Thursday, April 27, 2006

Martin A. and Patrick M.

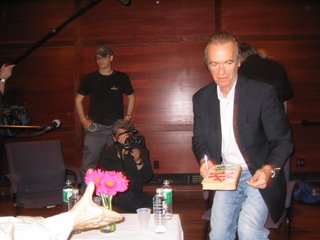

Martin Amis and Patrick McGrath, who appeared at Hunter College this afternoon as part of the PEN World Voices Festival, make an interesting pair. Amis is slight, voluble, his pale hair combed straight back as if he were perpetually facing into a brisk wind. McGrath is bigger, more stout, and as they spoke he tended to bring up the rear. After a brief intro by Salman Rushdie--who's apparently being beamed from one event to another via some sort of Star Trek teleportation device--the two authors quickly took their seats and got down to business.

Initially they continued a conversation that had begun the night before, in the wake of the exhaustive (and, some say, exhausting) Faith and Reason marathon at Town Hall. The various testimonies onstage, Amis said, had convinced him that the quintessential "human quality was doubt rather than passionate commitment." Yet he was unwilling to pull the plug on the entire enterprise of belief. "I do not call myself an atheist," he added. "That would be a little crabbed and immature."

McGrath fired back: "Even if you're an agnostic, doesn't it make sense to do what Pascal said, or did?" Which is to say: hedge one's bets by praying. Amis was unmoved. He fired off an epigrammatic blast of his own: "If God had really cared about us--if he really loved us--he would never have given us religion." Now, however, things got more interesting, as the two non-believers relinquished their game of verbal pingpong and took up the matter of Muhammad Atta, who served as the subject of a recent story by Amis in The New Yorker. (Ironically, Amis suggests that Atta wasn't a believer, either, just a hideous nihilist with a competitive streak.)

From there they moved on to Iran. Amis, who wrote a great deal about the nightmare of nuclear weaponry during the 1980s, insisted that such devices be kept out of Iranian hands. "Sorry," he said. "They just can't have them!" McGrath quite reasonably asked how this was to be accomplished. "By swearing them off yourselves," Amis replied. Not likely, is it? Especially as the current administration announces plans to rebuild existing weapons facilities and commission new bomb designs. But we can always hope.

Meanwhile, after touching on Amis's novel Yellow Dog, head trauma, Abu Gharib, and extraordinary rendition, the conversation drifted back to suicide bombing (which Amis prefers to call "suicide mass murder.") The practice, he argued, is not simply war by other means, but a repellent Islamist specialty, degrading in every possible way. "It makes a human being regard another human being with a brand new level of disgust and revulsion," he insisted.

There followed a brief Q-and-A session. One member of the audience cited a comment made the previous night by the Brazilian novelist Milton Hatoum: "We are living in hopeless times." Was it so? "Look," Amis replied, "all times look hopeless. The Nineties, for example, were a kind of Golden Age. We had so much time on our hands that we could devote an entire year to Monica Lewinsky, an entire year to O.J. Simpson." And yet suddenly, as of 2001, we were plunged into battle with a terrible, supremely irrational enemy. "Hopeless times," echoed McGrath, without indicating whether he accepted the diagnosis or was simply taking the phrase for a spin. But now the clock had run out, and both authors retreated toward the back of the stage, surrounded by a praetorian guard of cameras and boom microphones. Amis gamely signed a few autographs, too, at which point I snapped the action photo above.

There followed a brief Q-and-A session. One member of the audience cited a comment made the previous night by the Brazilian novelist Milton Hatoum: "We are living in hopeless times." Was it so? "Look," Amis replied, "all times look hopeless. The Nineties, for example, were a kind of Golden Age. We had so much time on our hands that we could devote an entire year to Monica Lewinsky, an entire year to O.J. Simpson." And yet suddenly, as of 2001, we were plunged into battle with a terrible, supremely irrational enemy. "Hopeless times," echoed McGrath, without indicating whether he accepted the diagnosis or was simply taking the phrase for a spin. But now the clock had run out, and both authors retreated toward the back of the stage, surrounded by a praetorian guard of cameras and boom microphones. Amis gamely signed a few autographs, too, at which point I snapped the action photo above.

Initially they continued a conversation that had begun the night before, in the wake of the exhaustive (and, some say, exhausting) Faith and Reason marathon at Town Hall. The various testimonies onstage, Amis said, had convinced him that the quintessential "human quality was doubt rather than passionate commitment." Yet he was unwilling to pull the plug on the entire enterprise of belief. "I do not call myself an atheist," he added. "That would be a little crabbed and immature."

McGrath fired back: "Even if you're an agnostic, doesn't it make sense to do what Pascal said, or did?" Which is to say: hedge one's bets by praying. Amis was unmoved. He fired off an epigrammatic blast of his own: "If God had really cared about us--if he really loved us--he would never have given us religion." Now, however, things got more interesting, as the two non-believers relinquished their game of verbal pingpong and took up the matter of Muhammad Atta, who served as the subject of a recent story by Amis in The New Yorker. (Ironically, Amis suggests that Atta wasn't a believer, either, just a hideous nihilist with a competitive streak.)

From there they moved on to Iran. Amis, who wrote a great deal about the nightmare of nuclear weaponry during the 1980s, insisted that such devices be kept out of Iranian hands. "Sorry," he said. "They just can't have them!" McGrath quite reasonably asked how this was to be accomplished. "By swearing them off yourselves," Amis replied. Not likely, is it? Especially as the current administration announces plans to rebuild existing weapons facilities and commission new bomb designs. But we can always hope.

Meanwhile, after touching on Amis's novel Yellow Dog, head trauma, Abu Gharib, and extraordinary rendition, the conversation drifted back to suicide bombing (which Amis prefers to call "suicide mass murder.") The practice, he argued, is not simply war by other means, but a repellent Islamist specialty, degrading in every possible way. "It makes a human being regard another human being with a brand new level of disgust and revulsion," he insisted.

There followed a brief Q-and-A session. One member of the audience cited a comment made the previous night by the Brazilian novelist Milton Hatoum: "We are living in hopeless times." Was it so? "Look," Amis replied, "all times look hopeless. The Nineties, for example, were a kind of Golden Age. We had so much time on our hands that we could devote an entire year to Monica Lewinsky, an entire year to O.J. Simpson." And yet suddenly, as of 2001, we were plunged into battle with a terrible, supremely irrational enemy. "Hopeless times," echoed McGrath, without indicating whether he accepted the diagnosis or was simply taking the phrase for a spin. But now the clock had run out, and both authors retreated toward the back of the stage, surrounded by a praetorian guard of cameras and boom microphones. Amis gamely signed a few autographs, too, at which point I snapped the action photo above.

There followed a brief Q-and-A session. One member of the audience cited a comment made the previous night by the Brazilian novelist Milton Hatoum: "We are living in hopeless times." Was it so? "Look," Amis replied, "all times look hopeless. The Nineties, for example, were a kind of Golden Age. We had so much time on our hands that we could devote an entire year to Monica Lewinsky, an entire year to O.J. Simpson." And yet suddenly, as of 2001, we were plunged into battle with a terrible, supremely irrational enemy. "Hopeless times," echoed McGrath, without indicating whether he accepted the diagnosis or was simply taking the phrase for a spin. But now the clock had run out, and both authors retreated toward the back of the stage, surrounded by a praetorian guard of cameras and boom microphones. Amis gamely signed a few autographs, too, at which point I snapped the action photo above.Wednesday, April 26, 2006

Pamuk at PEN

Literature, as we all know, is supposed to be ailing. Some might even call it moribund. But to judge from the crowd last night at Cooper Union, which snaked completely around the block in a light drizzle, reports of its death have been highly exaggerated. This legion of bibliophiles had turned out to see Orhan Pamuk deliver the first Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Lecture. The Turkish novelist was, of course, an ideal speaker for the occasion, having just dodged a jail sentence for publicly rattling some of the skeletons in his own nation’s closet. Yet the atmosphere in the Great Hall at Cooper Union was far from sober. There were cameras everywhere, and a sort of fizzy anticipation more typical of American Idol than your average PEN event. Indeed, when the three stars of the evening--Pamuk, Margaret Atwood, and Salman Rushdie--entered from stage right, I almost expected them to burst into a Supremes medley, so rapturous was the applause.

