Thursday, September 28, 2006

O & I

The death of Oriana Fallaci on September 15 has already prompted a string of reverential tributes and obituaries. Her lifelong habit of speaking truth to power--or sometimes shouting it at the top of her lungs--is certainly worth celebrating. So is her physical courage, which enabled her to face down bullets and burning toxins and (last but not least) Henry Kissinger in his aphrodisiacal prime. Still, Fallaci seems like an odd candidate for hagiography. She was too unruly, too explosive, to qualify for plaster sainthood. And during the final decades of her life, her ego--always at war with her sense of moral outrage--got the upper hand a little too often.

The death of Oriana Fallaci on September 15 has already prompted a string of reverential tributes and obituaries. Her lifelong habit of speaking truth to power--or sometimes shouting it at the top of her lungs--is certainly worth celebrating. So is her physical courage, which enabled her to face down bullets and burning toxins and (last but not least) Henry Kissinger in his aphrodisiacal prime. Still, Fallaci seems like an odd candidate for hagiography. She was too unruly, too explosive, to qualify for plaster sainthood. And during the final decades of her life, her ego--always at war with her sense of moral outrage--got the upper hand a little too often.A case in point would be...well, my own. In 1990 I was hired to translate Inshallah. This massive slab of a novel, which had shattered sales records in the author's native land, was set in Beirut during the fall of 1983. At that point, suicide bombers had just struck the French and American peacekeeping forces, and the Italian contingent was anxiously awaiting its turn. Oriana, who had spent some time on the ground in Beirut, seasoned her epic with plenty of blood, guts, and profanity. In fact it was the latter ingredient that got me the gig. I was younger than your average translator, and presumably more foul-mouthed, which meant that I would have less trouble with such sizzling locutions as cazzo d'un cazzo stracazzato (more on that later).

I was soon directed to a brownstone on the Upper East Side for my first meeting with the author. Oriana, who was then a spry and demonstrative 60, greeted me at the door. To the immediate left was her office, with papers and books piled on the desk and a big map of Beirut on the wall. But she motioned for me to follow her upstairs, where we sat down at a glass-topped coffee table in the living room. There were photographs and posters everywhere, including some relics of the Italian Resistance--but to be frank, you didn't study the décor when you were in Oriana's presence. You looked at her: the oval face, the pronounced cheekbones, the pale eyes, which were widely set and italicized with black eyeliner. While I sat there, jiggling my knees in awe, she gave me some pointers on tone and diction.

"James!" My name invariably had two syllables. "James, you know the writing of Hemingway?"

"I do."

"You must translate my book like him. The words must--" She made a dive-bombing hand gesture. There was some linguistic groping, and we figured out that the words were supposed to ski down the page.

I was struck by the fact that a feminist icon like Oriana would want her book to sound like a macho guy in a pith helmet. But she liked a straight shooter, and was determined in any case to make Papa look like a girly man, as I soon discovered.

"You know what cazzo is, James?"

"Of course," I said primly. "A penis."

"A dick," she corrected me. "This phrase--cazzo d'un cazzo stracazzato--I have added it to the Italian language. People use it now."

"Amazing."

She ushered me out. For the next ten months, I threw myself into the job, and from time to time we would meet for a consultation. Once she was kind enough to make me a hamburger for lunch: she ground the beef herself, not trusting the meat at the supermarket, and kept up the conversation the whole time. Was I doing any freelance work in addition to Inshallah?

"Just a little," I said.

"James, James." She shook her head. "Focus on my book. There is a big hurry."

"I won't miss my deadline."

"My good friend Sean Connery is waiting for this book. He is waiting for the translation to be in his mailbox."

While I ate the hamburger, she took a break to shout at somebody on the telephone. "Cretino!" she kept exclaiming, and I felt a stab of pity for whoever was on the other end. Luckily I seemed to be in her good graces. During a subsequent meeting, in her office on the top floor of the Rizzoli bookstore, she called somebody else a cretino on the telephone, but this time the epithet had a wearier sound to it. Her father had just died. Eating bits of some polenta-like substance from a wad of aluminum foil--her teeth were bothering her, too--she asked me to look over the English version of a memorial speech she had written for him. I was touched. She wasn't a person who relished displays of vulnerability. Might we become friends?

