Tuesday, April 18, 2006

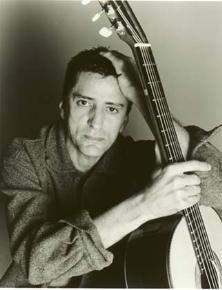

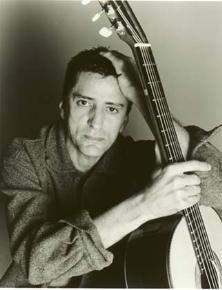

Vinicius Cantuária

In 1963, pressed to describe the art of his compatriot João Gilberto, the pianist and composer Antonio Carlos Jobim sketched out a kind of push-and-pull operation: "He was pulling the guitar one way and singing the other way. It created a third thing that was profound." No doubt this was a casual comment. In more ways than one, however, it goes straight to the heart of Brazilian music.

For starters, it alludes to that loping, rhythmic displacement that gives so much of the music its trademark propulsion. It also underlines the music's status as a magnificent hybrid--a third thing. Now, all pop music is a matter of cross-pollination. But the Brazilians have mixed and matched their influences with unusual gusto. Roughly speaking, the samba emerged from a three-way dalliance among Angolan dance (the lundu), the mazurka-inflected choro, and American show tunes. Bossa nova added a supple harmonic sense, much of it derived from 1950s-era "cool" jazz, along with Gilberto's gently percussive touch on the guitar. And these styles in turn begat the Brazilian spin on post-Beatles rock, tropicalismo, which devoured everything in its path--folk, reggae, salsa, psychedelia, Tin Pan Alley--without ever quite abandoning its indigenous roots.

For starters, it alludes to that loping, rhythmic displacement that gives so much of the music its trademark propulsion. It also underlines the music's status as a magnificent hybrid--a third thing. Now, all pop music is a matter of cross-pollination. But the Brazilians have mixed and matched their influences with unusual gusto. Roughly speaking, the samba emerged from a three-way dalliance among Angolan dance (the lundu), the mazurka-inflected choro, and American show tunes. Bossa nova added a supple harmonic sense, much of it derived from 1950s-era "cool" jazz, along with Gilberto's gently percussive touch on the guitar. And these styles in turn begat the Brazilian spin on post-Beatles rock, tropicalismo, which devoured everything in its path--folk, reggae, salsa, psychedelia, Tin Pan Alley--without ever quite abandoning its indigenous roots.

The prime mover of tropicalismo, of course, was Caetano Veloso, whose dedication to boundary-busting (and left-leaning) performance earned him both a short prison term and a three-year-long exile in 1969. More than three decades later, at age 62, Veloso shows no sign of flagging. But if he ever cares to pass the torch, I'd be happy to suggest a recipient: the guitarist and singer-songwriter Vinicius Cantuária.

Born in Manaus, Brazil, Cantuária moved to Rio with his family when he was seven. After cutting his teeth with a rock band, O Terco, during the 1970s, he spent much of the next ten years performing with Veloso, mostly as a percussionist. Yet he quickly outgrew the role of the anonymous sideman. His composition "Lua E Estrella" became Veloso's biggest hit in 1981, and it's clear that the current of inspiration flowed both ways, regardless of who was topping the bill. When Cantuária released his 1996 U.S. debut, Sol Na Cara, the very first track was a collaboration with his former employer. He also continues to include such Veloso-penned gems as "Jóia" in his concerts, and to emulate the skittish poetry of his lyrics.

Yet Cantuária is very much his own man, as Sol Na Cara made clear. Released around the same time the artist relocated from Rio to Brooklyn, the recording is essentially a duet with Ryuichi Sakamoto, whose keyboard and synthesizer parts added an alluring layer of electronica to Cantuári's traditionalism.

Stripped of Sakamoto's overdubs, cuts like "Samba Da Estrela" or "O Nome Dela" might well have sounded like elegant throwbacks to João Gilberto (not such a bad thing, after all). But with Cantuária's nylon-string guitar and plaintive vocals weaving in and out of his partner's electronic adornments, the result was something very different. The banked fires of the bossa nova--where sex is so clearly implicated in every syllable that nobody really needs to be explicit about it--finally entered the digital age. The music was warm and cool, intimate and expansive. It also paved the way for such neo-bossa stars as Bebel Gilberto and Moreno Veloso, both of whom had absorbed the music quite literally at their father’s knee.