Rushdie kicked off the evening (and the PEN World Voices Festival) with a few words of welcome. From where I sat, he was perfectly eclipsed by one of the hall's structural columns. Yet his disembodied voice adverted first to the late Arthur Miller, then to the awards his fellow authors had won. "Orhan is the winner of the heaviest award in the world," he told the capacity crowd. "The IMPAC. You can kill somebody with it." Atwood, on the other hand, had bagged the coveted Swedish Humor Award. (No doubt Rushdie will be picketed for that one, if not actually pelted with dried herring.) On a more serious note, he expressed his hope that the festival "would reopen the dialogue between America and the rest of the world," and turned the podium over to Pamuk.

Rushdie kicked off the evening (and the PEN World Voices Festival) with a few words of welcome. From where I sat, he was perfectly eclipsed by one of the hall's structural columns. Yet his disembodied voice adverted first to the late Arthur Miller, then to the awards his fellow authors had won. "Orhan is the winner of the heaviest award in the world," he told the capacity crowd. "The IMPAC. You can kill somebody with it." Atwood, on the other hand, had bagged the coveted Swedish Humor Award. (No doubt Rushdie will be picketed for that one, if not actually pelted with dried herring.) On a more serious note, he expressed his hope that the festival "would reopen the dialogue between America and the rest of the world," and turned the podium over to Pamuk.

Given the diffident tone of his prose, I was eager to hear what Pamuk sounded like. His voice was light but assertive, with a Turkish accent and an audible relish for paradox. What he discussed, first of all, were the dark days of 1980, when a bloodless coup by the Turkish military made a hash of civil liberties throughout the country. On that occasion Harold Pinter and Arthur Miller flew into Istanbul as a gesture of solidarity with Turkey's persecuted writers--and their guide, selected for his fluent English, was a young novelist named Orhan Pamuk.

Even then, Pamuk had mixed feelings about this descent into the political trenches: "I felt an equal and opposite desire to protect myself from all this, to do nothing in life but write beautiful novels." He also noted the sad fact that many of the victims of government persecution have managed, a generation later, to turn the tables. "Twenty years on," he said, "half of these same people align themselves with nationalism." Still, he defended freedom of expression as a human necessity--and advised authors not to muzzle their characters, either, in the interest of political correctness. "I am the kind of novelist who makes it his business to identify with all his characters," he insisted. "Especially the bad ones."

This was, perhaps, preaching to the choir. Still, it was a lively sermon. And Pamuk wrapped it up by denouncing the debacle in Iraq, which "has brought neither peace nor democracy" to the region. "This savage and cruel war is the shame of America and the West," he argued. "It is PEN, and writers like Arthur Miller, who are its pride." No mincing words there. The audience rose to its feet, and Pamuk now adjourned to a table in the center of the stage for his conversation with Margaret Atwood.

Dressed, like Pamuk, in basic black--they looked like a pair of undertakers--Atwood settled into her chair and removed a list of questions from her tote bag. She began by asking him about the intertwined roles of shame and pride in his fiction. "It is very productive," he replied, "for a novelist to carry around two different ideas." There is, Pamuk added, "a constant civil war in each person's head," and a good novelist inevitably fights for both sides at once. The reader, conversely, should take no side at all. Instead Pamuk prefers to immerse his audience in a productive state of confusion--or, as he calls it, "the entire galaxy of situations."

Dressed, like Pamuk, in basic black--they looked like a pair of undertakers--Atwood settled into her chair and removed a list of questions from her tote bag. She began by asking him about the intertwined roles of shame and pride in his fiction. "It is very productive," he replied, "for a novelist to carry around two different ideas." There is, Pamuk added, "a constant civil war in each person's head," and a good novelist inevitably fights for both sides at once. The reader, conversely, should take no side at all. Instead Pamuk prefers to immerse his audience in a productive state of confusion--or, as he calls it, "the entire galaxy of situations."

Next Atwood asked him about the act of composition. What happens when he sits down to write? "The world of telephones and gas bills, the usual tedious details of life, disappear," Pamuk replied. "Leaf by leaf, street by street, window by window, I make a whole new world, in which I feel much more secure than in the world of gas bills and tedium." This sounded like the most glowing endorsement of escapism since J.M. Barrie cranked out Peter Pan. Yet a few minutes later, Pamuk summed up his creative process in more pharmaceutical terms: "I have to be alone every day, and take this pill of the imagination." At that point every novelist in the crowd was doubtless asking the same, envious question: is this pill available over the counter?

Now Atwood moved on to the question of vocation, which Pamuk treated at length in his most recent book, Istanbul: Memories and the City. At Cooper Union, he was more concise: "Bookish boys in my part of the world want to be poets. You have to write bad poetry in order to become a good novelist." But hadn't he, as Atwood put it, undertaken his literary career in order to "write Turkey into being?" Pamuk, who seems like a genuinely modest man, batted away any such grandiosity. "I have described the adventures of my nation in various ways," was all he would say, without acknowledging that you could apply the very same formula to Leaves of Grass or The Divine Comedy.

Now Atwood moved on to the question of vocation, which Pamuk treated at length in his most recent book, Istanbul: Memories and the City. At Cooper Union, he was more concise: "Bookish boys in my part of the world want to be poets. You have to write bad poetry in order to become a good novelist." But hadn't he, as Atwood put it, undertaken his literary career in order to "write Turkey into being?" Pamuk, who seems like a genuinely modest man, batted away any such grandiosity. "I have described the adventures of my nation in various ways," was all he would say, without acknowledging that you could apply the very same formula to Leaves of Grass or The Divine Comedy.

As an interlocutor, Atwood was perfectly okay. At times I wondered whether Rushdie himself--no novice when it comes to fictional explorations of shame and pride--might have been more in synch with Pamuk, more able to tease out what makes him so distinctive. Yet there was one moment that seemed to comically encapsulate Pamuk's tone, with its murmuring disclosures and meaningful silences. "I'm going ask you a personal question," Atwood said, "but you don't have to answer it." The guest of honor paused. Then he replied: "Okay. If I answer, you don't have to listen."

Rushdie kicked off the evening (and the PEN World Voices Festival) with a few words of welcome. From where I sat, he was perfectly eclipsed by one of the hall's structural columns. Yet his disembodied voice adverted first to the late Arthur Miller, then to the awards his fellow authors had won. "Orhan is the winner of the heaviest award in the world," he told the capacity crowd. "The IMPAC. You can kill somebody with it." Atwood, on the other hand, had bagged the coveted Swedish Humor Award. (No doubt Rushdie will be picketed for that one, if not actually pelted with dried herring.) On a more serious note, he expressed his hope that the festival "would reopen the dialogue between America and the rest of the world," and turned the podium over to Pamuk.

Rushdie kicked off the evening (and the PEN World Voices Festival) with a few words of welcome. From where I sat, he was perfectly eclipsed by one of the hall's structural columns. Yet his disembodied voice adverted first to the late Arthur Miller, then to the awards his fellow authors had won. "Orhan is the winner of the heaviest award in the world," he told the capacity crowd. "The IMPAC. You can kill somebody with it." Atwood, on the other hand, had bagged the coveted Swedish Humor Award. (No doubt Rushdie will be picketed for that one, if not actually pelted with dried herring.) On a more serious note, he expressed his hope that the festival "would reopen the dialogue between America and the rest of the world," and turned the podium over to Pamuk. Given the diffident tone of his prose, I was eager to hear what Pamuk sounded like. His voice was light but assertive, with a Turkish accent and an audible relish for paradox. What he discussed, first of all, were the dark days of 1980, when a bloodless coup by the Turkish military made a hash of civil liberties throughout the country. On that occasion Harold Pinter and Arthur Miller flew into Istanbul as a gesture of solidarity with Turkey's persecuted writers--and their guide, selected for his fluent English, was a young novelist named Orhan Pamuk.

Even then, Pamuk had mixed feelings about this descent into the political trenches: "I felt an equal and opposite desire to protect myself from all this, to do nothing in life but write beautiful novels." He also noted the sad fact that many of the victims of government persecution have managed, a generation later, to turn the tables. "Twenty years on," he said, "half of these same people align themselves with nationalism." Still, he defended freedom of expression as a human necessity--and advised authors not to muzzle their characters, either, in the interest of political correctness. "I am the kind of novelist who makes it his business to identify with all his characters," he insisted. "Especially the bad ones."

This was, perhaps, preaching to the choir. Still, it was a lively sermon. And Pamuk wrapped it up by denouncing the debacle in Iraq, which "has brought neither peace nor democracy" to the region. "This savage and cruel war is the shame of America and the West," he argued. "It is PEN, and writers like Arthur Miller, who are its pride." No mincing words there. The audience rose to its feet, and Pamuk now adjourned to a table in the center of the stage for his conversation with Margaret Atwood.