At this point, in early 1991, our meetings were interrupted--courtesy of Saddam Hussein, who really did belong in the jackbooted rogue's gallery that is Interview With History. Iraq had annexed Kuwait over the summer. In February the United States and its allies unleashed Operation Desert Storm, which would drive Saddam from his new protectorate in just four days. At once Oriana jetted off to Saudi Arabia, determined to dodge the Pentagon rules on pool reporting. She would get to the front or die trying--or, at least, put her Saudi guide in the hospital with heart palpitations. She did eventually get close enough to inhale fumes from the burning Kuwaiti oil wells. "The black cloud has destroyed me!" she insisted at our next meeting. The verb had three syllables. I saw her one last time, in July, and then handed in my 1,050-page translation in the fall.

At this point, in early 1991, our meetings were interrupted--courtesy of Saddam Hussein, who really did belong in the jackbooted rogue's gallery that is Interview With History. Iraq had annexed Kuwait over the summer. In February the United States and its allies unleashed Operation Desert Storm, which would drive Saddam from his new protectorate in just four days. At once Oriana jetted off to Saudi Arabia, determined to dodge the Pentagon rules on pool reporting. She would get to the front or die trying--or, at least, put her Saudi guide in the hospital with heart palpitations. She did eventually get close enough to inhale fumes from the burning Kuwaiti oil wells. "The black cloud has destroyed me!" she insisted at our next meeting. The verb had three syllables. I saw her one last time, in July, and then handed in my 1,050-page translation in the fall.Now things got sticky. As I would later learn, Oriana had already put the French translator of Inshallah through the wringer. After fiddling with his work, she had tossed it aside and substantially rewritten the novel in French. When it hit the shelves, the translation was credited to one Victor France--not the most creative pseudonym in the world.

As it turned out, she was now doing the same thing with my own manuscript, staging the equivalent of Sherman's March through nearly 300,000 words of text. The problem--aside from my wounded self-esteem--was that Oriana had a much shakier command of English than French. Her alterations, some of which I was allowed to read, were an absolute disaster. A copy editor, who deserved the Pulitzer Prize for damage control, cleaned up the worst of it. Meanwhile, the author demanded that she receive credit for the translation.

What followed were several months of ugly skirmishing. The editor at the publishing house, who was clearly scared of Oriana (who wasn't?), turned the whole matter over to the legal department. I got a lawyer of my own. There were meetings, faxes, memos fired back and forth, even a session with the president of Doubleday. Needless to say, Oriana and I never spoke again. And Inshallah, when it was finally published in 1992, was a flop. That was the only poetic justice I was granted, since the final formulation on the title page didn't exactly ring my bell: Translation by Oriana Fallaci from a translation by James Marcus. Pure nonsense. At least she didn't trot out Johnny America as a pseudonym.

All this, you might argue, is old business. Indeed it is: with the passage of time, the pain has faded and I can enjoy the comedic aspect of the whole mess. But an author who's willing to butcher her own magnum opus because can't understand how English verbs operate is something of a cretino herself. I will always admire the pugnacious conversations collected in Interview With History--nobody ever roasted a dictator over the coals with such finesse and focused rage. The two final polemics on Islam, which Oriana really did translate herself, showcase her contrarian fire (which is good) and her childish xenophobia (not so good). I’m still waiting for the memoir she was rumored to be writing in the wake of Inshallah. And despite the way she treated me, I can't help but retain a shred of affection for this impossible woman, mourning her father's death and delicately chewing on one side of her mouth. As for that black cloud--it never had a chance.

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

The green baize door

In the wake of my previous post, I began thumbing through Janet Hobhouse's Everybody Who Was Anybody: A Biography of Gertrude Stein. The author is good (and appropriately waspish) on literary maneuvering in the City of Light. In one excellent bit, it appears that Stein will abandon Ford Madox Ford's Transatlantic Review, which had been bravely serializing her work, for the tonier Criterion. She never actually jumped ship--in part because Criterion bigwig T.S. Eliot, always referred to in hushed tones as The Major, found her prose disturbing and incomprehensible. What I loved, though, was the insanely decent note Ford sent to his rising star when her departure seemed imminent:

I should be sorry to lose you, but I was never the one to stand in a contributor's way: indeed I really exist as a sort of half-way house between non-publishable youth and real money--a sort of green baize swing door that everyone kicks both on entering and leaving.

