Tuesday, January 31, 2006

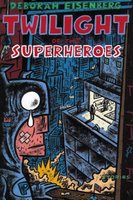

Twilight of the Superheroes

I've been a fan of Deborah Eisenberg's fiction for many years. Her detractors have sometimes complained about her focus on Manhattan-style angst, as if she were some kind of Woody Allen in drag, and overlooked the alternating currents of satire and tenderness that give her stories their peculiar glow. In any case, Eisenberg has a new collection out, her first in nearly a decade: Twilight of the Superheroes. It is, I confess, something of a mixed bag. In the title story, a fictional grapple with 9/11, the author stubs her toe on the generational divide: the older characters live and breathe, while a quartet of twentysomethings seems to have walked in off the set of Friends. Eisenberg manages the voice of (relative) youth to better effect in "Revenge of the Dinosaurs." I also admired the grief-stricken telegraphy of "Like It Or Not," very much in the author's classic New Yorker groove.

I've been a fan of Deborah Eisenberg's fiction for many years. Her detractors have sometimes complained about her focus on Manhattan-style angst, as if she were some kind of Woody Allen in drag, and overlooked the alternating currents of satire and tenderness that give her stories their peculiar glow. In any case, Eisenberg has a new collection out, her first in nearly a decade: Twilight of the Superheroes. It is, I confess, something of a mixed bag. In the title story, a fictional grapple with 9/11, the author stubs her toe on the generational divide: the older characters live and breathe, while a quartet of twentysomethings seems to have walked in off the set of Friends. Eisenberg manages the voice of (relative) youth to better effect in "Revenge of the Dinosaurs." I also admired the grief-stricken telegraphy of "Like It Or Not," very much in the author's classic New Yorker groove.There is, however, one absolute gem in the book, "Some Other, Better Otto." It's a tale of familial dysfunction, always an Eisenbergian speciality, and she gets some wonderful comic mileage out of that perennial war of the worlds:

The older one even had a wife, whom Corinne treated with a stricken, fluttery deference as if she were a suitcase full of weapons-grade plutonium. The younger one was restlessly on his own. When, early in the evening the three stood and announced to Corinne with thuggish placidity that they were about to leave ("I'm afraid we've got to shove off now, Ma"), Otto jumped to his feet. As he allowed his hand to be crushed, he felt the relief of a mayor watching an occupying power depart his city.Love it! But what I loved even more was an observation Otto makes about his sister, a chronic depressive with the leapfrogging intuitive powers of a genius. Otto keeps trying to put his finger on exactly what makes her different. Finally he comes up with an answer:

A tremendous capacity for metaphor, Otto assumed it was; a tremendous sensitivity to the deep structures of the universe. Uncanny. It seemed no more likely that there would be human beings thus equipped than human beings born with satellite dishes growing out of their heads.The author, too, is one of those uncanny human beings. Without that identical gift, she would still be a superb comedian and anthropologist of middle-class moeurs. But metaphor is what ultimately allows a naturalist like Eisenberg to plunge beneath the parochial surface and find the real treasures, the real truths. For that we should be grateful. In literature, as in life, superheroes are in short supply.