Dressed, like Pamuk, in basic black--they looked like a pair of undertakers--Atwood settled into her chair and removed a list of questions from her tote bag. She began by asking him about the intertwined roles of shame and pride in his fiction. "It is very productive," he replied, "for a novelist to carry around two different ideas." There is, Pamuk added, "a constant civil war in each person's head," and a good novelist inevitably fights for both sides at once. The reader, conversely, should take no side at all. Instead Pamuk prefers to immerse his audience in a productive state of confusion--or, as he calls it, "the entire galaxy of situations."

Dressed, like Pamuk, in basic black--they looked like a pair of undertakers--Atwood settled into her chair and removed a list of questions from her tote bag. She began by asking him about the intertwined roles of shame and pride in his fiction. "It is very productive," he replied, "for a novelist to carry around two different ideas." There is, Pamuk added, "a constant civil war in each person's head," and a good novelist inevitably fights for both sides at once. The reader, conversely, should take no side at all. Instead Pamuk prefers to immerse his audience in a productive state of confusion--or, as he calls it, "the entire galaxy of situations."Next Atwood asked him about the act of composition. What happens when he sits down to write? "The world of telephones and gas bills, the usual tedious details of life, disappear," Pamuk replied. "Leaf by leaf, street by street, window by window, I make a whole new world, in which I feel much more secure than in the world of gas bills and tedium." This sounded like the most glowing endorsement of escapism since J.M. Barrie cranked out Peter Pan. Yet a few minutes later, Pamuk summed up his creative process in more pharmaceutical terms: "I have to be alone every day, and take this pill of the imagination." At that point every novelist in the crowd was doubtless asking the same, envious question: is this pill available over the counter?

Now Atwood moved on to the question of vocation, which Pamuk treated at length in his most recent book, Istanbul: Memories and the City. At Cooper Union, he was more concise: "Bookish boys in my part of the world want to be poets. You have to write bad poetry in order to become a good novelist." But hadn't he, as Atwood put it, undertaken his literary career in order to "write Turkey into being?" Pamuk, who seems like a genuinely modest man, batted away any such grandiosity. "I have described the adventures of my nation in various ways," was all he would say, without acknowledging that you could apply the very same formula to Leaves of Grass or The Divine Comedy.

Now Atwood moved on to the question of vocation, which Pamuk treated at length in his most recent book, Istanbul: Memories and the City. At Cooper Union, he was more concise: "Bookish boys in my part of the world want to be poets. You have to write bad poetry in order to become a good novelist." But hadn't he, as Atwood put it, undertaken his literary career in order to "write Turkey into being?" Pamuk, who seems like a genuinely modest man, batted away any such grandiosity. "I have described the adventures of my nation in various ways," was all he would say, without acknowledging that you could apply the very same formula to Leaves of Grass or The Divine Comedy.As an interlocutor, Atwood was perfectly okay. At times I wondered whether Rushdie himself--no novice when it comes to fictional explorations of shame and pride--might have been more in synch with Pamuk, more able to tease out what makes him so distinctive. Yet there was one moment that seemed to comically encapsulate Pamuk's tone, with its murmuring disclosures and meaningful silences. "I'm going ask you a personal question," Atwood said, "but you don't have to answer it." The guest of honor paused. Then he replied: "Okay. If I answer, you don't have to listen."

Monday, April 24, 2006

VSP, Shostakovich

There was just a long, kettle-drum-like roll of thunder outside. Inside, warm and dry, I was thumbing through Jeremy Treglown's biography of V.S. Pritchett, and came across this excellent bit from Sir Victor:

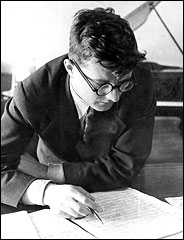

On a different note: we went to see Mstislav Rostropovich conduct Shostakovich's Violin Concerto No. 1 and Symphony No. 5 on Saturday night. At age 79, the conductor looked a little frail--his black jacket seemed to hang off his shoulders--and I wondered whether there would be many more opportunities to hear him play the cello (his version of the Debussy Cello Sonata with Benjamin Britten on piano is one of my favorite recordings ever). Yet his very presence on the podium was amazing to contemplate. Rostropovich's friendship with the composer goes back to 1943, when the 16-year-old cellist attended his orchestration classes at the Moscow Conservatoire. Nearly two decades later, in 1959, Shostakovich wrote the First Cello Concerto expressly for his old pupil. Flattered to the max, Rostropovich hurried to Leningrad and spent three days memorizing his part. His performance (using a skeleton score for piano and cello) greatly moved the composer, and as Rostropovich recounts in Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, he was soon the recipient of not one but three fan letters:

On a different note: we went to see Mstislav Rostropovich conduct Shostakovich's Violin Concerto No. 1 and Symphony No. 5 on Saturday night. At age 79, the conductor looked a little frail--his black jacket seemed to hang off his shoulders--and I wondered whether there would be many more opportunities to hear him play the cello (his version of the Debussy Cello Sonata with Benjamin Britten on piano is one of my favorite recordings ever). Yet his very presence on the podium was amazing to contemplate. Rostropovich's friendship with the composer goes back to 1943, when the 16-year-old cellist attended his orchestration classes at the Moscow Conservatoire. Nearly two decades later, in 1959, Shostakovich wrote the First Cello Concerto expressly for his old pupil. Flattered to the max, Rostropovich hurried to Leningrad and spent three days memorizing his part. His performance (using a skeleton score for piano and cello) greatly moved the composer, and as Rostropovich recounts in Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, he was soon the recipient of not one but three fan letters:

How touching and hapless one's elders looked when one spotted them on their own: lonely Shaw looking into the window of the gun shop in the Strand, Wells with a fly button undone in a club, Yeats with a detective novel fallen on his chest, Chesterton at the window of a pub restaurant off Leicester Square, also asleep, with his head on the table-top marble--the clown in all the passive dignity of private life.Fascinating and strange. London sounds like a vast petting zoo of narcoleptic geniuses. Then again, we all know what he's talking about. Why, just the other day I saw Toni Morrison at the Dunkin' Donuts again, slumped over her French cruller and coffee.

On a different note: we went to see Mstislav Rostropovich conduct Shostakovich's Violin Concerto No. 1 and Symphony No. 5 on Saturday night. At age 79, the conductor looked a little frail--his black jacket seemed to hang off his shoulders--and I wondered whether there would be many more opportunities to hear him play the cello (his version of the Debussy Cello Sonata with Benjamin Britten on piano is one of my favorite recordings ever). Yet his very presence on the podium was amazing to contemplate. Rostropovich's friendship with the composer goes back to 1943, when the 16-year-old cellist attended his orchestration classes at the Moscow Conservatoire. Nearly two decades later, in 1959, Shostakovich wrote the First Cello Concerto expressly for his old pupil. Flattered to the max, Rostropovich hurried to Leningrad and spent three days memorizing his part. His performance (using a skeleton score for piano and cello) greatly moved the composer, and as Rostropovich recounts in Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, he was soon the recipient of not one but three fan letters:

On a different note: we went to see Mstislav Rostropovich conduct Shostakovich's Violin Concerto No. 1 and Symphony No. 5 on Saturday night. At age 79, the conductor looked a little frail--his black jacket seemed to hang off his shoulders--and I wondered whether there would be many more opportunities to hear him play the cello (his version of the Debussy Cello Sonata with Benjamin Britten on piano is one of my favorite recordings ever). Yet his very presence on the podium was amazing to contemplate. Rostropovich's friendship with the composer goes back to 1943, when the 16-year-old cellist attended his orchestration classes at the Moscow Conservatoire. Nearly two decades later, in 1959, Shostakovich wrote the First Cello Concerto expressly for his old pupil. Flattered to the max, Rostropovich hurried to Leningrad and spent three days memorizing his part. His performance (using a skeleton score for piano and cello) greatly moved the composer, and as Rostropovich recounts in Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered, he was soon the recipient of not one but three fan letters:Shortly after my return to Moscow I received three letters from Shostakovich, which became my most treasured possessions. They were like love-letters, and became a kind of talisman for me. I kept them by my bedside table and read them constantly. The first letter started with these words, "Slava, I am completely intoxicated by what you have done to me, by the sheer delight you have given to me." I don't wish to continue to quote Dmitri Dmitriyevich's words, as they would sound completely implausible. Then one fine day I couldn't find the letters. I asked our maid Rimma where they were. She had seen me hunting for them high and low for three days, but she was too frightened to tell me straight away that she had thrown these treasured letters into the rubbish bin.Anyway, Maxim Vengerov played the Violin Concerto, with its desolate slow movements and frantic, high-stepping Scherzo and Burlesque. He was tremendous. The first movement is a killer--13 minutes of nonstop pain and perplexion--and Vengerov kept the momentum going the whole time. His intonation is beautiful and his fast, narrow vibrato seems perfect for this music, which should never sound mawkish. It's somber stuff. Even the fast movements, with their rocking tempi and grimacing xylophone parts, have a nervous intensity to them. (You try smiling when Stalin is standing on your toes--or your neck.) A bummer, no? For the listener, though, there's a paradoxical payoff: joy.