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Drama queen

Back in August, eight female poets staged a reading of Gertrude Stein's History or Messages from History, which I covered for the Poetry Foundation website. They've now posted my dispatch, complete with a splenetic title of their own devising: "Women, Gibberish and Prom Dresses." (As it happens, I'm in favor of all three.) In any case, I began this way:

You can read the rest here.The basement of Manhattan's Cornelia Street Café is a long, narrow space with colored lights dangling from the low ceiling: you feel as though you're in a root cellar with red banquettes. It certainly made for a cozy setting on August 10, when a cadre of female poets wrapped up the Finally with Women marathon with a reading of Gertrude Stein's History or Messages from History. Given the feminist tilt of the festival--which had celebrated Mina Loy, Audre Lorde, Barbara Guest, and Muriel Rukeyser on previous nights--I wondered whether many guys would be in attendance. There were a few, I'm happy to report, including one compulsive shutterbug who observed most of the proceedings through the viewfinder of his digital camera.

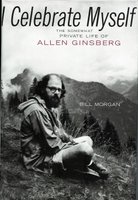

You can call me Al

Speaking of Dylan (see my previous post), I just got a copy of I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg, which details the poet's early infatuation with the Bard of Hibbing and his ambiguous role as mascot during the heyday of the Rolling Thunder Review. That aside, Bill Morgan's book is something of an oddity--surely the first biography to be transcribed directly from the subject's Filofax. I exaggerate, but only a little. Starting in the late Seventies, Morgan functioned as Ginsberg's archivist, organizing a vast chaos of papers, clippings, and photographs. It's no surprise that he would mine these materials, including the poet's journals, for his bio. Yet there's something doggedly external, even mechanical, about the finished product. Morgan tells us what Ginsberg did, year in and year out. We get a vivid sense of the quotidian--which, to be fair, is probably what the author had in mind--but very little discrimination between the momentous and the trival, as if all facts were created equal.

Speaking of Dylan (see my previous post), I just got a copy of I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg, which details the poet's early infatuation with the Bard of Hibbing and his ambiguous role as mascot during the heyday of the Rolling Thunder Review. That aside, Bill Morgan's book is something of an oddity--surely the first biography to be transcribed directly from the subject's Filofax. I exaggerate, but only a little. Starting in the late Seventies, Morgan functioned as Ginsberg's archivist, organizing a vast chaos of papers, clippings, and photographs. It's no surprise that he would mine these materials, including the poet's journals, for his bio. Yet there's something doggedly external, even mechanical, about the finished product. Morgan tells us what Ginsberg did, year in and year out. We get a vivid sense of the quotidian--which, to be fair, is probably what the author had in mind--but very little discrimination between the momentous and the trival, as if all facts were created equal.One thing that does emerge from Morgan's book is Ginsberg's strange mixture of grandiosity and Zen-flavored self-effacement. Only days prior to his death, this prophetic personality was still hitting up the White House for the artistic equivalent of the Good Conduct Medal (no doubt he was the last person to treat Bill Clinton as a father figure). The anecdote is so representative that Morgan tells it twice, but here's the more detailed version:

One afternoon before he left the hospital he drafted a letter to President Clinton and asked Hale to type it. The short letter told the president, "I have untreatable liver cancer and have 2-5 months to live. If you have some sort of award or medal for service in art or poetry, please send one along unless it's politically inadvisable or inexpedient. I don't want to bait the right wing for you. Maybe Gingrich might or might not mind. But don't take chances please, you've enough on hand." After a lifetime of enjoying such great success and worldwide fame in writing poetry it was bittersweet that Allen felt he needed a final pat on the back from someone like the president. That night in the hospital bathroom, Allen looked in the mirror and said out loud, "Stop scheming, Ginsberg," thinking of that letter. However, when the draft was typed the next day, he signed it and had it mailed to the White House anyway. His own line, "Don't follow my path to extinction," had never been more appropriate.Sad, fascinating, funny. The passage gives a good sample of Morgan's style, which might charitably be called Buddhist meat-and-potatoes, and an atypical (i.e., judgmental) closing sentence. Incidentally, no reply came from the White House. Ginsberg died at home, at 2:30 in the morning, on April 5, 1997. His last recorded words appear to have been: "Gee, I never did that before."

