureen Freely's revised translation of The Black Book, which I bought in paperback on Thursday. While the young, bearded clerk at Borders rang up my purchase, I said, "You must be selling plenty of these." He glanced at the book and said,"I don't think so. Why?" Drat.

Pamuk, who is currently a visiting fellow at Columbia University, has long been mentioned as a Nobel contender. Indeed, the oddsmakers at Ladbrokes in Britain initially tipped him as a 7-to-1 favorite--no mean accomplishment for a writer whose work hadn't even appeared in English until 1991.

Some, to be sure, considered the 54-year-old Pamuk too young for an award that is customarily the capstone of a distinguished career. And his legal travails with the Turkish government--which tried him earlier this year for "insulting Turkishness" before dropping the charges--amounted to something of a wild card. The Swedish Academy likes to be seen as aesthetically fastidious, unwilling to wade into the political muck. Yet it did give the nod last year to Harold Pinter (a vocal critic of his native Britain) and, in 2004, to Elfriede Jelinek (a vocal critic of her native Austria), so Pamuk's recent history of dissent probably didn't hurt.

Monday, October 09, 2006

A-list survivor, etc

In The Observer (via Literary Saloon), Jonathan Beckman slaps Verso on the wrist for the company's bait-and-switch publication of Auschwitz Report by Primo Levi and Leonardo De Benedetti. Beckman does acknowledge the book's value as a historical curiosity. But as he points out, the 48-page document, written shortly after both authors were liberated from the camp in the summer of 1945, was mostly De Benedetti's work. (In her biography, Carole Angier calls it "a truly impersonal, factual report.") So the publisher has been naughty indeed to pitch the book as a precursor to Levi's masterly Survival in Auschwitz:

In The Observer (via Literary Saloon), Jonathan Beckman slaps Verso on the wrist for the company's bait-and-switch publication of Auschwitz Report by Primo Levi and Leonardo De Benedetti. Beckman does acknowledge the book's value as a historical curiosity. But as he points out, the 48-page document, written shortly after both authors were liberated from the camp in the summer of 1945, was mostly De Benedetti's work. (In her biography, Carole Angier calls it "a truly impersonal, factual report.") So the publisher has been naughty indeed to pitch the book as a precursor to Levi's masterly Survival in Auschwitz:De Benedetti's name does not sell books. So Verso has dolled this up as the work of Levi, blazoning his name on the front of the book, at least five times bigger than the words "with Leonardo De Benedetti." Levi alone merits a photo and biographical note on the dust jacket. Unforgivably, the only illustration on the cover is Levi's distinctive bottle-lensed glasses, guaranteeing the reader the "authentic" experience with an A-list Holocaust survivor. Piggybacking sales on Levi's name is tasteless, but to misrepresent the Holocaust's historical record is insidious, when absolute fidelity to truth is the only bulwark for sustaining remembrance against the gainsayers. The contortions of the introduction, which attempts to connect the Auschwitz Report and Levi's later work, are spurious and crass.Beckman notes one surprise: Auschwitz and its satellite camps boasted more medical facilities than one might have expected, including an "otorhinology and ophthamology clinic." He's certainly not naive enough to chalk this up to compassion: the Germans kept the prisoners alive only in order to squeeze more labor out of them. Yet I was reminded of a ghastly passage I read a couple of weeks ago in Eugen Kogon's The Theory and Practice of Hell, a classic 1950 account of the camps recently reprinted in paper by FSG. The author (below) was a prisoner in Buchenwald, and in one chapter, called "Recreation," he recalls:

