Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Brief Encounter: Phillip Lopate

Phillip Lopate is best known for his supple and surprising essays, which have been collected most recently in Getting Personal: Selected Writings. But as far back as 1963--when he cranked out a piece about the very first New York Film Festival for his college newspaper--Lopate has been pursuing a left-handed career as a movie critic. He published a hefty sampler of this criticism nearly a decade ago, in Totally, Tragically, Tenderly. And now, casting his net considerably wider, he has assembled American Movie Critics: An Anthology From The Silents Until Now. This whopping volume should entertain and outrage film buffs across the land, even as it charts the "narrative trajectory by which the field groped its way from the province of hobbyists and amateurs to become a legitimate profession." Lopate, groping his own way through a host of promotional activities, kindly agreed to answer a few questions for House of Mirth.

Phillip Lopate is best known for his supple and surprising essays, which have been collected most recently in Getting Personal: Selected Writings. But as far back as 1963--when he cranked out a piece about the very first New York Film Festival for his college newspaper--Lopate has been pursuing a left-handed career as a movie critic. He published a hefty sampler of this criticism nearly a decade ago, in Totally, Tragically, Tenderly. And now, casting his net considerably wider, he has assembled American Movie Critics: An Anthology From The Silents Until Now. This whopping volume should entertain and outrage film buffs across the land, even as it charts the "narrative trajectory by which the field groped its way from the province of hobbyists and amateurs to become a legitimate profession." Lopate, groping his own way through a host of promotional activities, kindly agreed to answer a few questions for House of Mirth. James Marcus: Can you tell me just a little about the genesis of the book, and how you became its editor?

Phillip Lopate: The idea of the anthology was mine from the beginning. It grew out of my two previous anthologies, The Art of the Personal Essay and Writing New York, and especially the first, because I wanted to put forward film criticism as a belletristic form. I also wanted/needed an anthology like this to teach the course, and since none was available, I realized I had to do it myself, or go broke photocopying pieces for my students.

Marcus: Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Manny Farber, Pauline Kael, and Andrew Sarris occupy the upper tier of your own film-reviewing pantheon. Off the top of your head, who would be the next five, and why?

Lopate: The next five would probably be Parker Tyler, Robert Warshow, Stanley Kauffmann, Vincent Canby and Molly Haskell. Tyler is really a major, interesting critic, who could put forward ideas about gender and myth, and at the same time do very creditable, intriguing reviewing. Warshow wrote beautifully and soberly, and certainly would have been in the first rank if he lived a little longer. Kauffmann is just a marvel in terms of longevity, probity and consistency--the kind of critic I rejected when I was younger, but now am very impressed with. Canby is, as I said in my book, the best daily reviewer this country has ever had. Molly Haskell has opened up a whole area of film studies, and is very knowledgeable about film history, and writes with flexibility and amusement--in short, a delight.

Marcus: Are there any writers, or even specific pieces, that you particularly regret leaving out of the book?

Lopate: I have tons of regrets, but I should preface them by saying that I pushed hard to get the number of pages I did, and Library of America was very tolerant of my pressure, but they also have to think about things like paper costs and unit price, so that it isn't prohibitively expensive. That said, if I had had, say, a few hundred more pages to play around with, I would have liked to include: Dave Kehr, David Ansen, David Sterritt, Abraham Polonsky (he wrote a few film essays), Meyer Schapiro (nothing on the level of his art criticism, but still), Joe Morgenstern, Bosley Crowther (for perversity's sake!), Peter Bogdanovich, David Bordwell, Elizabeth Kendall, B. Ruby Rich, P. Adams Sitney, Robert Hatch, Iris Barry, David Edelstein, Louise Bogan, Arthur Knight, Archer Winsten, Herman Weinberg, James Stoller and probably a dozen more whose names escape me. At one point or another, the ones I named were all in the mix. But we ran out of room.

Marcus: Were you tempted to include a great many more "kibitzers"--that is, occasional film critics such as Edmund Wilson, Susan Sontag, and John Ashbery?

Lopate: There is no end to other kibitzers one could have included: for instance, Jack Kerouac, Donald Barthelme, Norman Mailer, Mary McCarthy... But I chose the half-dozen or so examples I thought worked best; I did not want the kibitzers to swamp the professional critics.

Marcus: In your introduction, you mentioned one criterion for inclusion that you were "almost embarrassed to admit"--ie, whether you ultimately agreed with a critic's assessment of a film. Can we assume, then, that you share Otis Ferguson's distaste for Citizen Kane, or James Agee's delight at Story of G.I. Joe (and, just to make things complicated, Manny Farber's consignment of that very same production to "the almond paste-flavored eminence of the Museum of Modern Art's film library")?

