Friday, May 12, 2006

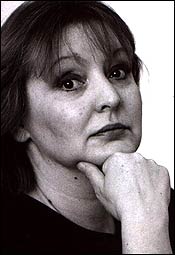

Brief Encounter: Dubravka Ugresic

Dubravka Ugresic left the former Yugoslavia in 1993, as her disintegrating homeland was engulfed in war and ethnic cleansing. She had already begun publishing fiction and essays during the previous decade. But in the wake of her move to Amsterdam, much of work--including her novel The Museum of Unconditional Surrender and a sardonic spin on the literary life, Thank You For Not Reading--has found an appreciative audience in English. Her latest novel, The Ministry of Pain, takes a fresh look at one our era's perennial topics: the trauma of exile and displacement. I began our conversation by asking her about the novel's essayistic texture.

Dubravka Ugresic left the former Yugoslavia in 1993, as her disintegrating homeland was engulfed in war and ethnic cleansing. She had already begun publishing fiction and essays during the previous decade. But in the wake of her move to Amsterdam, much of work--including her novel The Museum of Unconditional Surrender and a sardonic spin on the literary life, Thank You For Not Reading--has found an appreciative audience in English. Her latest novel, The Ministry of Pain, takes a fresh look at one our era's perennial topics: the trauma of exile and displacement. I began our conversation by asking her about the novel's essayistic texture.Dubravka Ugresic: Other people have noted the essayistic tone. Well, the novel is all about language. The narrator is an educated person, she's a teacher of literature--she's supposed to know how to be articulate. But she bears the trauma of war, and her language is fundamentally an invalid language. In many places she says: I feel like I am a student in a Croatian language course. She's appalled by how formulaic her sentences are.

James Marcus: But does that change as the novel progresses?

Ugresic: Yes, it does. The language gets richer. And then she starts dreaming: there are some surreal passages in there, and at one point she finishes a chapter inside the novel of an 18th-century Croatian author. I don't know if you remember, it's very kitschy language--

Marcus: I do recall that.

Ugresic: As the language gets richer, she becomes more free. And finally she has this realization about immigrants: they express themselves by sound rather than language. They like to shout, to scream.

Marcus: Like the two little boys who assault her with the toy knife, and then let loose with a weird, almost metaphysical howling.

Ugresic: Or adults with firecrackers. That's in the novel as well.

Marcus: Was this concept of evolving language (and also, in a sense, devolving language) present from the beginning?

Ugresic: It's hard to say. But at one point the narrator suggests that when you are traumatized, there are two possible reactions. Either you're authentically silent about it, or you talk about it, but in a mechanical way.

Marcus: Let's move on to what you call Yugonostalgia: the yearning for a country and culture that have vanished into the maw of history. Are you as afflicted with this yearning as your characters?

Marcus: Let's move on to what you call Yugonostalgia: the yearning for a country and culture that have vanished into the maw of history. Are you as afflicted with this yearning as your characters?Ugresic: Yes, I am. I've written about it elsewhere, in The Culture of Lies. The problem is that once Croatia become independent, the old, Yugoslav reality was prohibited. It is so difficult to imagine. It is like your worst nightmare. These people had to build their new identity very quickly, and from scratch, and they had to find some explanation for the war. So: "We killed in the name of our country," or, "We killed in the name of our identity." The trouble is, the Croats had only one short period of independence. That was during the Second World War, when they were a Nazi puppet state. But once they broke away in the early Nineties, they had to justify fifty years of Yugoslavism, and they behaved like bad film directors--they simply edited out everything from 1944 to 1991!

Marcus: That's a pretty dramatic splice.

Ugresic: Look, I realize the terrain is very small. I mean, who cares about Croatia? Three or four million people, that's all. But for me, it was so interesting, because I saw how you can train human beings to think differently within a year: they all change. It is a chemical reaction, as if you dipped people into some kind of acid and pulled them out again.

Marcus: With a new personality.

Ugresic: Exactly. Now they claim they saw what they didn't see, they claim to remember what they can't possibly remember, and they forget what they're even lying about. So everything is gone. Foods, for example: overnight you could no longer find a kebab in a restaurant. Why? Because kebab was considered a Serbian dish.

Marcus: So it's banished from the menu.

Ugresic: Right. Every product that had a logo or label from Belgrade--gone! Book burnings. Ethnic cleansing at the library. A new language. My poor mother had a favorite television program, and suddenly it's gone.

Marcus: So you lose everything. And the worst part is that you're supposed to pretend that it was never there in the first place.

Ugresic: The worst part is that you have this phantom pain.

Marcus: Do you go back very frequently?

Ugresic: Oh, yes. I still have family there.

Marcus: And do your trips back cause that sense of nostalgia to modulate?