Cantuária, meanwhile, upped the ante with his next CD, Tucumã. This 1999 recording is named after a rare fruit that grows only in the Amazon basin--and the music, too, with its sleepy syncopation and erotic melancholy, could have come from nowhere but Brazil. Still, Cantuária was now making his home in America. That allowed him to recruit a dream team of session players, including Bill Frisell, Joey Baron, Michael Leonhart, Laurie Anderson, and Erik Friedlander (a gifted cellist whose undulant countermelodies recall Jaques Morelenbaum's work with Veloso).

Cantuária, meanwhile, upped the ante with his next CD, Tucumã. This 1999 recording is named after a rare fruit that grows only in the Amazon basin--and the music, too, with its sleepy syncopation and erotic melancholy, could have come from nowhere but Brazil. Still, Cantuária was now making his home in America. That allowed him to recruit a dream team of session players, including Bill Frisell, Joey Baron, Michael Leonhart, Laurie Anderson, and Erik Friedlander (a gifted cellist whose undulant countermelodies recall Jaques Morelenbaum's work with Veloso).

The presence of such downtown jazz luminaries as Frisell and Baron--and the fact that Verve released the disc--might have suggested a newfangled version of Jazz Samba, the 1962 session that made Jobim a household word and Stan Getz a wealthy man. Tucumã, however, was considerably harder to classify. It was also one of the most beautiful recordings of the decade, genre be damned.

On a cut like "Amor Brasileiro," Frisell's electric guitar flickers in the background like heat lightning while Cantuária murmurs sweet nothings--which sound so much more persuasive in Portuguese!--in his lover's ear: Sigo te amando sigo querendo tudo contigo / Pode apagar a luz ("I go on loving you, I go on wanting it all with you / Turn off the light now"). Elsewhere the texture thickens, to delightful effect. "Aracajú," an impressionistic valentine to Brazil itself, begins with a fairly minimal layer of acoustic guitar and percussion. But soon enough Cantuária adds Indian wood flute and some ominous samples, which manage to suggest both a careening string section and a nasty traffic jam. "Pra Gil" combines a drowsy groove with a gorgeous cello obbligato, "Sanfona" boasts a vaguely Byrds-like 12-string hook, "Igarapé" resembles Villa-Lobos in slow motion, and... well, you get the picture. Like a good postmodernist, Cantuária borrowed from everybody. Unlike many, he repaid his debts with exquisite interest.

With its dense and delicate mix, Tucumã was very much a studio creation, a product of the auditory hothouse. Cantuaria's 2001 follow-up, Vinicius, saw him returning to a more naturalistic sound. He hadn't, to be sure, renounced his eclectic instincts: on a cut like "Ordinaria," Michael Leonhart's muted trumpet and Jenny Scheinman's violin produced a kind of airborne mood music, one part Lalo Schifrin to one part Miles Davis. And the mixture of Brad Meldau's piano with Frisell's loop-the-loops on "Nova de Sete" was a scintillating oddity.

Still, this was a more pared-down performance than its predecessor, with an extra nod to Brazilian tradition. "Quase Choro" tipped its hat to the century-old choro, however obliquely. And Cantuária revived "Ela é Carioca," a Jobim classic that remains a staple of his live shows, with his introverted gringo audiences doing their best to sing along on the chorus. Not surprisingly, Cantuária's understated vocal echoed João Gilberto's--and not surprisingly, there was a layer of Frisellian icing on the cake, just to remind us that it wasn't 1959 anymore.

To a great extent, Cantuária's two releases since then reflect his efforts to translate his studio magic into a live setting. Live: Skirball Cultural Center 8/7/03 captures his quintet on what sounds like a decent soundboard tape (the label, a tiny Santa Monica outfit called Kufala, has made a specialty out of such seat-of-the-pants recordings.) It sums up both his strengths as a live performer and a handful of weaknesses.

On the plus side, there's the formidable ensemble of Scheinman, Sergio Brandao on bass, Paulo Braga on drums, and Nanny Assis on percussion. Cantuária himself pitches in on electric guitar--a big hollow-body, hooked up to a cascade of electronic effects that would do Frisell proud. What these guys (and one gal) supply in spades are grooves, with plenty of bottom and polyrhythmic décor. On the first cut, Gilberto Gil's "Procissão," the leader teases the audience for a good six minutes, doodling with the chords over triangle-and-shaker percussion, before the band lunges in behind him. "O Nome Dela" (from Sol Na Cara) gets a similar treatment: a hushed intro followed by a percolating workout.