This sort of thing leaves me speechless. So does the news that masochistic magician and escape artist David Blaine has Primo Levi's number tattooed on his arm. Blaine is talented, buff, charismatic. But to confuse his high-end carnival act, with its splashy confinements in a fishbowl or block of ice, to the lethal servitude of a concentration camp, is tasteless beyond measure. If he truly wanted a string of digits on his arm, he should have chosen something more appropriate--say, Evil Knievel's social security number.In May 1941 Buchenwald began to enjoy a unique form of relaxation--motion pictures. The Buchenwald movie theater was the first in a German concentration camp, and it seems to have remained the only one. Permission to establish it was wheedled from the SS by the prisoner foreman of the photo section, who dwelt on the enormous profits to be made from exhibiting, at thirty pfennigs a head, ancient, worn-out films costing but thirty-five marks apiece... The procurement of films from the UFA Company in Berlin was not always an easy matter. SS men had to be bribed, and every strategem had to be employed to keep on sending couriers to the capital. Both entertainment and documentary films were offered, weekly or biweekly, with longer interruptions.

Many prisoners drew strength from the few hours of illusion given them by the movies; others, faced with the ever-present misery in camp, could never bring themselves to attend, especially since the theater was used also as a place of punishment. The fact that it was used so sprang from no particular sadistic streak on the part of the SS: the hall merely happened to be suitable and convenient--spacious and gloomy, the ideal place for the whipping rack, which was carried out to the roll call area only when a special show was put on. The movie theater also provided storage space for the gallows and the posts, inserted in special holes, on which prisoners were strung up.

Friday, October 06, 2006

Viva Trapido

According to the Guardian, the personal library of the late Princess Margaret has now been boxed up and sold on the cheap. (The article by Maev Kennedy appears under the rubric, "Special Report: The Monarchy." Classy!) Not surprisingly, the author dwells on some of the inscriptions. The princess's copy of Swedenborg's The Delights of Wisdom Concerning Conjugial Love: After which Follows the Pleasures of Insanity Concerning Scortatory Love was inscribed To Margaret, Princess of the Realm, and signed Wm. Other inscribed items, such as Sir Rupert John's scholarly monograph Racism and its Elimination, appear never to have been read. What really got my goat, though, was this sentence:

Each [book]--even the dogeared Mickey Spillane thriller, a 1963 Corgi paperback, and Barbara Trapido's Temples of Delight, "a shimmering summer read"--carried an elegant bookplate, printed: "From the Apartment of HRH the Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon, 1930-2002."Snigger all you like at Mickey Spillane, who's apparently being dissed for appearing in an infra-dig Corgi softcover. But don't dump on Barbara Trapido. She won the Whitbread for Brother of the More Famous Jack, and one of her subsequent novels, The Travelling Horn Player, is as intricate, funny, and rueful as anything I've read in years. She is not, emphatically not, some sort of Danielle Steele in jodhpurs. So there.

Thursday, October 05, 2006

Happy birthday, KJP

I'm told by reliable sources that today is the birthday of Kelly Joe Phelps. In theory I swore off the whole YouTube thing a while ago, but I'll make an exception for this splendid clip from the Jools Holland Show. At the very peak of his knit-cap-and-lap-slide phase, the performer slips, slithers, and moans his way through "Piece by Piece," leaving the original version (from Shine Eyed Mister Zen) in the dust. There's another live version floating around on the Internet, with none other than Bill Frisell riding shotgun on electric guitar, but even that falls short of the intensity on display here:

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Mind if I tag along?

Kelly Jane Torrance (one of the few people ever to call me a litterateur) passed this on to me. I'm going to answer as swiftly as possible, because if I start having second thoughts, this could take all day. Here we go!

1. One book that changed your life?

Oh, that's easy: Johnny Tremain by Esther Forbes, which I read when I was eight years old. Prior to that I had never really immersed myself in the imaginative world of a book--even my favorite Hardy Boys novels, like The Mystery of the Old Mill, seemed slightly ersatz. But Johnny Tremain swallowed me up. I read the second half while we were on a family vacation, and in a motel overlooking the Little Pigeon River in Tennessee, while I was pondering the molten silver that had spilled onto Johnny's hand, I walked smack into a sliding glass door. No permanent injuries.