Friday, April 21, 2006

Aldo Buzzi's "Peace"

Readers of HOM will already be familiar with my Aldo Buzzi mania. Anyway, I was trawling the Web the other day and came across this brief poem, which appeared in La Repubblica on October 12, 2005, and was subsequently posted on this blog. It is, I soon realized, nearly translation-proof. Why? Buzzi is toying with two different Italian cliches: la goccia che fa traboccare il vaso (the drop that makes the vessel overflow) and the more familiar la paglia che fa stramazzare il cammello (the straw that breaks the camel's back). But normally English translators simply substitute the second cliche for the first one, since we don't have an exact, idiomatic equivalent for la goccia che fa traboccare il vaso. Sigh. Anyway, that didn't stop me from wading directly in and making a quick-and-dirty translation. Here it is, along with a jazzy photo of the youthful Aldo, which should probably be titled Portrait of the Artist as a Young Rake.

Readers of HOM will already be familiar with my Aldo Buzzi mania. Anyway, I was trawling the Web the other day and came across this brief poem, which appeared in La Repubblica on October 12, 2005, and was subsequently posted on this blog. It is, I soon realized, nearly translation-proof. Why? Buzzi is toying with two different Italian cliches: la goccia che fa traboccare il vaso (the drop that makes the vessel overflow) and the more familiar la paglia che fa stramazzare il cammello (the straw that breaks the camel's back). But normally English translators simply substitute the second cliche for the first one, since we don't have an exact, idiomatic equivalent for la goccia che fa traboccare il vaso. Sigh. Anyway, that didn't stop me from wading directly in and making a quick-and-dirty translation. Here it is, along with a jazzy photo of the youthful Aldo, which should probably be titled Portrait of the Artist as a Young Rake.Look: here is the drop

That makes the camel overflow,

The straw

That breaks the vessel’s back.

The drop that breaks the vessel’s back,

The straw that makes the camel overflow,

The vessel that breaks the drop’s back,

The drop that breaks the straw’s back,

The straw

Whose immersion of the drop

Fails to break

The goddamn camel’s back.

But now, finally: peace.

The blessed drop falls,

The vessel overflows.

And you, blessed straw,

Add your burden to the staggering, cursed camel

And break its back.

Thursday, April 20, 2006

Intermission

I'm going to get some lunch now. Then I'll return to broadcasting my every stray thought. Isn't this blogging thing great?

Then again

It seems like only yesterday that I was ragging on Elizabeth Bishop for rhyming "then" and "again." What an amateur! But just a couple of hours ago, while I was taking a shower and humming a little tune, which turned out to be the theme from Mannix (thank you, Steve Augustine), I recalled some beautiful lines from Auden's "A Summer Night." Whoops: hasn't Auden committed a similar crime?

That later we, though parted then,No, he brought it off. The reason being that in "A Summer Night," there's a metaphysical abyss between "then" and "when"--experience on one side, innocence on the other. Using the shopworn vocabulary amounts to a kind of reticence, a muffled acknowledgment that what's past is past. Don't take my word for it. Read the whole poem--which will gradually engrave itself upon your brain--and see what I mean. While we're at it, Auden's famous explanation of how he came to write the poem has always fascinated me:

May still recall these evenings when

Fear gave his watch no look;

The lion griefs loped from the shade

And on our knees their muzzles laid,

And Death put down his book.

One fine summer night in June 1933 I was sitting on a lawn after dinner with three colleagues, two women and one man. We liked each other well enough but were certainly not intimate friends, nor had any of us a sexual interest in another. Incidentally, we had not drunk any alcohol. We were talking casually about everyday matters when, quite suddenly and unexpectedly, something happened. I felt myself invaded by a power which, though I consented to it, was irresistible and certainly not mine. For the first time in my life I knew exactly--because, thanks to the power, I was doing it--what it means to love one’s neighbour as oneself. I was also certain, though the conversation continued to be perfectly ordinary, that my three colleagues were having the same experience. (In the case of one of them, I was later able to confirm this.)

TV, Threepenny Opera, Brummelliana

The other night we rented the final episode of Six Feet Under, and as we watched one character after another shuffle off this mortal coil, I had tears in my eyes the whole time. I could see, even as I wept, little defects in the production: some of the shots of the youngest daughter driving East looked like car commercials, and in their elderly incarnation, almost all the characters seemed to be wearing the identical, white, stringy wig. It was a crude touch, that wig, in a show so attentive to physical detail. Yet it did remind me of an exalted precedent: the scene at the end of Proust where the narrator attends a party and can hardly recognize his aged friends. Being Proust, he doesn't note the phenomenon and move on--he dwells on it for many pages, in those lengthy, oxygen-deprived sentences that are his trademark:

That brilliant simile--yoking together a scientific tidbit with our intimations of mortality--puts Proust on a higher plane than Alan Ball. Fair enough. Yet Six Feet Under is amazing in its own way, and it passed the ultimate litmus test: it moved me. It caused my moderately jaundiced heart to skip a beat or two. Which is more than I can say for the production of The Threepenny Opera I saw on Saturday afternoon. Confirmed Brechtians will argue that I wasn't supposed to be moved--you know, the old alienation effect in action. But the technical difficulties on display here didn't leave me alienated, either, just pleasantly disgruntled. First problem: despite its flagrant artificiality, Threepenny Opera cries out for a charismatic and scary leading man, who can give Macheath some palpable, non-artificial menace. The gifted Alan Cumming, speaking with a broad Scots accent, was far too cute: you wanted to hug him (although you might want to shower afterwards.) Jim Dale, on the other hand, did Mr. Peachum in a broad Cockney accent. And Nellie McKay, making her debut on Broadway, read her lines in the honey-dipped cadences of an MGM ingenue. This is a problem. So is the erratic tone of the production itself, with its frequent mood swings from pathos to camp to mild titillation (think Love, American Style with a dash of Weimar decadence).

On the plus side, the music fared pretty damn well. What the audience really responded to was Cyndi Lauper (!) singing "Solomon Song" in the second act, precisely because she was allowed to play it straight. And while the latter-day interpreters of "Mack the Knife"--including Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Frank Sinatra--have turned the song into an anthem of ring-a-ding-ding insouciance, Kurt Weill's melody sounds very different in context, with the whole ensemble trading lines: it's sad, sardonic, and strangely haunting. Which is, I believe, what Brecht had in mind.

On the plus side, the music fared pretty damn well. What the audience really responded to was Cyndi Lauper (!) singing "Solomon Song" in the second act, precisely because she was allowed to play it straight. And while the latter-day interpreters of "Mack the Knife"--including Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Frank Sinatra--have turned the song into an anthem of ring-a-ding-ding insouciance, Kurt Weill's melody sounds very different in context, with the whole ensemble trading lines: it's sad, sardonic, and strangely haunting. Which is, I believe, what Brecht had in mind.

Well, nobody said irony would be easy. Hazlitt was already worrying the question back in 1828, when he published his ruminations on Beau Brummell in the London Weekly Review. It was Brummell's dandyish, deadpan wit that intrigued him--the microscopic distinctions, the triviality as comic tinder. In "Brummelliana" (love that title) Hazlitt wrote:

For Proust it's not simply a matter of observing how time has transformed his friends. He's also interested in how oblivious we are to our own physical decay--those terrible, tiny increments--and how we tend to live in a state of death-defying innocence. What sets us straight is the shock of seeing other people grow old. Only then, Proust notes, are we reminded of "that chronological reality which under normal conditions is no more than an abstract conception to us, just as the first sight of some strange dwarf tree or giant baobab apprises us that we have arrived in a new latititude."For a few seconds I did not understand why it was that I had difficulty in recognizing the master of the house and the guests and why everyone in the room appeared to have put on a disguise--in most cases a powdered wig--which changed him completely. The Prince himself, as he stood receiving his guests, still had that genial look of a king in a fairy-story which I had remarked in him the first time I had been to his house, but to-day, as though he too felt bound to comply with the rules for fancy dress which he had sent out with the invitations, he had got himself up with a white beard and dragged his feet along the ground as though they were weighted with soles of lead, so that he gave the impression of trying to impersonate one of the "Ages of Man."