The caveat, however, is that a certain amount of Cantuária's subtlety gets lost in the shuffle. Just compare his version of "Vivo Isolado do Mundo" on Tucumã--gentle, unhurried, and with a piercing sadness--to the one here, where the leader kicks the tempo up a notch and leads the band through another high-energy frolic.

It feels churlish to complain about such a rollicking performance, and no fan will want to be without the Kufala release. Still, I find myself missing the emotional chiaroscuro of Cantuária's best work, and his delicacy on the nylon-string guitar, clearly banished from the concert stage. Well, the artist--or the A&R guy at Bar/None Records--must have read my mind, because his 2004 release offers a marvelous fusion of his two personae.

It feels churlish to complain about such a rollicking performance, and no fan will want to be without the Kufala release. Still, I find myself missing the emotional chiaroscuro of Cantuária's best work, and his delicacy on the nylon-string guitar, clearly banished from the concert stage. Well, the artist--or the A&R guy at Bar/None Records--must have read my mind, because his 2004 release offers a marvelous fusion of his two personae.

On Horse and Fish he employs his current touring band, with Michael Leonhart subbing for Scheinman and Paul Socolow on bass. The repertoire is mostly familiar, including four cuts that also appear the Kufala set. Yet the approach is very different. The leader breaks out his acoustic guitar for much of the session, and while the band pumps its way through such dance-floor vehicles as "Procissão” and "Cubanos Postizos," they apply a delicate touch indeed to "Quase Choro," "Perritos," or the breezy, swaying "O Barquinho." The recording is pristine, and miked so closely that Cantuária sounds like he's in your living room, or boudoir. In terms of sheer sonic delight, this may be the best thing I've heard since, well, Tucumã.

What Cantuária will do next is, of course, an open question. Will he opt for studio wizardry, or the adrenaline rush of performance, or steer a course down the middle? I'll look forward to finding out. In the meantime, he's already produced a stunning body of work, beautifully triangulating between Brazil and Brooklyn--and that, as Jobim might have said, is something profound.

CODA: I wrote this piece in 2004 for a magazine that never got off the ground. Since then Cantuária has released another CD, Silva (Hannibal), which elegantly mingles his own overdubbed guitars, percussion, vocals, and loops with a string quartet. Think of it as an acoustic spin on Sol Na Cara, with the strings and Michael Leonhart's minimalist trumpet pinch-hitting for Sakamoto's electronica. A hair less intimate than Horse and Fish, this recording does share the warmth and high-gloss finish of its predecessor. My guess is that Cantuária will opt for a more naturalistic sound on the next one, but in either guise--live wire or studio perfectionist--he remains an enchanting artist.

For starters, it alludes to that loping, rhythmic displacement that gives so much of the music its trademark propulsion. It also underlines the music's status as a magnificent hybrid--a third thing. Now, all pop music is a matter of cross-pollination. But the Brazilians have mixed and matched their influences with unusual gusto. Roughly speaking, the samba emerged from a three-way dalliance among Angolan dance (the lundu), the mazurka-inflected choro, and American show tunes. Bossa nova added a supple harmonic sense, much of it derived from 1950s-era "cool" jazz, along with Gilberto's gently percussive touch on the guitar. And these styles in turn begat the Brazilian spin on post-Beatles rock, tropicalismo, which devoured everything in its path--folk, reggae, salsa, psychedelia, Tin Pan Alley--without ever quite abandoning its indigenous roots.

For starters, it alludes to that loping, rhythmic displacement that gives so much of the music its trademark propulsion. It also underlines the music's status as a magnificent hybrid--a third thing. Now, all pop music is a matter of cross-pollination. But the Brazilians have mixed and matched their influences with unusual gusto. Roughly speaking, the samba emerged from a three-way dalliance among Angolan dance (the lundu), the mazurka-inflected choro, and American show tunes. Bossa nova added a supple harmonic sense, much of it derived from 1950s-era "cool" jazz, along with Gilberto's gently percussive touch on the guitar. And these styles in turn begat the Brazilian spin on post-Beatles rock, tropicalismo, which devoured everything in its path--folk, reggae, salsa, psychedelia, Tin Pan Alley--without ever quite abandoning its indigenous roots.The prime mover of tropicalismo, of course, was Caetano Veloso, whose dedication to boundary-busting (and left-leaning) performance earned him both a short prison term and a three-year-long exile in 1969. More than three decades later, at age 62, Veloso shows no sign of flagging. But if he ever cares to pass the torch, I'd be happy to suggest a recipient: the guitarist and singer-songwriter Vinicius Cantuária.