In a thoughtful piece in the new Bookforum, John Palattella discusses the Morgan bio and the fiftieth-anniversary valentines (there were quite a few) addressed to Howl. He too finds I Celebrate Myself a little too mild-mannered in tone, especially when it comes to the more iffy episodes in Ginsberg's life. (Example: the ease with which the poet forgave his guru, Chögyam Trungpa, after the thin-skinned master had W.H. Merwin and his girlfriend stripped and paraded around his Halloween party. Click here for an excellent summary of the so-called Naropa Affair.) Palattella also addresses the diminishing quality of the poetry itself, and chalks up this decline to the gradual encroachment of Ginsberg's persona--the wild and whacky shaman--upon his art.

Perhaps the central mystery of Ginsberg's career is why he published so much work he knew wasn't up to snuff. Morgan says that Ginsberg thought many of the poems in Planet News, 1961–1967, which appeared in 1968, were drivel but that he chose to include them in the book nevertheless. Ginsberg admired the poetry of Basil Bunting, especially Briggflatts, but he didn't share Bunting's affection for the wastepaper basket or the blue pencil. ("Howl," which was heavily revised, is an exception.) Was Ginsberg's work blighted by the poet gradually becoming a prisoner of what Morgan calls "the business of being Allen Ginsberg," with the constant travel from one reading or meeting or protest to another making his desk into another foreign destination? Whatever the answer, the sad truth is that Ginsberg, through his failure to create a body of work that wasn't merely derivative of his greatest hits--which are truly great--did end up sharing the fate of many a rock star.Finally: if you can't beat 'em, join 'em. Here's a late collaboration between Ginsberg and an actual rock star, Sir Paul McCartney. The freaky imagery and Sixties footage come courtesy of director Gus Van Sant, and the poet, wearing a stovepipe hat in the opening shots, looks like he's playing Abe Lincoln in a school pageant. Not the greatest poetry, but hey, that's entertainment.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

Silence, please

Since I'm about to run out the door (out of which I should have run at least 30 minutes ago), I'll confine myself to sharing this brief poem by Marianne Moore. "Silence" is an early piece, originally issued in Poems (1924)--which is to say, long before she got lost in the syllabic thickets of her late manner. (Click here for some handy footnotes. And a tip of the hat to Kerry F. for pointing out the poem in the first place.)

My father used to say,

"Superior people never make long visits,

have to be shown Longfellow's grave

or the glass flowers at Harvard.

Self-reliant like the cat--

that takes its prey to privacy,

the mouse's limp tail hanging like a shoelace from its mouth--

they sometimes enjoy solitude,

and can be robbed of speech

by speech which has delighted them.

The deepest feeling always shows itself in silence;

not in silence, but restraint."

Nor was he insincere in saying, "Make my house your inn."

Inns are not residences.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

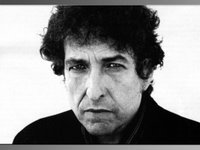

re: Bob

For most writers, stalling is not only an occupational hazard but a fine art. So when I breezed into the Merc on Friday for a long afternoon of translating, the first thing I did was find a way not to work: I picked up Jonathan Lethem's Rolling Stone interview with Bob Dylan. I knew I had made the right decision the moment I came across Dylan's comment about the joys of literary composition. "That's what I like about books," he noted, "there's no noise in it." Even better was his artistic credo, delivered right at the end of the piece, which puts the individual, the utter eccentric, up on the pedestal where he or she belongs:

For most writers, stalling is not only an occupational hazard but a fine art. So when I breezed into the Merc on Friday for a long afternoon of translating, the first thing I did was find a way not to work: I picked up Jonathan Lethem's Rolling Stone interview with Bob Dylan. I knew I had made the right decision the moment I came across Dylan's comment about the joys of literary composition. "That's what I like about books," he noted, "there's no noise in it." Even better was his artistic credo, delivered right at the end of the piece, which puts the individual, the utter eccentric, up on the pedestal where he or she belongs:That was what you heard--the individual crying in the wilderness. So that's kind of lost too. I mean, who's the last individual performer that you can think of--Elton John, maybe? I'm talking about artists with the willpower not to conform to anybody's reality but their own. Patsy Cline and Billy Lee Riley. Plato and Socrates, Whitman and Emerson. Slim Harpo and Donald Trump. It's a lost art form. I don't know who else does it beside myself, to tell you the truth.Now, one of these things (as the song goes) is not the like the other ones. Still, Bob is dead serious, and correct, about the mulish, contrarian power of the real Prometheans. Yes, it's a tiny club. And yes, Bob appears to be a member in good standing, having just released his third firecracker in a row. Like Love and Theft, the self-produced treasures on Modern Times split the difference between nasty blues and Dylan's oddly endearing croon. Jody Rosen's excellent piece at Slate covered most of the bases, although I would differ with him on two points. First, Modern Times hasn't yet nosed out its predecessor, at least not to my ear--there's nothing on the new disc with quite the damn-the-torpedoes intensity of "Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum." But Rosen also illustrates the peril of subtracting the words from the music, at least in his discussion of "Beyond the Horizon." Rosen calls it