Lopate: I didn't mean I agreed with all their judgments. I think Citizen Kane is a great great movie, and I don't share Ferguson's objections, though I found them mighty interesting. I do like Story of G.I. Joe quite a lot. I am not a huge fan of Eyes Wide Shut, but I thought Jonathan Rosenbaum's evaluation of it was quite intelligent and made me want to give it another chance. In all cases, the critic touched on my own ambivalence or enthusiasm, even if I didn't necessarily share his or her final judgment in toto.

Lopate: I didn't mean I agreed with all their judgments. I think Citizen Kane is a great great movie, and I don't share Ferguson's objections, though I found them mighty interesting. I do like Story of G.I. Joe quite a lot. I am not a huge fan of Eyes Wide Shut, but I thought Jonathan Rosenbaum's evaluation of it was quite intelligent and made me want to give it another chance. In all cases, the critic touched on my own ambivalence or enthusiasm, even if I didn't necessarily share his or her final judgment in toto.Marcus: You also argue that a working film critic must develop a Philosophy of Trash--in other words, "strategies for writing about entertaining junk." Pauline Kael and J. Hoberman have been fairly eloquent on this subject. But what is your P. of T.?

Lopate: I am not a working film critic and therefore I have no need for a "philosophy of trash," nor do I have one. I am free to write about obscure art movies that touch me. Of course there are many mediocre movies that I can watch with a certain degree of pleasure, especially if I am tired and viewing them on TV.

Marcus: You quote John Simon as to the reviewer's traditionally low spot on the totem pole: "Reviewing is something that newspaper editors have invented: it stems from the notion that the critic is someone who must see with the eyes of the Average Man or Typical Reader (whoever that is) and predict for his fellows what their reaction will be. To this end, the newspapers carefully screen their reviewers to be representative common men, say, former obituary writers or mailroom clerks, anything but trained specialists." Factoring in a grain of Simon-style spleen, was he correct then? Is he correct now?

Lopate: I do think that in the past newspapers and magazines tended to assign writers to the movie post without particular regard for how much they knew about the medium, and with an eye toward mirroring the common reader. That's less true now, partly because of the emergence of graduate film studies programs, which spew out many qualified young people with a knowledge of film history. Most daily reviewers continue to adopt a chummy, I'm-like-you pose toward their audience, but not all. For instance, Manohla Dargis doesn't; she wears her cine-knowledge proudly.

Marcus: Some of the critics here gravitate toward High Art, others toward expedient craftsmen, who (in Manny Farber's words) "spring the leanest, shrewdest, sprightliest notes from material that looks like junk." In the post-studio age, is this still a valid or useful distinction? Looking at the current scene, who's our preeminent High Art guy (or gal)? Who are the killer craftsmen?

Lopate: I doubt that the High Art/expedient craftsman distinction makes much sense in an age when the studio system no longer functions, and every schlockmeister considers himself an auteur, with the right to include a title that says "A film by Joe Dokes." We know who the High Art types are: Wes Anderson, Atom Egoyan, Hal Hartley, Charles Burnett, Noah Baumbach, for starters. Michael Mann is a killer craftsman who presents himself as a semi-high art auteur, a perfect example of the current confusion. Spielberg is in a league of his own as a great craftsman who wants to be considered a great artist (and sometimes is). There are craftsmanlike directors such as Joe Rubin, Amy Heckerling, John Carpenter, Wes Craven, Joe Dante, John Woo, who almost always turn out well-made films. Someone like Curtis Hanson is also right on the cusp.

Marcus: I was struck by Jonas Mekas's take on A Hard Day's Night: "Art exists. Aesthetic experience exists. A Hard Day's Night has nothing to do with it. At best, it is fun. But 'fun' is not an aesthetic experience: Fun remains on the surface. I have nothing against the surface. But it belongs where it is and shouldn't be taken for anything else." Substitute "pleasure" for "fun," I would suggest, and his whole argument goes up in smoke. But what do you think? (This isn't ultimately a question about Mekas, of course, but about sensual versus cerebral pleasures. Assuming the two can truly be separated.)