2. One book that you have read more than once?

I've read many books more than once. A good example would be Morte D'Urban by J.F. Powers, with its quicksilver alternation of pathos and ecclesiastical comedy. On the other hand, I'm afraid I've spent nearly as much time with Hank Bordowitz's Bad Moon Rising: The Unofficial History of Creedence Clearwater Revival. Once a geek, always a geek--but clearly something about John Fogerty's crash-and-burn cycle got under my skin.

3. One book you would want on a desert island?

A long one, needless to say, so I'll choose The Divine Comedy. I'd like a version with facing text in Italian, so I could really brush up on those subjunctive constructions. Or maybe a complete Shakespeare. Or maybe Johnny Tremain.

4. One book that made you cry?

These days I'm more prone to cry when reading, as if the tears of things are always on tap. One example that comes to mind is Michael Downing's vastly underrated Perfect Agreement. Also, this passage from W.G. Sebald's The Emigrants, which I suppose will mean nothing out of context: "Three quarters of an hour later, not wanting to miss the landscape around Lake Geneva, which never fails to astound me as it opens out, I was just laying aside a Lausanne paper I'd bought in Zurich when my eye was caught by a report that said the remains of the Bernese guide Johannes Naegeli, missing since summer 1914, had been released by the Oberaar glacier, seventy-two years later. And so they are ever returning to us, the dead."

5. One book that made you laugh?

Anything by Charles Portis. Molloy. Parts of Tristram Shandy. Ian Frazier's stuff in a collection like Coyote v. Acme. And Dead Souls.

6. One book you wish had been written?

The book Gogol was working on after Dead Souls.

7. One book you wish had never been written?

That's a mean-spirited little question, isn't it? Oh, wait--Mein Kampf.

8. One book you are reading currently?

Twentieth-Century German Poetry: An Anthology, which FSG will publish in December. The editor, Michael Hofmann, is himself one of the best translators on the planet. And his introduction has pointed me toward some tremendous discoveries, including Gottfried Benn, whose "extraordinary, inspissated jargon-glooms" the editor considers almost translation-proof. Luckily that didn't stop Hoffman, Michael Hamburger, or Christopher Middleton from trying.

9. One book you have been meaning to read?

Middlemarch. Soon, soon!

10. Pass it on:

Let's try the formidably bookish Patrick Kurp at Anecdotal Evidence. (Whoops: Patrick already did it. Maybe I'll try Bud Parr at Chekhov's Mistress. Bud?)

1. One book that changed your life?

Oh, that's easy: Johnny Tremain by Esther Forbes, which I read when I was eight years old. Prior to that I had never really immersed myself in the imaginative world of a book--even my favorite Hardy Boys novels, like The Mystery of the Old Mill, seemed slightly ersatz. But Johnny Tremain swallowed me up. I read the second half while we were on a family vacation, and in a motel overlooking the Little Pigeon River in Tennessee, while I was pondering the molten silver that had spilled onto Johnny's hand, I walked smack into a sliding glass door. No permanent injuries.

2. One book that you have read more than once?

I've read many books more than once. A good example would be Morte D'Urban by J.F. Powers, with its quicksilver alternation of pathos and ecclesiastical comedy. On the other hand, I'm afraid I've spent nearly as much time with Hank Bordowitz's Bad Moon Rising: The Unofficial History of Creedence Clearwater Revival. Once a geek, always a geek--but clearly something about John Fogerty's crash-and-burn cycle got under my skin.

3. One book you would want on a desert island?

A long one, needless to say, so I'll choose The Divine Comedy. I'd like a version with facing text in Italian, so I could really brush up on those subjunctive constructions. Or maybe a complete Shakespeare. Or maybe Johnny Tremain.