one of the most starry-eyed Dylan has ever sung, a gently tumbling soft-shoe that takes a celestial view of romance: "Beyond the horizon/ In springtime or fall/ Love waits forever/ For one and for all." The lines vaguely recall Philip Larkin's famous "what will survive of us is love," and for all the blues-drenched premonitions of doom and rambling bad-ass tales on Modern Times, I suspect that love is the thing that will survive of it.He's right about the disc's sweet disposition but wrong, surely, about the quality of those lines, which fall well short of Philip Larkin and wouldn't be out of place on a Hallmark greeting card. Dylan can get away with this stuff because of the cryptic, comedic, heartbreaking language that surrounds it, and because his performance fills in the blanks spots and then some. When the poet falters, in other words, the singer picks up the slack.

It was ever thus, argues Gary Giddins, in a piece from his splendid new collection Natural Selection. In "Who's Gonna Throw That Minstrel Boy a Coin?", Giddins is quick to acknowledge his subject's verbal wizardry as "a phrasemaker unrivaled since Johnny Mercer, if not Kipling." But what really interests him is Dylan's stature as a singer, whose theatrical, protean attack more than compensated for his technical limitations:

It was ever thus, argues Gary Giddins, in a piece from his splendid new collection Natural Selection. In "Who's Gonna Throw That Minstrel Boy a Coin?", Giddins is quick to acknowledge his subject's verbal wizardry as "a phrasemaker unrivaled since Johnny Mercer, if not Kipling." But what really interests him is Dylan's stature as a singer, whose theatrical, protean attack more than compensated for his technical limitations:In the '60s, his singing was often found so repellent that his admirers readily apologized for it. Forget the voice, they said, listen to the words--an argument that found its logical outcome as well as box-office support in covers by Peter, Paul and Mary and the Byrds. Yet it was Dylan's unmistakable anti-stylish stylish singing that made him irresistible and unique to those very admirers. His singing was so original that they praised it chiefly for what it wasn't: smooth, which is to say commercial. Approbation, such as it was, centered on his rough-hewn timbre, Woody-like naturalness, road-tested coarseness, conversational ease. Detractors who claimed that he was unintelligible simply were not listening--Dylan's early elocution was crystal. They were too much put off by the snarling, chortling, demonic voice that implied "fuck you" even while insisting, "All I really want to do is, baby, be friends with you."Exactly. The book, by the way, is heavily tilted toward film criticism, which Giddins has practiced at the New York Sun ever since the Voice was dumb enough to show him the door. Believe it or not, he's as eloquent and encyclopedically informed about movies as he is about jazz and popular music. Give him his Pulitzer, please--it's at least twenty years overdue.

Thursday, September 07, 2006

Meetings with remarkable men (and their wives)

In the current Atlantic Monthly, Christopher Hitchens roasts JFK and his legacy over some white-hot coals. It's been a long time, of course, since anybody took the myth of Camelot at face value. With his playground notion of foreign policy and a compulsive sexual appetite that makes Clinton look like a 40-year-old virgin, Kennedy seems less and less like a candidate for Mount Rushmore. In any case, Hitchens's rhetorical blast came to mind the other day when I read an excerpt from Aaron Copland's diary, in which he describes the White House gala he attended on November 13, 1961. The evening honored Pablo Casals. Note Copland's patriotic pique at the omission of American music from the program:

I sat between Mrs. Walter Lippman and Mrs. William Paley. Pierre Salinger and Senator Mike Mansfield were at our table. President Kennedy was in full view the entire time, while ten violins played through dinner. Surprised at his reddish-brown hair. No evil in the face, but plenty of ambition there, no doubt. Mrs. K. statuesque. A ceremonial entry with the presentation of colors preceded dinner at which guests were presented to President and Mrs. Kennedy. Seemed to note a glance of recognition from Mr. and Mrs. Kennedy. After dinner we were treated to a concert by Pablo Casals. No American music. The next step.