Ugresic: Bit by bit, they're letting the Yugoslav era back in. But not very much. And do you know what? All that fantastic art, that subversive art, that existed during the Communist era in Hungary, Romania, the Czech Republic, and so forth—all of that is gone. Because people associate it with Communism, even though it was anti-Communist. People are so stupid.

Marcus: I went to see Orhan Pamuk kick off the festival the other night. And one of the things he talked about in his speech was the way in which the Turkish dissidents of a generation ago are now the strident nationalists of today. It reminded of a passage in The Ministry of Pain, where you write: "Perhaps that now defunct country had in fact been inhabited exclusively by victims and victimizers. Victims and victimizers who periodically changed places."

Ugresic: Well, of course this behavior is not exclusive to my country. But Croatia is a good example, you know, because it's small, it's approachable, it's like a village--

Marcus: You can see the whole picture at once.

Ugresic: That's right.

Marcus: Let me move on to the issue of translation. Has Michael Henry Heim translated all of your books?

Ugresic: Unfortunately not.

Marcus: Do you work very closely with him on the translations?

Ugresic: I don't. He's a unique person--first of all, he speaks so many languages. Second, he's an educated person, so when you mention Lili Brik in your novel, he knows exactly who that was. Michael is simply overeducated. He's fantastic.

Marcus: When I interviewed Czeslaw Milosz a few years ago, I asked whether he had ever considered transforming himself into an English-language poet. His answer: "I believe that by changing language we change our personality, and I wanted to remain faithful to the tradition in which I grew up." Could you imagine ever writing in a language other than Croatian?

Marcus: When I interviewed Czeslaw Milosz a few years ago, I asked whether he had ever considered transforming himself into an English-language poet. His answer: "I believe that by changing language we change our personality, and I wanted to remain faithful to the tradition in which I grew up." Could you imagine ever writing in a language other than Croatian?Ugresic: You know what? If I were younger, I would immediately, without hesitation, switch to writing in English. But at this point, my English would be terribly blunt--for practical reasons, I don't have time to get involved in writing in a new language. So I'm sticking with Croatian, because it's my mother tongue.

Marcus: So in your daily life you speak Dutch and English?

Ugresic: No. My Dutch is almost nonexistent.

Marcus: How long have you lived in Amsterdam?

Ugresic: I've lived in Amsterdam for a long time, but in fact I haven't arrived yet. [Laughs] I'm all the time somewhere else. I went to language class when I first moved there, but then I was in the States for six months, and by the time I returned, I had forgotten everything.

Marcus: It’s interesting to compare the playful postmodernism of Lend Me Your Character or Thank You For Not Reading with the more melancholic voice of The Ministry of Pain. Is this an evolution of style?

Ugresic: Well, the chronology is confusing. Because Thank You For Not Reading is a newer book, and one of my older books, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender, is in a darker vein.

Marcus: So we're really talking about an alternation of moods.

Ugresic: Yes. But there's another thing. I belong to that group of writers whose books are all different. I myself am bored by writing all the time the same thing. You have such writers, and some of them are very good, but it is basically one book.

Marcus: One last question, which is actually a confession. In Thank You For Not Reading, you acerbically note that the New York Times Book Review rolled out the red carpet for Ivana Trump when she published a novel: "I wouldn't have noticed it if Joseph Brodsky hadn't received in the very same issue an unjustly malicious review of his latest book Watermark. One reviewer vilified Brodsky for his language 'jammed with metaphors,' and the other praised Ivana for her analytical intelligence." Well, I was the guy who wrote the Brodsky review. It wasn't really that negative!

Ugresic: [Laughs] Well, I didn't have the review in front of me when I wrote the essay! But even it was not true, that doesn't matter--it was possible, it was believable. And it gets more believable all the time.

Comments:

<< Home

I know Dubravka carries the ID of a saucy jokester sometimes, but that last bit bothers me. I reviewed Thank You For Not Reading (http://www.playbackstl.com/classic/Current/SH/thankyou.htm) and actually mentioned those NYT reviews, as they hammered home her point. It's a little disheartening to hear that her handle on those details was less solid than I assumed it to be.

Dear James

The 13th Literature Carnival is featuring a link this post. Would you kindly link back? (It’s all about links, you know). One good way to do his is to add to your post, at the bottom: This post was featured by the Literature Carnival here. Thank you.

The management :)

The 13th Literature Carnival is featuring a link this post. Would you kindly link back? (It’s all about links, you know). One good way to do his is to add to your post, at the bottom: This post was featured by the Literature Carnival here. Thank you.

The management :)

Thank you for sharing to us.there are many person searching about that now they will find enough resources by your post.I would like to join your blog anyway so please continue sharing with us

Post a Comment

<< Home