Marcus: I was struck by Jonas Mekas's take on A Hard Day's Night: "Art exists. Aesthetic experience exists. A Hard Day's Night has nothing to do with it. At best, it is fun. But 'fun' is not an aesthetic experience: Fun remains on the surface. I have nothing against the surface. But it belongs where it is and shouldn't be taken for anything else." Substitute "pleasure" for "fun," I would suggest, and his whole argument goes up in smoke. But what do you think? (This isn't ultimately a question about Mekas, of course, but about sensual versus cerebral pleasures. Assuming the two can truly be separated.)Lopate: You cannot substitute "pleasure" for "fun," they are two entirely different notions. I thought Mekas was brave and intelligent and precise in using the word "fun" to define A Hard Day's Night, and I think he was reacting in part to the over-praise of Richard Lester, by Sarris, among other critics who were grateful to enjoy a youth movie and feel hip. Art requires complexity, not cozy complacency, and many of the youth-culture assumptions that underlay A Hard Day's Night refused complexity. As for some distinction between sensual and cerebral pleasures, I don't see how you can draw a hard and fast line, but both or either have to promote a sense of rich complexity for a movie to be considered art.

Labels: A Hard Day's Night, Manny Farber, movies, Phillip Lopate

Sunday, March 12, 2006

Thank god for the Internet

Because it's all about me, II

The Chinese version of Amazonia has just came out, courtesy of the fine folks at Bookery Publishing. The jacket features of a burst of holy light emanating from a window, along with some sentences from the widely reviled Emerson chapter of the book. If that's what it takes to put this baby on the Chinese bestseller list, then I'm all for it. Meanwhile, the German edition is due out next week from Schwarzerfreitag. The translator, Andreas Freitag, spent a year or so in Seattle during the Boom, which should give him an excellent purchase on that era's pie-in-the-sky atmospherics. He also runs the publishing house, oversees a small gallery space, and has brought out a quirky little collection of found Polaroid photographs. Give this man a hand!

The Chinese version of Amazonia has just came out, courtesy of the fine folks at Bookery Publishing. The jacket features of a burst of holy light emanating from a window, along with some sentences from the widely reviled Emerson chapter of the book. If that's what it takes to put this baby on the Chinese bestseller list, then I'm all for it. Meanwhile, the German edition is due out next week from Schwarzerfreitag. The translator, Andreas Freitag, spent a year or so in Seattle during the Boom, which should give him an excellent purchase on that era's pie-in-the-sky atmospherics. He also runs the publishing house, oversees a small gallery space, and has brought out a quirky little collection of found Polaroid photographs. Give this man a hand!Wednesday, March 08, 2006

Something is rotten in Bucharest

Decebal (86-107 AD), in case you were wondering, was the ruler of Dacia, who fought off two fierce incursions by the Romans before his kingdom was absorbed into Trajan's empire. His lower lip, at least, does look fairly sensual in this carving. But that's not the point, is it?There appeared either history books that insisted on Decebal's sensual lips or the unmistakable hairdo of Andreea Esca or geography books in which the height of the Carpathians appeared with different altitudes. In recent years, during the auctions for the textbooks, the prices crushed the content. The Education Ministry, always with its pockets empty, encouraged the acquiring of manuals at toilet paper prices. Like price, like quality: poor print, unattractive illustrations, anonymous authors.

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

Golden codgers

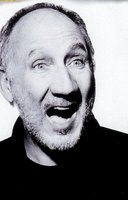

"Hope I die before I get old," declared The Who's Pete Townshend in 1965, and certainly there have been times, during his drink-and-drug-addled middle decades, when he seemed determined to fulfill this youthful prophecy. Yet Townshend, along with a good many of his rock-and-roll peers, has survived into ripe old age. Some, like the Rolling Stones, have turned into glorified oldies acts. But a handful--like Donald Fagen (ex-Steely Dan) and Ray Davies (ex-Kinks)--may actually be poised to do some of their best work.

To read the rest, click here. And let me continue with a quote from Townshend himself, who recently gave a rare interview to Mojo, sounding very peppy and looking like distinguished gent with a hilarious secret of some kind. The interviewer, Pat Gilbert, asks the 60-year-old Townshend whether the Who can still make "a classic rock record." His answer:

To read the rest, click here. And let me continue with a quote from Townshend himself, who recently gave a rare interview to Mojo, sounding very peppy and looking like distinguished gent with a hilarious secret of some kind. The interviewer, Pat Gilbert, asks the 60-year-old Townshend whether the Who can still make "a classic rock record." His answer:We could, couldn't we? I mean we could do a White Stripes, I could sit with a drummer and just play electric guitar and I know it would be spectacular, because I play the most fantastic electric guitar.Great idea! Bag the synthesizers! Back to mono! I'm going to conclude with a bit from Roger Daltrey, who also answered a few questions, touching at several points on the old hope-I-die-before-I-get-old conundrum. What were his feelings about John Entwistle, the band's virtuoso bassist who died, in flagrante and with a generous pinch of cocaine in his system, in June 2002?

