Monday, April 10, 2006

HOM returns (again), Kakutaniana, The Age of Illusion, Ellington clip

Readers of HOM--an exclusive group, I admit, with its own quasi-Masonic handshake--will have noticed that things have been pretty quiet here of late. A confession: I let the blog slide, mostly in the interest of finishing the novel I've been writing since 2004. Well, I wrapped that up on Friday afternoon (hooray) and will now return to my regular broadcasting schedule. I'm hoping to post on a daily basis again. We'll see how that goes. In any case, let me begin with Ben Yagoda's piece in today's Slate about Michiko Kakutani. I knew I would have to weigh in from the moment I read the first paragraph, with Salman Rushdie's characterization of the New York Times mainstay as "a weird woman who seems to feel the need to alternately praise and spank." That sounded awfully familiar, I thought. Well, what do you know--it comes from my own 1999 interview with Rushdie. Having established this personal connection, I galloped through the ensuing paragraphs. Yagoda has some nice things to say about Kakutani. He admires her intelligence and her dedication to books. And despite her reputation as the Grinch of contemporary letters, he seems to think she's mostly reliable in her judgments. But hold on, ladies and germs. The hammer is about to fall:

Readers of HOM--an exclusive group, I admit, with its own quasi-Masonic handshake--will have noticed that things have been pretty quiet here of late. A confession: I let the blog slide, mostly in the interest of finishing the novel I've been writing since 2004. Well, I wrapped that up on Friday afternoon (hooray) and will now return to my regular broadcasting schedule. I'm hoping to post on a daily basis again. We'll see how that goes. In any case, let me begin with Ben Yagoda's piece in today's Slate about Michiko Kakutani. I knew I would have to weigh in from the moment I read the first paragraph, with Salman Rushdie's characterization of the New York Times mainstay as "a weird woman who seems to feel the need to alternately praise and spank." That sounded awfully familiar, I thought. Well, what do you know--it comes from my own 1999 interview with Rushdie. Having established this personal connection, I galloped through the ensuing paragraphs. Yagoda has some nice things to say about Kakutani. He admires her intelligence and her dedication to books. And despite her reputation as the Grinch of contemporary letters, he seems to think she's mostly reliable in her judgments. But hold on, ladies and germs. The hammer is about to fall: Kakutani is a profoundly uninteresting critic. Her main weakness is her evaluation fixation. This may seem an odd complaint--the job is called critic, after all--but in fact, whether a work is good or bad is just one of the many things to be said about it, and usually far from the most important or compelling. Great critics' bad calls are retrospectively forgiven or ignored: Pauline Kael is still read with pleasure even though no one still agrees (if anyone ever did) that Last Tango in Paris and Nashville are the cinematic equivalents of The Rite of Spring and Anna Karenina. Kakutani doesn't offer the stylistic flair, the wit, or the insight one gets from Kael and other first-rate critics; for her, the verdict is the only thing.He is, of course, correct. I would put it more baldly. Kakutani's prose is flat and forgettable, her sense of humor nearly subatomic. To be sure, there are occasional sparks--mostly of disdain--that liven up the proceedings. But Yagado has proposed exactly the right litmus test. Can you imagine curling up on the sofa in 2025 and reading a thick volume of Kakutani's criticism? Reader, I cannot. (Full disclosure: I've never been reviewed by Michiko K. And at this rate, I probably never will be--but what the hell.)

Next: I've been reading Ronald Blythe's fantastic The Age of Illusion: England in the Twenties and Thirties, 1919-1940, originally published in 1963 and reissued in paper by the Phoenix Press in 2001. It's a stellar example of a sparsely populated genre, at least in this country: the wide-angle social history, with a focus on specific, examplary figures, written by a man (or woman) of letters rather than a card-carrying academic. There are some obvious precedents by British writers, including Eminent Victorians and a great book I haven't read cover-to-cover since I was in college, George Dangerfield's The Strange Death of Liberal England. (What are the American equivalents? Can somebody help me out here? I keep thinking of To the Finland Station, but Edmund Wilson is too starry-eyed--too gullible, really--when it comes to the socialist Hit Parade.) Blythe can be tart, he can be surprisingly tolerant, but he never plays the most obnoxious card in the historian's pack: hindsight. Which is to say that he never patronizes the past, no matter how idiotic it may appear in retrospect. Here's a snippet from his chapter on T.E. Lawrence, who was lethally lionized by his fellow Britons throughout the entire period:

Next: I've been reading Ronald Blythe's fantastic The Age of Illusion: England in the Twenties and Thirties, 1919-1940, originally published in 1963 and reissued in paper by the Phoenix Press in 2001. It's a stellar example of a sparsely populated genre, at least in this country: the wide-angle social history, with a focus on specific, examplary figures, written by a man (or woman) of letters rather than a card-carrying academic. There are some obvious precedents by British writers, including Eminent Victorians and a great book I haven't read cover-to-cover since I was in college, George Dangerfield's The Strange Death of Liberal England. (What are the American equivalents? Can somebody help me out here? I keep thinking of To the Finland Station, but Edmund Wilson is too starry-eyed--too gullible, really--when it comes to the socialist Hit Parade.) Blythe can be tart, he can be surprisingly tolerant, but he never plays the most obnoxious card in the historian's pack: hindsight. Which is to say that he never patronizes the past, no matter how idiotic it may appear in retrospect. Here's a snippet from his chapter on T.E. Lawrence, who was lethally lionized by his fellow Britons throughout the entire period:They liked his indifference to fame at a time when war honors and peerages were being snatched up like bargains. They liked his looks, which were the real McCoy after the pinchbeck sheik stuff of Valentino and the burnoused Lotharios of Miss M.E. Clamp. They also like his amateurism, his "modesty" and his make-your-own-kingdoms kit. He reappeared on the scene when patriotism had become rather smudgy and before empire worship had been safely channelled off into royalty worship, which left quite a lot of emotion going begging.Finally, I promise to stop with the video clips--after I link to this one. "Satin Doll" isn't one of my favorites, although this sugary concoction by Billy Strayhorn gave Ellington one of his last jukebox hits. Yet I love watching the band in action, with that saxophonic dream team in the front row (Paul Gonsalves, Jimmy Hamilton, Johnny Hodges, Russell Procope, Harry Carney) and Ellington himself dialing the voltage up and down from his seat at the piano.

Comments:

<< Home

The only 'American' equivalent I can come up with for Blythe's 'Age of Illusion...' is Isherwood's 'Lost Years: A Memoir, 1945-1951'. Isherwood, an honorary Californian, recalls with merciless candor the numbed hedonism of the first generation to stare without goggles into the abyss...you can almost smell the wet wool skivvies and the heavy hair grease (and that's not all you smell...it would be a mistake for the squeamish heterosexual to peruse this book over lunch).

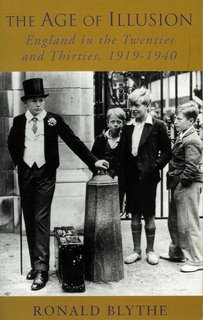

Meanwhile, your bash on Wilson's literary estrus for all things Bolshy is spot-on. Were the '30s, stunned into childishness by the mass-produced horrors of WW1, the Age of Credulity? From Wilson's *boner rouge* to Henry Miller's Theosophy to every American cultural figure of the era who fell under the spell of that huckster C.G. Jung (not to mention Isherwood's Vedanta craze)...the credulity on display definitely undermines the authorial authority. Maybe Blythe's 'The Age of Illusion' can help round out a picture of that very strange era. The cover picture is a knockout.

Post a Comment

Meanwhile, your bash on Wilson's literary estrus for all things Bolshy is spot-on. Were the '30s, stunned into childishness by the mass-produced horrors of WW1, the Age of Credulity? From Wilson's *boner rouge* to Henry Miller's Theosophy to every American cultural figure of the era who fell under the spell of that huckster C.G. Jung (not to mention Isherwood's Vedanta craze)...the credulity on display definitely undermines the authorial authority. Maybe Blythe's 'The Age of Illusion' can help round out a picture of that very strange era. The cover picture is a knockout.

<< Home