4. One book that made you cry?

These days I'm more prone to cry when reading, as if the tears of things are always on tap. One example that comes to mind is Michael Downing's vastly underrated Perfect Agreement. Also, this passage from W.G. Sebald's The Emigrants, which I suppose will mean nothing out of context: "Three quarters of an hour later, not wanting to miss the landscape around Lake Geneva, which never fails to astound me as it opens out, I was just laying aside a Lausanne paper I'd bought in Zurich when my eye was caught by a report that said the remains of the Bernese guide Johannes Naegeli, missing since summer 1914, had been released by the Oberaar glacier, seventy-two years later. And so they are ever returning to us, the dead."

5. One book that made you laugh?

Anything by Charles Portis. Molloy. Parts of Tristram Shandy. Ian Frazier's stuff in a collection like Coyote v. Acme. And Dead Souls.

6. One book you wish had been written?

The book Gogol was working on after Dead Souls.

7. One book you wish had never been written?

That's a mean-spirited little question, isn't it? Oh, wait--Mein Kampf.

8. One book you are reading currently?

Twentieth-Century German Poetry: An Anthology, which FSG will publish in December. The editor, Michael Hofmann, is himself one of the best translators on the planet. And his introduction has pointed me toward some tremendous discoveries, including Gottfried Benn, whose "extraordinary, inspissated jargon-glooms" the editor considers almost translation-proof. Luckily that didn't stop Hoffman, Michael Hamburger, or Christopher Middleton from trying.

9. One book you have been meaning to read?

Middlemarch. Soon, soon!

10. Pass it on:

Let's try the formidably bookish Patrick Kurp at Anecdotal Evidence. (Whoops: Patrick already did it. Maybe I'll try Bud Parr at Chekhov's Mistress. Bud?)

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

What's up, Doctorow?

In last week's Chicago Tribune, Richard Stern looks at the new collection of essays by E.L. Doctorow. Stern cites the counter example of John Updike, whose voluminous reviews and occasional pieces are a key part of his output: even if you skimmed off the froth Updike always includes in his giant nonfiction collections, you'd be left with essential stuff (and in enormous quantities). For Doctorow, on the other hand, these are finger exercises, earnest and appreciative but fairly lightweight:

In last week's Chicago Tribune, Richard Stern looks at the new collection of essays by E.L. Doctorow. Stern cites the counter example of John Updike, whose voluminous reviews and occasional pieces are a key part of his output: even if you skimmed off the froth Updike always includes in his giant nonfiction collections, you'd be left with essential stuff (and in enormous quantities). For Doctorow, on the other hand, these are finger exercises, earnest and appreciative but fairly lightweight: Doctorow has no ambition to be an Updikean critic. Most of the 16 brief essays in Creationists are enjoyable, one can learn from them and perhaps also glean some insight into Doctorow's creative procedures and habits of mind, but they mostly make up the sort of brief bedtime reading one can do if one doesn't want to be so absorbed by a long book that one can't bear to put out the light.All true. However, quite aside from its nifty title, which turns the antediluvian rallying cry on its head, Creationists does boast some memorable paragraphs. Here's one, from the author's introduction, about the meaning and usefulness of fiction. Surely this subject has been done to death, no? Yet I found Doctorow's take wonderfully succinct and true:

Stories, whether written as novels or scripted as plays, are revelatory structures of facts. They connect the visible with the invisible, the present with the past. They propose life as something of moral consequence. They distribute the suffering so that it can be borne.That works for me. Bonus points: there's a Saul Steinberg drawing on the cover.

Gold digger

Yesterday, when I wasn't busy atoning, I met Kerry at the Neue Galerie for a spot of Klimt. I use the word advisedly: the top floor of the museum is currently closed for installation, which leaves only the trio of smallish rooms on the second floor. There you find five splendid Klimts--given the stiff $15 admission, that comes to three dollars per painting, or ten cents per sqaure inch of gold leaf--plus some related drawings and paintings in the adjacent rooms. The grabber (and not incidentally, the priciest painting on the planet, for which Ronald Lauder shelled out $135 million) is Adele Bloch-Bauer I. Am I dwelling on dollars too much here? Perhaps. Yet the painting itself--a Byzantine fantasia of precious metals and decorative swirls, with the subjects's all-too-human flesh suspended orchidaceously in its midst--is itself a paean to money and sex. Or so it seems to me. Bloch-Bauer's niece Maria Altmann denied any extracurricular tomfoolery between the painter and his subject, and Christopher Benfey, in the article cited above, basically compared Adele to a distracted soccer mom. Peter Schjeldahl thought otherwise--to him, this sugar magnate's wife resembles a Venus flytrap in gold lame--and so do I.