That brilliant simile--yoking together a scientific tidbit with our intimations of mortality--puts Proust on a higher plane than Alan Ball. Fair enough. Yet Six Feet Under is amazing in its own way, and it passed the ultimate litmus test: it moved me. It caused my moderately jaundiced heart to skip a beat or two. Which is more than I can say for the production of The Threepenny Opera I saw on Saturday afternoon. Confirmed Brechtians will argue that I wasn't supposed to be moved--you know, the old alienation effect in action. But the technical difficulties on display here didn't leave me alienated, either, just pleasantly disgruntled. First problem: despite its flagrant artificiality, Threepenny Opera cries out for a charismatic and scary leading man, who can give Macheath some palpable, non-artificial menace. The gifted Alan Cumming, speaking with a broad Scots accent, was far too cute: you wanted to hug him (although you might want to shower afterwards.) Jim Dale, on the other hand, did Mr. Peachum in a broad Cockney accent. And Nellie McKay, making her debut on Broadway, read her lines in the honey-dipped cadences of an MGM ingenue. This is a problem. So is the erratic tone of the production itself, with its frequent mood swings from pathos to camp to mild titillation (think Love, American Style with a dash of Weimar decadence).

On the plus side, the music fared pretty damn well. What the audience really responded to was Cyndi Lauper (!) singing "Solomon Song" in the second act, precisely because she was allowed to play it straight. And while the latter-day interpreters of "Mack the Knife"--including Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Frank Sinatra--have turned the song into an anthem of ring-a-ding-ding insouciance, Kurt Weill's melody sounds very different in context, with the whole ensemble trading lines: it's sad, sardonic, and strangely haunting. Which is, I believe, what Brecht had in mind.

On the plus side, the music fared pretty damn well. What the audience really responded to was Cyndi Lauper (!) singing "Solomon Song" in the second act, precisely because she was allowed to play it straight. And while the latter-day interpreters of "Mack the Knife"--including Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Frank Sinatra--have turned the song into an anthem of ring-a-ding-ding insouciance, Kurt Weill's melody sounds very different in context, with the whole ensemble trading lines: it's sad, sardonic, and strangely haunting. Which is, I believe, what Brecht had in mind.Well, nobody said irony would be easy. Hazlitt was already worrying the question back in 1828, when he published his ruminations on Beau Brummell in the London Weekly Review. It was Brummell's dandyish, deadpan wit that intrigued him--the microscopic distinctions, the triviality as comic tinder. In "Brummelliana" (love that title) Hazlitt wrote:

So we may say of Mr Brummell's jests, that they are of a meaning so attenuated that "nothing lives 'twixt them and nonsense":--they hover on the very brink of vacancy, and are in their shadowy composition next of kin to nonentities. It is impossible for anyone to go beyond him without falling flat into insignificance and insipidity: he has touched the ne plus ultra that divides the dandy from the dunce. But what a fine eye to discriminate: what a sure hand to hit this last and thinnest of all intellectual partitions!Dandy or dunce? There should be a litmus test for that, too.

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Go easy on the cuticles

The folks at failbetter.com have posted a short email exchange with Anne Tyler. This is a rarity, given the author's well-known aversion to publicity and pontification. ("Any time I talk in public about writing," she notes,"I end up not able to do any writing. It's as if some capricious Writing Elf goes into a little sulk whenever I expose him.") Happily she consented to share a few thoughts about her upcoming novel, Digging to America, in which two Baltimore couples adopt Korean babies. Praising one key scene--in which the babies and adoptive mothers first arrive in the country--Margo Rabb asks Tyler whether the details are predominantly invented or recalled. Her answer:

The folks at failbetter.com have posted a short email exchange with Anne Tyler. This is a rarity, given the author's well-known aversion to publicity and pontification. ("Any time I talk in public about writing," she notes,"I end up not able to do any writing. It's as if some capricious Writing Elf goes into a little sulk whenever I expose him.") Happily she consented to share a few thoughts about her upcoming novel, Digging to America, in which two Baltimore couples adopt Korean babies. Praising one key scene--in which the babies and adoptive mothers first arrive in the country--Margo Rabb asks Tyler whether the details are predominantly invented or recalled. Her answer:Like almost everyone, I have been a fascinated bystander at more than a few of those arrival scenes. But the specific details of the arrival scene in my book are manufactured, and it is always imagination I rely upon rather than my own memory--which is, I've found, disconcertingly focused, in a not very helpful way. (I might have only the vaguest, blurriest recollection of someone, but his cushioned-looking, bitten-down fingernails will stay with me forever.)

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Vinicius Cantuária

In 1963, pressed to describe the art of his compatriot João Gilberto, the pianist and composer Antonio Carlos Jobim sketched out a kind of push-and-pull operation: "He was pulling the guitar one way and singing the other way. It created a third thing that was profound." No doubt this was a casual comment. In more ways than one, however, it goes straight to the heart of Brazilian music.

For starters, it alludes to that loping, rhythmic displacement that gives so much of the music its trademark propulsion. It also underlines the music's status as a magnificent hybrid--a third thing. Now, all pop music is a matter of cross-pollination. But the Brazilians have mixed and matched their influences with unusual gusto. Roughly speaking, the samba emerged from a three-way dalliance among Angolan dance (the lundu), the mazurka-inflected choro, and American show tunes. Bossa nova added a supple harmonic sense, much of it derived from 1950s-era "cool" jazz, along with Gilberto's gently percussive touch on the guitar. And these styles in turn begat the Brazilian spin on post-Beatles rock, tropicalismo, which devoured everything in its path--folk, reggae, salsa, psychedelia, Tin Pan Alley--without ever quite abandoning its indigenous roots.

For starters, it alludes to that loping, rhythmic displacement that gives so much of the music its trademark propulsion. It also underlines the music's status as a magnificent hybrid--a third thing. Now, all pop music is a matter of cross-pollination. But the Brazilians have mixed and matched their influences with unusual gusto. Roughly speaking, the samba emerged from a three-way dalliance among Angolan dance (the lundu), the mazurka-inflected choro, and American show tunes. Bossa nova added a supple harmonic sense, much of it derived from 1950s-era "cool" jazz, along with Gilberto's gently percussive touch on the guitar. And these styles in turn begat the Brazilian spin on post-Beatles rock, tropicalismo, which devoured everything in its path--folk, reggae, salsa, psychedelia, Tin Pan Alley--without ever quite abandoning its indigenous roots.

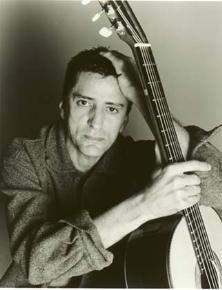

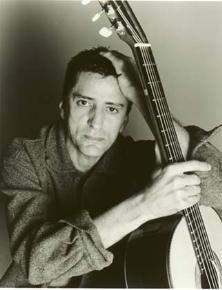

The prime mover of tropicalismo, of course, was Caetano Veloso, whose dedication to boundary-busting (and left-leaning) performance earned him both a short prison term and a three-year-long exile in 1969. More than three decades later, at age 62, Veloso shows no sign of flagging. But if he ever cares to pass the torch, I'd be happy to suggest a recipient: the guitarist and singer-songwriter Vinicius Cantuária.

Born in Manaus, Brazil, Cantuária moved to Rio with his family when he was seven. After cutting his teeth with a rock band, O Terco, during the 1970s, he spent much of the next ten years performing with Veloso, mostly as a percussionist. Yet he quickly outgrew the role of the anonymous sideman. His composition "Lua E Estrella" became Veloso's biggest hit in 1981, and it's clear that the current of inspiration flowed both ways, regardless of who was topping the bill. When Cantuária released his 1996 U.S. debut, Sol Na Cara, the very first track was a collaboration with his former employer. He also continues to include such Veloso-penned gems as "Jóia" in his concerts, and to emulate the skittish poetry of his lyrics.

Yet Cantuária is very much his own man, as Sol Na Cara made clear. Released around the same time the artist relocated from Rio to Brooklyn, the recording is essentially a duet with Ryuichi Sakamoto, whose keyboard and synthesizer parts added an alluring layer of electronica to Cantuári's traditionalism.

Stripped of Sakamoto's overdubs, cuts like "Samba Da Estrela" or "O Nome Dela" might well have sounded like elegant throwbacks to João Gilberto (not such a bad thing, after all). But with Cantuária's nylon-string guitar and plaintive vocals weaving in and out of his partner's electronic adornments, the result was something very different. The banked fires of the bossa nova--where sex is so clearly implicated in every syllable that nobody really needs to be explicit about it--finally entered the digital age. The music was warm and cool, intimate and expansive. It also paved the way for such neo-bossa stars as Bebel Gilberto and Moreno Veloso, both of whom had absorbed the music quite literally at their father’s knee.