Born in Manaus, Brazil, Cantuária moved to Rio with his family when he was seven. After cutting his teeth with a rock band, O Terco, during the 1970s, he spent much of the next ten years performing with Veloso, mostly as a percussionist. Yet he quickly outgrew the role of the anonymous sideman. His composition "Lua E Estrella" became Veloso's biggest hit in 1981, and it's clear that the current of inspiration flowed both ways, regardless of who was topping the bill. When Cantuária released his 1996 U.S. debut, Sol Na Cara, the very first track was a collaboration with his former employer. He also continues to include such Veloso-penned gems as "Jóia" in his concerts, and to emulate the skittish poetry of his lyrics.

Yet Cantuária is very much his own man, as Sol Na Cara made clear. Released around the same time the artist relocated from Rio to Brooklyn, the recording is essentially a duet with Ryuichi Sakamoto, whose keyboard and synthesizer parts added an alluring layer of electronica to Cantuári's traditionalism.

Stripped of Sakamoto's overdubs, cuts like "Samba Da Estrela" or "O Nome Dela" might well have sounded like elegant throwbacks to João Gilberto (not such a bad thing, after all). But with Cantuária's nylon-string guitar and plaintive vocals weaving in and out of his partner's electronic adornments, the result was something very different. The banked fires of the bossa nova--where sex is so clearly implicated in every syllable that nobody really needs to be explicit about it--finally entered the digital age. The music was warm and cool, intimate and expansive. It also paved the way for such neo-bossa stars as Bebel Gilberto and Moreno Veloso, both of whom had absorbed the music quite literally at their father’s knee.

Cantuária, meanwhile, upped the ante with his next CD, Tucumã. This 1999 recording is named after a rare fruit that grows only in the Amazon basin--and the music, too, with its sleepy syncopation and erotic melancholy, could have come from nowhere but Brazil. Still, Cantuária was now making his home in America. That allowed him to recruit a dream team of session players, including Bill Frisell, Joey Baron, Michael Leonhart, Laurie Anderson, and Erik Friedlander (a gifted cellist whose undulant countermelodies recall Jaques Morelenbaum's work with Veloso).

Cantuária, meanwhile, upped the ante with his next CD, Tucumã. This 1999 recording is named after a rare fruit that grows only in the Amazon basin--and the music, too, with its sleepy syncopation and erotic melancholy, could have come from nowhere but Brazil. Still, Cantuária was now making his home in America. That allowed him to recruit a dream team of session players, including Bill Frisell, Joey Baron, Michael Leonhart, Laurie Anderson, and Erik Friedlander (a gifted cellist whose undulant countermelodies recall Jaques Morelenbaum's work with Veloso).The presence of such downtown jazz luminaries as Frisell and Baron--and the fact that Verve released the disc--might have suggested a newfangled version of Jazz Samba, the 1962 session that made Jobim a household word and Stan Getz a wealthy man. Tucumã, however, was considerably harder to classify. It was also one of the most beautiful recordings of the decade, genre be damned.

On a cut like "Amor Brasileiro," Frisell's electric guitar flickers in the background like heat lightning while Cantuária murmurs sweet nothings--which sound so much more persuasive in Portuguese!--in his lover's ear: Sigo te amando sigo querendo tudo contigo / Pode apagar a luz ("I go on loving you, I go on wanting it all with you / Turn off the light now"). Elsewhere the texture thickens, to delightful effect. "Aracajú," an impressionistic valentine to Brazil itself, begins with a fairly minimal layer of acoustic guitar and percussion. But soon enough Cantuária adds Indian wood flute and some ominous samples, which manage to suggest both a careening string section and a nasty traffic jam. "Pra Gil" combines a drowsy groove with a gorgeous cello obbligato, "Sanfona" boasts a vaguely Byrds-like 12-string hook, "Igarapé" resembles Villa-Lobos in slow motion, and... well, you get the picture. Like a good postmodernist, Cantuária borrowed from everybody. Unlike many, he repaid his debts with exquisite interest.

With its dense and delicate mix, Tucumã was very much a studio creation, a product of the auditory hothouse. Cantuaria's 2001 follow-up, Vinicius, saw him returning to a more naturalistic sound. He hadn't, to be sure, renounced his eclectic instincts: on a cut like "Ordinaria," Michael Leonhart's muted trumpet and Jenny Scheinman's violin produced a kind of airborne mood music, one part Lalo Schifrin to one part Miles Davis. And the mixture of Brad Meldau's piano with Frisell's loop-the-loops on "Nova de Sete" was a scintillating oddity.