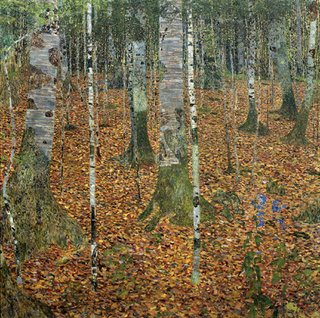

Yesterday, when I wasn't busy atoning, I met Kerry at the Neue Galerie for a spot of Klimt. I use the word advisedly: the top floor of the museum is currently closed for installation, which leaves only the trio of smallish rooms on the second floor. There you find five splendid Klimts--given the stiff $15 admission, that comes to three dollars per painting, or ten cents per sqaure inch of gold leaf--plus some related drawings and paintings in the adjacent rooms. The grabber (and not incidentally, the priciest painting on the planet, for which Ronald Lauder shelled out $135 million) is Adele Bloch-Bauer I. Am I dwelling on dollars too much here? Perhaps. Yet the painting itself--a Byzantine fantasia of precious metals and decorative swirls, with the subjects's all-too-human flesh suspended orchidaceously in its midst--is itself a paean to money and sex. Or so it seems to me. Bloch-Bauer's niece Maria Altmann denied any extracurricular tomfoolery between the painter and his subject, and Christopher Benfey, in the article cited above, basically compared Adele to a distracted soccer mom. Peter Schjeldahl thought otherwise--to him, this sugar magnate's wife resembles a Venus flytrap in gold lame--and so do I. But let's not overlook the other paintings in the room--you know, the cheap ones. Directly across from Adele Bloch-Bauer I is a scintillating (how literal that word feels when you're writing about Klimt) landscape of a birch forest. On the fatter, older birches, where the bark has peeled away, the trunks have a near-palpable gnarliness; the slender saplings dissolve into vertical stripes, and the bluebells in the right foreground look like interlopers in the Land of Decay. It's beautiful. You can't stop looking at it: what a different painter Klimt was when he checked his neuroses at the door. Nor should we shortchange the other, more casual portrait of Adele, nor the drawings in the dimly-lit room by Klimt and his naughty-boy acolyte Egon Schiele. (An anecdote from Paul Hofmann's The Viennese: Splendor, Twilight, and Exile: the youthful Schiele brought a sheaf of work to Klimt's studio and asked the older artist, "Do I have talent?" Klimt, whose brindled cat often sat on his shoulder while he worked, scanned the work and said, "Much too much.")

But let's not overlook the other paintings in the room--you know, the cheap ones. Directly across from Adele Bloch-Bauer I is a scintillating (how literal that word feels when you're writing about Klimt) landscape of a birch forest. On the fatter, older birches, where the bark has peeled away, the trunks have a near-palpable gnarliness; the slender saplings dissolve into vertical stripes, and the bluebells in the right foreground look like interlopers in the Land of Decay. It's beautiful. You can't stop looking at it: what a different painter Klimt was when he checked his neuroses at the door. Nor should we shortchange the other, more casual portrait of Adele, nor the drawings in the dimly-lit room by Klimt and his naughty-boy acolyte Egon Schiele. (An anecdote from Paul Hofmann's The Viennese: Splendor, Twilight, and Exile: the youthful Schiele brought a sheaf of work to Klimt's studio and asked the older artist, "Do I have talent?" Klimt, whose brindled cat often sat on his shoulder while he worked, scanned the work and said, "Much too much.")