Cantuária, meanwhile, upped the ante with his next CD, Tucumã. This 1999 recording is named after a rare fruit that grows only in the Amazon basin--and the music, too, with its sleepy syncopation and erotic melancholy, could have come from nowhere but Brazil. Still, Cantuária was now making his home in America. That allowed him to recruit a dream team of session players, including Bill Frisell, Joey Baron, Michael Leonhart, Laurie Anderson, and Erik Friedlander (a gifted cellist whose undulant countermelodies recall Jaques Morelenbaum's work with Veloso).

Cantuária, meanwhile, upped the ante with his next CD, Tucumã. This 1999 recording is named after a rare fruit that grows only in the Amazon basin--and the music, too, with its sleepy syncopation and erotic melancholy, could have come from nowhere but Brazil. Still, Cantuária was now making his home in America. That allowed him to recruit a dream team of session players, including Bill Frisell, Joey Baron, Michael Leonhart, Laurie Anderson, and Erik Friedlander (a gifted cellist whose undulant countermelodies recall Jaques Morelenbaum's work with Veloso).

The presence of such downtown jazz luminaries as Frisell and Baron--and the fact that Verve released the disc--might have suggested a newfangled version of Jazz Samba, the 1962 session that made Jobim a household word and Stan Getz a wealthy man. Tucumã, however, was considerably harder to classify. It was also one of the most beautiful recordings of the decade, genre be damned.

On a cut like "Amor Brasileiro," Frisell's electric guitar flickers in the background like heat lightning while Cantuária murmurs sweet nothings--which sound so much more persuasive in Portuguese!--in his lover's ear: Sigo te amando sigo querendo tudo contigo / Pode apagar a luz ("I go on loving you, I go on wanting it all with you / Turn off the light now"). Elsewhere the texture thickens, to delightful effect. "Aracajú," an impressionistic valentine to Brazil itself, begins with a fairly minimal layer of acoustic guitar and percussion. But soon enough Cantuária adds Indian wood flute and some ominous samples, which manage to suggest both a careening string section and a nasty traffic jam. "Pra Gil" combines a drowsy groove with a gorgeous cello obbligato, "Sanfona" boasts a vaguely Byrds-like 12-string hook, "Igarapé" resembles Villa-Lobos in slow motion, and... well, you get the picture. Like a good postmodernist, Cantuária borrowed from everybody. Unlike many, he repaid his debts with exquisite interest.

With its dense and delicate mix, Tucumã was very much a studio creation, a product of the auditory hothouse. Cantuaria's 2001 follow-up, Vinicius, saw him returning to a more naturalistic sound. He hadn't, to be sure, renounced his eclectic instincts: on a cut like "Ordinaria," Michael Leonhart's muted trumpet and Jenny Scheinman's violin produced a kind of airborne mood music, one part Lalo Schifrin to one part Miles Davis. And the mixture of Brad Meldau's piano with Frisell's loop-the-loops on "Nova de Sete" was a scintillating oddity.

Still, this was a more pared-down performance than its predecessor, with an extra nod to Brazilian tradition. "Quase Choro" tipped its hat to the century-old choro, however obliquely. And Cantuária revived "Ela é Carioca," a Jobim classic that remains a staple of his live shows, with his introverted gringo audiences doing their best to sing along on the chorus. Not surprisingly, Cantuária's understated vocal echoed João Gilberto's--and not surprisingly, there was a layer of Frisellian icing on the cake, just to remind us that it wasn't 1959 anymore.

To a great extent, Cantuária's two releases since then reflect his efforts to translate his studio magic into a live setting. Live: Skirball Cultural Center 8/7/03 captures his quintet on what sounds like a decent soundboard tape (the label, a tiny Santa Monica outfit called Kufala, has made a specialty out of such seat-of-the-pants recordings.) It sums up both his strengths as a live performer and a handful of weaknesses.

On the plus side, there's the formidable ensemble of Scheinman, Sergio Brandao on bass, Paulo Braga on drums, and Nanny Assis on percussion. Cantuária himself pitches in on electric guitar--a big hollow-body, hooked up to a cascade of electronic effects that would do Frisell proud. What these guys (and one gal) supply in spades are grooves, with plenty of bottom and polyrhythmic décor. On the first cut, Gilberto Gil's "Procissão," the leader teases the audience for a good six minutes, doodling with the chords over triangle-and-shaker percussion, before the band lunges in behind him. "O Nome Dela" (from Sol Na Cara) gets a similar treatment: a hushed intro followed by a percolating workout.

The caveat, however, is that a certain amount of Cantuária's subtlety gets lost in the shuffle. Just compare his version of "Vivo Isolado do Mundo" on Tucumã--gentle, unhurried, and with a piercing sadness--to the one here, where the leader kicks the tempo up a notch and leads the band through another high-energy frolic.

It feels churlish to complain about such a rollicking performance, and no fan will want to be without the Kufala release. Still, I find myself missing the emotional chiaroscuro of Cantuária's best work, and his delicacy on the nylon-string guitar, clearly banished from the concert stage. Well, the artist--or the A&R guy at Bar/None Records--must have read my mind, because his 2004 release offers a marvelous fusion of his two personae.

It feels churlish to complain about such a rollicking performance, and no fan will want to be without the Kufala release. Still, I find myself missing the emotional chiaroscuro of Cantuária's best work, and his delicacy on the nylon-string guitar, clearly banished from the concert stage. Well, the artist--or the A&R guy at Bar/None Records--must have read my mind, because his 2004 release offers a marvelous fusion of his two personae.

On Horse and Fish he employs his current touring band, with Michael Leonhart subbing for Scheinman and Paul Socolow on bass. The repertoire is mostly familiar, including four cuts that also appear the Kufala set. Yet the approach is very different. The leader breaks out his acoustic guitar for much of the session, and while the band pumps its way through such dance-floor vehicles as "Procissão” and "Cubanos Postizos," they apply a delicate touch indeed to "Quase Choro," "Perritos," or the breezy, swaying "O Barquinho." The recording is pristine, and miked so closely that Cantuária sounds like he's in your living room, or boudoir. In terms of sheer sonic delight, this may be the best thing I've heard since, well, Tucumã.

What Cantuária will do next is, of course, an open question. Will he opt for studio wizardry, or the adrenaline rush of performance, or steer a course down the middle? I'll look forward to finding out. In the meantime, he's already produced a stunning body of work, beautifully triangulating between Brazil and Brooklyn--and that, as Jobim might have said, is something profound.

CODA: I wrote this piece in 2004 for a magazine that never got off the ground. Since then Cantuária has released another CD, Silva (Hannibal), which elegantly mingles his own overdubbed guitars, percussion, vocals, and loops with a string quartet. Think of it as an acoustic spin on Sol Na Cara, with the strings and Michael Leonhart's minimalist trumpet pinch-hitting for Sakamoto's electronica. A hair less intimate than Horse and Fish, this recording does share the warmth and high-gloss finish of its predecessor. My guess is that Cantuária will opt for a more naturalistic sound on the next one, but in either guise--live wire or studio perfectionist--he remains an enchanting artist.

For starters, it alludes to that loping, rhythmic displacement that gives so much of the music its trademark propulsion. It also underlines the music's status as a magnificent hybrid--a third thing. Now, all pop music is a matter of cross-pollination. But the Brazilians have mixed and matched their influences with unusual gusto. Roughly speaking, the samba emerged from a three-way dalliance among Angolan dance (the lundu), the mazurka-inflected choro, and American show tunes. Bossa nova added a supple harmonic sense, much of it derived from 1950s-era "cool" jazz, along with Gilberto's gently percussive touch on the guitar. And these styles in turn begat the Brazilian spin on post-Beatles rock, tropicalismo, which devoured everything in its path--folk, reggae, salsa, psychedelia, Tin Pan Alley--without ever quite abandoning its indigenous roots.