John was very happy being John. It wouldn't have been what I would have done with my life, but he was always there when you needed him, and he was harmless to everyone else. You couldn't have changed him. We didn't call him the Ox for nothing. Two hookers, two lines of coke...and a heart attack. Better than the slow, smelly alternative.Gather ye rosebuds, etc. You've got to love these guys.

Friday, March 03, 2006

NBCC panel: Just the facts, M'am

Miller began with Tanenhaus, whose stubble and consistently creased forehead gave him a Don-Johnson-at-grad-school look. Her question: in the wake of so many memoir-related scandals, was the Book Review changing the way it handled such books? "In a word," he replied, "no. Obviously it's a fraught subject. And particularly in the case of James Frey, people want to know why we're still listing his book as nonfiction."

Good point, given the author's carefully documented Munchausen tendencies. But Tanenhaus insisted that the memoir has always been on slippery ground when it comes to verifiable truth. "We begin with the presumption that a memoir is artificial. It's very much a contrived form," he argued, enlisting that notorious fibber St. Augustine to prove his point. And if we're to believe his argument, the distinction is getting blurrier by the day. "What used to be the novel has migrated into the memoir," he said, and essentially suggested that we throw in the towel on this puppy. "If we didn't pretend that the factual value of a memoir is so great, then we wouldn't have this confusion in the first place." (He did add that the Book Review would "look more deeply into an author's history" if the book was billed as a "confessional memoir"--but aren't they all?--and cited Tony Hendra's controversial Father Joe as an example.)

Now Kathryn Harrison addressed herself more specifically to the Frey Affair, and had some hard words for Oprah's favorite whipping boy. "He himself described the book as self-mythologizing," she recalled. "But real memoir seeks to demythologize the subject. Rather than sustaining the author's narcissism, it's supposed to disrupt that beautiful image in the water."

And how did the whole mess look to Betsy Lerner, a literary agent who is herself a former memoirist and book editor? She drew a fairly sharp line between art and commerce, while conceding that she's danced around it throughout her career: "When I was an editor, I felt that I was on the side of the angels. But once I crossed over to the dark side...well, publishing books is a business, and people buy them, and we all have to pay our rent." But did she ever handle an author whose memoir seemed to cry out for third-party substantiation? "I've worked with some great embroiderers in my day," she allowed.

Lerner also invoked a litmus test that the other participants endorsed, at least in principle: the "ring of truth" you can sense in an authentic text. Putting aside the sheer subjectivity of the whole thing--what sounds like Big Ben to me might register for you as the weenie tintinnabulation of a cheap travel clock--this seems to suggest that facts don't matter in the least. Perhaps that's why Miller now attempted to firm up the rules a little bit. What about Binjamin Wilkomirski's Fragments, a 1995 concentration-camp memoir whose author turned out to have spent the war years in Switzerland? Wasn't that, as she suggested, "beyond the pale?"

At this point Vivian Gornick rode into battle on Wilkomirski's behalf. "A hybrid form is now coming into being," she said. And in this form--let's call it the Memoir Nouveau--the narrator is obliged to be reliable, but not factual. Hmm. She cited Thomas DeQuincey's Confessions of an Opium-Eater as a classic example: the patron saint of stoners relentlessly deviated from the facts, yet he is "telling a true story, getting to the bottom of an experience."

Harrison seconded Gornick's argument: "You can tell when a piece of writing is true, whether it's officially fiction or memoir." An apprentice epistemologist could have a field day with this statement--indeed, with the entire discussion, which is why it was so damn interesting--but now Tanenhaus made a broader cultural argument about the audience for memoirs like Frey's. "Non-readers give tremendous authority to the written word," he said, tracing his point back to Christopher Lasch, and suggested that they felt a correspondingly sharper sense of betrayal. Nor was it autobiographers alone who were now seen as fakers: "Some of the furor surrounding Frey's memoir is rooted in a pervasive suspicion of writers, reporters, and supposed tellers of the truth. There's a bigger issue kicking around--a perception that people in authority don't behave honestly."

Fight the power, Sam! But don't forget to stick it to the real villains here: the fact-checkers. "I think we now live in the age of the tyranny of the fact-checker," he noted. "There's a certain kind of writing you can't verify, though it makes very direct assertions about the culture." A figure like Dwight Macdonald--with tremendous intellectual antennae but little appetite for factual spadework--would be effectively shut out of our literary culture, Tanenhaus concluded.

Now the audience, which seemed a little restive at this auto-da-fe of factuality, began asking questions. And to nobody's surprise, the Frey Affair kept popping back up to the surface. One audience member asked whether the New York Times hadn't stoked the flames of the scandal by according it so much coverage. Tanenhaus replied: "I barely took an interest in this. I haven't read the book, and have no interest in reading it. I hardly even read our coverage of it."