Still, this was a more pared-down performance than its predecessor, with an extra nod to Brazilian tradition. "Quase Choro" tipped its hat to the century-old choro, however obliquely. And Cantuária revived "Ela é Carioca," a Jobim classic that remains a staple of his live shows, with his introverted gringo audiences doing their best to sing along on the chorus. Not surprisingly, Cantuária's understated vocal echoed João Gilberto's--and not surprisingly, there was a layer of Frisellian icing on the cake, just to remind us that it wasn't 1959 anymore.

To a great extent, Cantuária's two releases since then reflect his efforts to translate his studio magic into a live setting. Live: Skirball Cultural Center 8/7/03 captures his quintet on what sounds like a decent soundboard tape (the label, a tiny Santa Monica outfit called Kufala, has made a specialty out of such seat-of-the-pants recordings.) It sums up both his strengths as a live performer and a handful of weaknesses.

On the plus side, there's the formidable ensemble of Scheinman, Sergio Brandao on bass, Paulo Braga on drums, and Nanny Assis on percussion. Cantuária himself pitches in on electric guitar--a big hollow-body, hooked up to a cascade of electronic effects that would do Frisell proud. What these guys (and one gal) supply in spades are grooves, with plenty of bottom and polyrhythmic décor. On the first cut, Gilberto Gil's "Procissão," the leader teases the audience for a good six minutes, doodling with the chords over triangle-and-shaker percussion, before the band lunges in behind him. "O Nome Dela" (from Sol Na Cara) gets a similar treatment: a hushed intro followed by a percolating workout.

The caveat, however, is that a certain amount of Cantuária's subtlety gets lost in the shuffle. Just compare his version of "Vivo Isolado do Mundo" on Tucumã--gentle, unhurried, and with a piercing sadness--to the one here, where the leader kicks the tempo up a notch and leads the band through another high-energy frolic.

It feels churlish to complain about such a rollicking performance, and no fan will want to be without the Kufala release. Still, I find myself missing the emotional chiaroscuro of Cantuária's best work, and his delicacy on the nylon-string guitar, clearly banished from the concert stage. Well, the artist--or the A&R guy at Bar/None Records--must have read my mind, because his 2004 release offers a marvelous fusion of his two personae.

It feels churlish to complain about such a rollicking performance, and no fan will want to be without the Kufala release. Still, I find myself missing the emotional chiaroscuro of Cantuária's best work, and his delicacy on the nylon-string guitar, clearly banished from the concert stage. Well, the artist--or the A&R guy at Bar/None Records--must have read my mind, because his 2004 release offers a marvelous fusion of his two personae.On Horse and Fish he employs his current touring band, with Michael Leonhart subbing for Scheinman and Paul Socolow on bass. The repertoire is mostly familiar, including four cuts that also appear the Kufala set. Yet the approach is very different. The leader breaks out his acoustic guitar for much of the session, and while the band pumps its way through such dance-floor vehicles as "Procissão” and "Cubanos Postizos," they apply a delicate touch indeed to "Quase Choro," "Perritos," or the breezy, swaying "O Barquinho." The recording is pristine, and miked so closely that Cantuária sounds like he's in your living room, or boudoir. In terms of sheer sonic delight, this may be the best thing I've heard since, well, Tucumã.

What Cantuária will do next is, of course, an open question. Will he opt for studio wizardry, or the adrenaline rush of performance, or steer a course down the middle? I'll look forward to finding out. In the meantime, he's already produced a stunning body of work, beautifully triangulating between Brazil and Brooklyn--and that, as Jobim might have said, is something profound.

CODA: I wrote this piece in 2004 for a magazine that never got off the ground. Since then Cantuária has released another CD, Silva (Hannibal), which elegantly mingles his own overdubbed guitars, percussion, vocals, and loops with a string quartet. Think of it as an acoustic spin on Sol Na Cara, with the strings and Michael Leonhart's minimalist trumpet pinch-hitting for Sakamoto's electronica. A hair less intimate than Horse and Fish, this recording does share the warmth and high-gloss finish of its predecessor. My guess is that Cantuária will opt for a more naturalistic sound on the next one, but in either guise--live wire or studio perfectionist--he remains an enchanting artist.

Comments:

<< Home

It's posts like this that make me a fan, and make this more than a LitBlog! (Name-checking Lalo 'Mannix' Schifrin, however, carbon-dates both you and the readers who chuckle at the reference; still, I prefer good ole Eumir Deodato...)

Post a Comment

<< Home