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

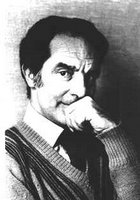

Calvino's death

By now I've made a habit out of picking up and putting down Harry Mathews's The Case of the Persevering Maltese: Collected Essays. I'm drawn to the guy's obvious intelligence and elan, but I have a limited appetite for Oulipian shenanigans. Still, the other day I read "La Camera Ardente," about Italo Calvino, and found it tremendously touching. A camera ardente is a large room at the hospital in which the deceased is laid out for public viewing. Here is Mathews:

By now I've made a habit out of picking up and putting down Harry Mathews's The Case of the Persevering Maltese: Collected Essays. I'm drawn to the guy's obvious intelligence and elan, but I have a limited appetite for Oulipian shenanigans. Still, the other day I read "La Camera Ardente," about Italo Calvino, and found it tremendously touching. A camera ardente is a large room at the hospital in which the deceased is laid out for public viewing. Here is Mathews:The hall--the sala d'infermeria or pellegrinaio, covered with lofty frescoes by Domenico di Bartolo depicting scenes full of elegantly striped and stockinged personages--occupied so vast a cubic space that it made little difference whether one was alone in it or among fifty fellow mourners. Calvino had been laid out near its windows in an asymmetically hexagonal coffin, under a pleated white satin coverlet that made him look child-size. Emerging from the coverlet, his head showed the effects of his operation: the right side shaven, a ridge running front to back over the cranium where the bone had been cut; such details only underlined the inevitably appalling disparity between a face known alive and the same face dead. Many men and women stepped up to the coffin, afterwards departing or joining those of us sitting or standing along the sides of the hall. A group of eleven-year-old boys was ushered in by a schoolteacher. I thought, why expose them to such a sight? But many, as they left, were weeping tears of unmistakable grief, and I was told that these were readers of Marcovaldo: they were mourning the creator of a book that they loved.The precision of this passage--its cool notation of the room, the coffin, the coverlet, and the "appalling disparity" between life and death--is surely something Calvino himself would have appreciated. I was also struck by the sobbing children. I don't want to idealize the literary culture of Italy, where most people on the train seem to be reading fumetti or translations of The Da Vinci Code. Yet I can't imagine any American writer inspiring such a display of grief among the preteen demographic.

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Two books

On Sunday the Los Angeles Times Book Review ran my piece on Jonathan Franzen's The Discomfort Zone. This slender collection of five autobiographical essays has already come in for some moderate drubbing, most notably from the tin-eared Michiko Kakutani, who reviewed the author's persona instead of his book. Granted, the youthful Franzen often comes off as a real prat. But with one exception--the chapter on the author's teenage pranks--he seems very much aware of how callow and crude he was, and determined not to pretty up his adolescent angst with post-production trickery. Good for him. I began this way:

In one chapter of his new memoir, Jonathan Franzen recalls his youthful immersion in the German language, which culminated in a grudging conquest of The Magic Mountain. It was, appropriately, an uphill battle. Thomas Mann's masterwork, with its jackhammer ironies and its Teutonic nerd of a protagonist, almost drove the Swarthmore senior out of his mind. Yet he recognized "at the heart of the book...a question of genuine personal interest both to Mann and to me: How does it happen that a young person so quickly strays so far from the values and expectations of his middle-class upbringing?"You can read the rest here. Meanwhile, I also reviewed Peter Behrens's The Law of Dreams for Newsday. This first novel got off to a shakey start--the opening paragraph was a virtual compendium of Hibernian cliches, complete with Farmer Carmichael riding "his old red mare Sally through the wreck of Ireland"--but what followed was weirdly captivating:

As readers will discover, that's also the question at the heart of The Discomfort Zone: A Personal History. Since Franzen is a superlative novelist rather than a sociologist, he approaches the question from some fairly oblique angles. But wrestle with it he does, beginning with the very first chapter, "House for Sale." The year is 1999, and Franzen, still many moons away from the matinee-idol status he attained in 2001 with his bestselling third novel, The Corrections, has journeyed to Webster Groves, Mo. There, in the wake of his mother's death, he has been charged with selling his boyhood home.