For starters, it alludes to that loping, rhythmic displacement that gives so much of the music its trademark propulsion. It also underlines the music's status as a magnificent hybrid--a third thing. Now, all pop music is a matter of cross-pollination. But the Brazilians have mixed and matched their influences with unusual gusto. Roughly speaking, the samba emerged from a three-way dalliance among Angolan dance (the lundu), the mazurka-inflected choro, and American show tunes. Bossa nova added a supple harmonic sense, much of it derived from 1950s-era "cool" jazz, along with Gilberto's gently percussive touch on the guitar. And these styles in turn begat the Brazilian spin on post-Beatles rock, tropicalismo, which devoured everything in its path--folk, reggae, salsa, psychedelia, Tin Pan Alley--without ever quite abandoning its indigenous roots.The prime mover of tropicalismo, of course, was Caetano Veloso, whose dedication to boundary-busting (and left-leaning) performance earned him both a short prison term and a three-year-long exile in 1969. More than three decades later, at age 62, Veloso shows no sign of flagging. But if he ever cares to pass the torch, I'd be happy to suggest a recipient: the guitarist and singer-songwriter Vinicius Cantuária.

Born in Manaus, Brazil, Cantuária moved to Rio with his family when he was seven. After cutting his teeth with a rock band, O Terco, during the 1970s, he spent much of the next ten years performing with Veloso, mostly as a percussionist. Yet he quickly outgrew the role of the anonymous sideman. His composition "Lua E Estrella" became Veloso's biggest hit in 1981, and it's clear that the current of inspiration flowed both ways, regardless of who was topping the bill. When Cantuária released his 1996 U.S. debut, Sol Na Cara, the very first track was a collaboration with his former employer. He also continues to include such Veloso-penned gems as "Jóia" in his concerts, and to emulate the skittish poetry of his lyrics.

Yet Cantuária is very much his own man, as Sol Na Cara made clear. Released around the same time the artist relocated from Rio to Brooklyn, the recording is essentially a duet with Ryuichi Sakamoto, whose keyboard and synthesizer parts added an alluring layer of electronica to Cantuári's traditionalism.

Stripped of Sakamoto's overdubs, cuts like "Samba Da Estrela" or "O Nome Dela" might well have sounded like elegant throwbacks to João Gilberto (not such a bad thing, after all). But with Cantuária's nylon-string guitar and plaintive vocals weaving in and out of his partner's electronic adornments, the result was something very different. The banked fires of the bossa nova--where sex is so clearly implicated in every syllable that nobody really needs to be explicit about it--finally entered the digital age. The music was warm and cool, intimate and expansive. It also paved the way for such neo-bossa stars as Bebel Gilberto and Moreno Veloso, both of whom had absorbed the music quite literally at their father’s knee.

Cantuária, meanwhile, upped the ante with his next CD, Tucumã. This 1999 recording is named after a rare fruit that grows only in the Amazon basin--and the music, too, with its sleepy syncopation and erotic melancholy, could have come from nowhere but Brazil. Still, Cantuária was now making his home in America. That allowed him to recruit a dream team of session players, including Bill Frisell, Joey Baron, Michael Leonhart, Laurie Anderson, and Erik Friedlander (a gifted cellist whose undulant countermelodies recall Jaques Morelenbaum's work with Veloso).

Cantuária, meanwhile, upped the ante with his next CD, Tucumã. This 1999 recording is named after a rare fruit that grows only in the Amazon basin--and the music, too, with its sleepy syncopation and erotic melancholy, could have come from nowhere but Brazil. Still, Cantuária was now making his home in America. That allowed him to recruit a dream team of session players, including Bill Frisell, Joey Baron, Michael Leonhart, Laurie Anderson, and Erik Friedlander (a gifted cellist whose undulant countermelodies recall Jaques Morelenbaum's work with Veloso).The presence of such downtown jazz luminaries as Frisell and Baron--and the fact that Verve released the disc--might have suggested a newfangled version of Jazz Samba, the 1962 session that made Jobim a household word and Stan Getz a wealthy man. Tucumã, however, was considerably harder to classify. It was also one of the most beautiful recordings of the decade, genre be damned.

On a cut like "Amor Brasileiro," Frisell's electric guitar flickers in the background like heat lightning while Cantuária murmurs sweet nothings--which sound so much more persuasive in Portuguese!--in his lover's ear: Sigo te amando sigo querendo tudo contigo / Pode apagar a luz ("I go on loving you, I go on wanting it all with you / Turn off the light now"). Elsewhere the texture thickens, to delightful effect. "Aracajú," an impressionistic valentine to Brazil itself, begins with a fairly minimal layer of acoustic guitar and percussion. But soon enough Cantuária adds Indian wood flute and some ominous samples, which manage to suggest both a careening string section and a nasty traffic jam. "Pra Gil" combines a drowsy groove with a gorgeous cello obbligato, "Sanfona" boasts a vaguely Byrds-like 12-string hook, "Igarapé" resembles Villa-Lobos in slow motion, and... well, you get the picture. Like a good postmodernist, Cantuária borrowed from everybody. Unlike many, he repaid his debts with exquisite interest.

With its dense and delicate mix, Tucumã was very much a studio creation, a product of the auditory hothouse. Cantuaria's 2001 follow-up, Vinicius, saw him returning to a more naturalistic sound. He hadn't, to be sure, renounced his eclectic instincts: on a cut like "Ordinaria," Michael Leonhart's muted trumpet and Jenny Scheinman's violin produced a kind of airborne mood music, one part Lalo Schifrin to one part Miles Davis. And the mixture of Brad Meldau's piano with Frisell's loop-the-loops on "Nova de Sete" was a scintillating oddity.

Still, this was a more pared-down performance than its predecessor, with an extra nod to Brazilian tradition. "Quase Choro" tipped its hat to the century-old choro, however obliquely. And Cantuária revived "Ela é Carioca," a Jobim classic that remains a staple of his live shows, with his introverted gringo audiences doing their best to sing along on the chorus. Not surprisingly, Cantuária's understated vocal echoed João Gilberto's--and not surprisingly, there was a layer of Frisellian icing on the cake, just to remind us that it wasn't 1959 anymore.

To a great extent, Cantuária's two releases since then reflect his efforts to translate his studio magic into a live setting. Live: Skirball Cultural Center 8/7/03 captures his quintet on what sounds like a decent soundboard tape (the label, a tiny Santa Monica outfit called Kufala, has made a specialty out of such seat-of-the-pants recordings.) It sums up both his strengths as a live performer and a handful of weaknesses.

On the plus side, there's the formidable ensemble of Scheinman, Sergio Brandao on bass, Paulo Braga on drums, and Nanny Assis on percussion. Cantuária himself pitches in on electric guitar--a big hollow-body, hooked up to a cascade of electronic effects that would do Frisell proud. What these guys (and one gal) supply in spades are grooves, with plenty of bottom and polyrhythmic décor. On the first cut, Gilberto Gil's "Procissão," the leader teases the audience for a good six minutes, doodling with the chords over triangle-and-shaker percussion, before the band lunges in behind him. "O Nome Dela" (from Sol Na Cara) gets a similar treatment: a hushed intro followed by a percolating workout.

The caveat, however, is that a certain amount of Cantuária's subtlety gets lost in the shuffle. Just compare his version of "Vivo Isolado do Mundo" on Tucumã--gentle, unhurried, and with a piercing sadness--to the one here, where the leader kicks the tempo up a notch and leads the band through another high-energy frolic.

It feels churlish to complain about such a rollicking performance, and no fan will want to be without the Kufala release. Still, I find myself missing the emotional chiaroscuro of Cantuária's best work, and his delicacy on the nylon-string guitar, clearly banished from the concert stage. Well, the artist--or the A&R guy at Bar/None Records--must have read my mind, because his 2004 release offers a marvelous fusion of his two personae.

It feels churlish to complain about such a rollicking performance, and no fan will want to be without the Kufala release. Still, I find myself missing the emotional chiaroscuro of Cantuária's best work, and his delicacy on the nylon-string guitar, clearly banished from the concert stage. Well, the artist--or the A&R guy at Bar/None Records--must have read my mind, because his 2004 release offers a marvelous fusion of his two personae.On Horse and Fish he employs his current touring band, with Michael Leonhart subbing for Scheinman and Paul Socolow on bass. The repertoire is mostly familiar, including four cuts that also appear the Kufala set. Yet the approach is very different. The leader breaks out his acoustic guitar for much of the session, and while the band pumps its way through such dance-floor vehicles as "Procissão” and "Cubanos Postizos," they apply a delicate touch indeed to "Quase Choro," "Perritos," or the breezy, swaying "O Barquinho." The recording is pristine, and miked so closely that Cantuária sounds like he's in your living room, or boudoir. In terms of sheer sonic delight, this may be the best thing I've heard since, well, Tucumã.

What Cantuária will do next is, of course, an open question. Will he opt for studio wizardry, or the adrenaline rush of performance, or steer a course down the middle? I'll look forward to finding out. In the meantime, he's already produced a stunning body of work, beautifully triangulating between Brazil and Brooklyn--and that, as Jobim might have said, is something profound.