But it was Harrison who drew the most memorable distinction between fiction and fact. Quizzed about the relationship between her autobiographical novel, Thicker Than Water, and The Kiss, a controversial memoir that came directly on its heels, she recalled: "I wrote the story of my family as a novel, and I did the best I could. But as soon as that novel was published, I felt that I had betrayed my material by saying, in effect, that incest didn't happen. I was propping up a societal lie. I was horrified." So she promptly produced a memoir telling the same story, minus the fictional trimmings and mussed trail that are every novelist's privilege. Here, at least, she seemed to be arguing that facts mattered a great deal after all--that the implicit contract between the memoirist and the reader was what gave The Kiss its revelatory firepower.

Not that Harrison's problems ended there. As another audience member pointed out, she was then pilloried for airing her family's dirty laundry without the face-saving mediation of fiction. "That's a testimony to the power of taboo," Harrison explained, with a trace of fatigue. "It's still alive and well out there."

UPDATE: William Logan won for The Undiscovered Country! As did E.L. Doctorow (The March), Svetlana Alexievich (Voices from Chernobyl), Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin (American Prometheus), Francine du Plessix Gray (Them), and Jack Gilbert (Refusing Heaven). Congratulations all around. For an extra soupcon of detail, you can read the AP dispatch here.

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

A few notes: Fagen, Atwood, Burroughs

While voters get the politicians they deserve, bands can attract audiences they don't always expect. "When Steely Dan started out, we had a more normative band... So our fans were the usual bunch of psychos, just normal rock fans. The sort of psychos we have now are a much higher class of people." A wry tone creeps into Fagen's voice. "A lot of dentists. Every time I go to the dentist in any city, they've always got plenty of Steely Dan records to play while they're drilling your teeth and producing pain. Whole dental colleges run on Steely Dan music."Next, Margaret Atwood's goofy book-signing apparatus, which will be officially unveiled this Sunday in London. For a long time I assumed this whole business was a joke--the author's deadpan response to a bad case of Autographer's Wrist. But no, she's deadly serious, according to this piece by Angela Pacienza:

Oh, wait--I forgot about the hockey stick. I take it all back. This could be the greatest thing since the first Segway rolled off the assembly line.Here's how it works: The author scribbles a message using a stylus pen on a computer tablet. On the receiving end, in another city, a robotic arm fitted with a regular pen signs the book. The author and fan chat via webcam.

Created with book tours in mind, the machine has several other potential applications: enhancing credit card security, allowing doctors to write prescriptions for out-of-town patients, and signing legal forms such as divorce or real-estate documents from another province. The LongPen is also adaptable to hold CDs and hockey sticks, allowing music and sport stars to give autographs remotely.

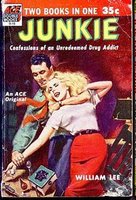

Finally, the New York Public Library has acquired the compendious and no doubt icky archive of William S. Burroughs, including "draft versions of his most famous work, Naked Lunch, along with other manuscripts and letters that range from the early 1950s to the early 1970s." The AP dispatch is mum on what else might be tucked away in there--snapshots of his cats? leftover Benzedrine?--but somebody is going to have a very interesting time assembling the catalogue. Meanwhile, feast your eyes on this pulpy edition of Junky, ascribed to one "William Lee," whose addictive habits seem to be getting in the way of his personal life. (Update: Edward Wyatt's article in today's New York Times does indeed include more info about the contents of the Burroughs Archive. It also makes clear that the author intended this vast accumulation of letters, manuscripts, photographs, and taped interviews to be regarded as a work of art unto itself, not simply as a scrapbook-cum-compost heap.)

Finally, the New York Public Library has acquired the compendious and no doubt icky archive of William S. Burroughs, including "draft versions of his most famous work, Naked Lunch, along with other manuscripts and letters that range from the early 1950s to the early 1970s." The AP dispatch is mum on what else might be tucked away in there--snapshots of his cats? leftover Benzedrine?--but somebody is going to have a very interesting time assembling the catalogue. Meanwhile, feast your eyes on this pulpy edition of Junky, ascribed to one "William Lee," whose addictive habits seem to be getting in the way of his personal life. (Update: Edward Wyatt's article in today's New York Times does indeed include more info about the contents of the Burroughs Archive. It also makes clear that the author intended this vast accumulation of letters, manuscripts, photographs, and taped interviews to be regarded as a work of art unto itself, not simply as a scrapbook-cum-compost heap.)