In an early poem, one still draped in the gauzy cadences of the Celtic Twilight, W.B. Yeats invoked the "great wind of love and hate." No doubt this chaotic breeze was meant to blow throughout the entire world. Yet there seems something specifically Irish about its intensity and destructive impact. Certainly it whips through the pages of The Law of Dreams, applying its invisible force to both the hero and to "the wreck of Ireland" itself.Stay tuned for further posts about The Mystery Guest, Calvino, Aaron Copland, the Who, James Schuyler's letters to Frank O'Hara, and my unhealthy new fixation on Beatles bootlegs.

The latter phrase can only be called an understatement. When Peter Behrens's first novel opens, in 1846, Ireland is in the lethal grip of the Great Famine. Starvation and typhus would kill more than 500,000 during the next five years and turn millions into refugees.

The protagonist, a country bumpkin named Fergus, hasn't yet grasped the impending catastrophe. Then the potato blight hits the hilly precincts where his family has long scratched out a living as tenant farmers. In a matter of months, his mother, father and siblings are dead, his home is burned to the ground, and Fergus, expelled by the landlord, is left with nothing but "the ancestral glow of tedious, unilluminating anger."

Thus begins his journey though the landscape of disaster. "Walk outside," he tells himself. "That is what you do in dreams. The law of dreams is, keep moving." And move he does, from the filthy enclosure of the Scariff Workhouse to a dreamlike interval out on the bogs. There he joins a marauding band of adolescents and loses his virginity to their chieftan (who only seems to be a boy).

This is, to put it mildly, a happy event. It also highlights one of the great strengths of the book: its resistance to easy sentiment, always a danger in a historical novel, where we tend to assume that self-consciousness is a modern invention. Fergus is delighted by sex, by intimacy. Yet he sees his own isolation for what it is: "It was strange how you connected with a girl, violence mixed with peculiar tenderness. And you thought you were deep inside, but you weren't. No one was. Other people, machines of independent mystery."

On and on he goes, both drawn to and repelled by "the unyielding, metallic otherness of the world." When the band dissolves--in a bloody shootout that the author handles like a soft-focus Peckinpah--Fergus crosses the water to Liverpool. He has escaped the wreck of Ireland. However, his adventures in the metropolis, drawn with fantastic, sooty precision by the author, are hardly less bizarre. The proprietress of an Irish bordello takes him in, restores his health, and prepares him for a career as a male prostitute. A shaken Fergus hits the road again, working on a railroad construction crew in Wales. Only then, having acquired a small pile of cash and a de facto wife, does he embark for his final destination: America.

Fergus's Atlantic crossing is one of the great set pieces in The Law of Dreams, all the more remarkable because we've seen it before, in almost every chronicle of the Irish diaspora. Behrens spares nothing when it comes to the dread and discomfort of the passage. At the same time, the details of shipboard life--say, a sailor high in the rigging--strike Fergus as portents of liberation: "He'd rather be living up there, in the high, than down below in the hold. All his life he had lived in holes of one sort or another: cabins made of stones and turf; scalpeens made of sticks, shanties, steerage holds. Burrows smelling of earth and bodies."

Will America offer him an escape from this burrow, which is also the downward tug of death and memory? Will the New World transform him? The answer is twofold. Fergus does lose his innocence, what little there is left of it. For a dizzying moment his very appetite for experience seems on the verge of disappearing: "I have eaten too much the world. I am not hungry no more." In the end, though, the law of dreams will not relinquish him. He must keep moving.

Happily this mandate of eternal motion applies to the author as well. He never lets his story go slack, never lets it eddy on the margins for more than a page or two. Then Fergus is carried along once again. This is not a matter of streamlined minimalism: no, Behrens has fashioned a beautiful idiom for his book, studded with slippery archaisms and mournful, musical refrains. Here and there he hits a pothole, a muddy patch. For the most part, though, the language and the things it describes seem to be spun out of a single material. And we move through it as willingly, or compulsively, as the protagonist, the wind of love and hate at our backs.