CODA: I wrote this piece in 2004 for a magazine that never got off the ground. Since then Cantuária has released another CD, Silva (Hannibal), which elegantly mingles his own overdubbed guitars, percussion, vocals, and loops with a string quartet. Think of it as an acoustic spin on Sol Na Cara, with the strings and Michael Leonhart's minimalist trumpet pinch-hitting for Sakamoto's electronica. A hair less intimate than Horse and Fish, this recording does share the warmth and high-gloss finish of its predecessor. My guess is that Cantuária will opt for a more naturalistic sound on the next one, but in either guise--live wire or studio perfectionist--he remains an enchanting artist.

Thursday, April 13, 2006

Custards in a blind alley

You have be in the right mood for Jonathan Swift--otherwise his savage indignation can grow petulant and grating. Yet Cyril Connolly, in an excellent essay I was just reading on the sofa in my glamorous bathrobe, argues that even Swift was compensating for a soft, compote-like center. He writes: "For it is obvious that everything which was considered most heartless and cynical in him can be viewed as the attempts of a man with a terrible capacity for suffering to escape from it... The misanthropy of Swift is, in fact, one side of the romantic dichotomy. No one is born a Diogenes, or enters the world complaining of a raw deal. One cannont hate humanity to that extent unless one has believed in it; one must have thought man a little lower than the angels before one can concentrate on the organs of elimination." Huzzah! Anyway, this is all a preamble to a little quote from a letter Swift wrote to his friend Charles Ford in 1708. He noted that

You have be in the right mood for Jonathan Swift--otherwise his savage indignation can grow petulant and grating. Yet Cyril Connolly, in an excellent essay I was just reading on the sofa in my glamorous bathrobe, argues that even Swift was compensating for a soft, compote-like center. He writes: "For it is obvious that everything which was considered most heartless and cynical in him can be viewed as the attempts of a man with a terrible capacity for suffering to escape from it... The misanthropy of Swift is, in fact, one side of the romantic dichotomy. No one is born a Diogenes, or enters the world complaining of a raw deal. One cannont hate humanity to that extent unless one has believed in it; one must have thought man a little lower than the angels before one can concentrate on the organs of elimination." Huzzah! Anyway, this is all a preamble to a little quote from a letter Swift wrote to his friend Charles Ford in 1708. He noted thatmen are never more mistaken than when they reflect upon Past things, and from what they retain in their memory, compare them with the present... So I formerly used to envy my own Happiness when I was a Schoolboy, the delicious Holidays, the Saterday afternoon, and the charming Custards in a blind alley; I never considered the Confinement ten hours a day, to nouns and verbs, the Terror of the Rod, the bloddy noses, and broken shins.Charming custards in a blind alley! The story of my life. I would add that Swift was only 41 when he wrote that letter. Certain writers behave like grumpy old men from the moment they set pen to paper, especially knee-jerk misanthropes, whose disgust for the human race might seem unfounded coming from a relative youngster. As for myself, I try to sound like an eternal 39-year-old--just like Jack Benny. (For a look at Swift's death mask, click here. If you scroll down, there's also a snapshot of George Bernard Shaw's backyard privy. Really.)

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

Blythe and Bishop

Sounds like a white-shoe law firm, doesn't it? But no, it's merely me quoting again from Ronald Blythe, then moving on to the recent, barrel-scraping publication of Elizabeth Bishop's leftovers. Here's Blythe on the lubricated Twenties:

And what shall we read? I'm all for Elizabeth Bishop's Edgar Allan Poe & The Juke-Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments. There was a very public (and widely reported) spat between Alice Quinn, who edited and annotated the volume, and Helen Vendler, who tore into the entire project in a lengthy New Republic essay. La Vendler was livid:

And what shall we read? I'm all for Elizabeth Bishop's Edgar Allan Poe & The Juke-Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments. There was a very public (and widely reported) spat between Alice Quinn, who edited and annotated the volume, and Helen Vendler, who tore into the entire project in a lengthy New Republic essay. La Vendler was livid:

William Logan takes this tack in his New Criterion essay, and so does Kerry Fried in a brief but excellent Newsday review. Anything I could add would be superfluous, so I'll simply quote one of the brief poems I like, "Foreign-Domestic." This is not a typical Bishop performance, with its neat tetrameters and a (relatively) conventional sense of whimsy. So what? I love it anyway: a snapshot of domestic bliss, subtly undermined by the corpse-like image of her companion.

The twenties was not a drunken decade as decades go but a revolution in drinking habits, plus the existence of Lady Astor, caused it to sound as though it was. The alcoholic emphasis in much twenties writing (drinking is easily the most boring subject in all literature and it defies sympathetic interpretation by any except the rarest drunkard poets, such as Li Po or Verlaine) is really nothing more than the Briton's eternal plea to have a drink when he feels like it. Before the war it was exceptional to be offered a drink before luncheon or dinner and sherry would be served with the soup. The immediate post-war years found people entering the dining-room very jolly indeed and ever so slightly sick, the reason being the cocktail boom. A great queasy river of manhattans, bronxes and martinis flowing from countless all-too-amateur sources savaged the taste buds and jarred the nervous systems of the middle and upper classes.What, incidentally, is a Bronx? There seems to be some dispute. According to Magnus Bredenbek's What Shall We Drink? (1934), the cocktail was invented around 1900, inspired by a bartender's visit to the Bronx Zoo. A competing theory puts the creation in Philadelphia. In any case, we're talking four parts gin, one part orange juice, and one part Italian Vermouth. What those ingredients have to do with a trot through the Monkey House is anybody's guess.

And what shall we read? I'm all for Elizabeth Bishop's Edgar Allan Poe & The Juke-Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments. There was a very public (and widely reported) spat between Alice Quinn, who edited and annotated the volume, and Helen Vendler, who tore into the entire project in a lengthy New Republic essay. La Vendler was livid:

And what shall we read? I'm all for Elizabeth Bishop's Edgar Allan Poe & The Juke-Box: Uncollected Poems, Drafts, and Fragments. There was a very public (and widely reported) spat between Alice Quinn, who edited and annotated the volume, and Helen Vendler, who tore into the entire project in a lengthy New Republic essay. La Vendler was livid:It will be argued that Bishop could have burned all these pieces of paper if she did not wish them to see publication. (I am told that poets now, fearing an Alice Quinn in their future, are incinerating their drafts.) But burning one's writings is painful, and Bishop kept her papers, as any of us might, because the past was precious to her. Bishop did not expect to die when she did, in 1979, at the age of sixty-eight; her death was sudden and unforeseen. (Even if she had left instructions not to publish her papers, she could not rely on their being obeyed: Max Brod disobeyed Kafka's explicit command to destroy his writings. But some poets have been obeyed: Hopkins asked his sisters to burn his spiritual journals, and they did.) Had Bishop been asked whether her repudiated poems, and some drafts and fragments, should be published after her death, she would have replied, I believe, with a horrified "No."Of course Vendler doesn't really know the answer to that question. What's more, I don't believe she would block the publication of Hopkins's spiritual journals if they were suddenly to surface at, say, a yard sale. As long as the contents of this collection are identified as sublime discards--and Vendler correctly takes The New Yorker to task for sidestepping this duty when they published "Washington as a Surveyor"--then I don't think we're betraying the poet.

William Logan takes this tack in his New Criterion essay, and so does Kerry Fried in a brief but excellent Newsday review. Anything I could add would be superfluous, so I'll simply quote one of the brief poems I like, "Foreign-Domestic." This is not a typical Bishop performance, with its neat tetrameters and a (relatively) conventional sense of whimsy. So what? I love it anyway: a snapshot of domestic bliss, subtly undermined by the corpse-like image of her companion.

I listen to the sweet "eye-fee."Full disclosure: Bishop crossed out all the stuff contained within the square brackets. Her instincts were on target, I think, since the intensity drops off and the final rhyme ("then" and "again") sounds pretty feeble. Do I regret reading the poem in its entirety? Nope.

From where I'm sitting I can see

across the hallway in your room

just two bare feet upon the bed

arranged as if someone were dead,

--a non-crusader on a tomb.

I get up; take a further look.

You're reading a "detective book."

So that's all right. I settle back.

The needle to its destined track

stands true, and from the daedal plate

[an oboe starts to celebrate

escaping from the violin's traps,

--a bit too easily, perhaps,

for the twentieth-century taste,--but then

Vivaldi pulls him down again.]

(Said Blake, "And mutual fear brings peace,

Till the selfish love increase...")

Monday, April 10, 2006

HOM returns (again), Kakutaniana, The Age of Illusion, Ellington clip