Thursday, July 28, 2005

Primo, short stuff

On the basis of several glowing reviews, including Terry Teachout's notice in the Wall Street Journal--and because I've been fascinated by Primo Levi's work for more than two decades--I took in a performance of Antony Sher's Primo last night at the Music Box Theater. I gather that the South African-born actor negotiated with Levi's estate for several years before they gave the nod to his adaptation of If This Is A Man. To Sher's credit, he has stayed true to the lucid, low-key splendor of the original text (meaning the English translation made by Stuart Woolf, under Levi's whiskey-fueled supervision, in 1958.) The set--three concrete slabs, one doorway, one chair--is appropriately minimal. The sound design and lighting are unobtrusive. And Sher himself consistently underplays. His narration is so even, so tightly controlled, that when he puts some extra English on certain phrases--"interminable black pine forests"--it qualifies as a dramatic event. So too does the moment when he rolls up his sleeves, or replaces his glasses, a gesture carefully timed to coincide with his liberation by the Russians.

On the basis of several glowing reviews, including Terry Teachout's notice in the Wall Street Journal--and because I've been fascinated by Primo Levi's work for more than two decades--I took in a performance of Antony Sher's Primo last night at the Music Box Theater. I gather that the South African-born actor negotiated with Levi's estate for several years before they gave the nod to his adaptation of If This Is A Man. To Sher's credit, he has stayed true to the lucid, low-key splendor of the original text (meaning the English translation made by Stuart Woolf, under Levi's whiskey-fueled supervision, in 1958.) The set--three concrete slabs, one doorway, one chair--is appropriately minimal. The sound design and lighting are unobtrusive. And Sher himself consistently underplays. His narration is so even, so tightly controlled, that when he puts some extra English on certain phrases--"interminable black pine forests"--it qualifies as a dramatic event. So too does the moment when he rolls up his sleeves, or replaces his glasses, a gesture carefully timed to coincide with his liberation by the Russians.Three or four times, Sher does ratchet up the intensity. And in one case, he actually falls short of Levi's true level of outrage, due to a mistake in Woolf's translation. On the heels of a "selection"--the periodic harrowing of the camp population by the SS--Levi observes a fellow prisoner sending up a prayer of thanks to God for sparing him. Repelled, he writes: Se fossi Dio, sputerei a terra la preghiera di Kuhn. Meaning: "If I were God, I would spit out Kuhn's prayer on the ground." Woolf puts a slightly milder spin on this expression of metaphysical disgust: "If I was God, I would spit at Kuhn's prayer." (For this insight, a tip of the hat to Risa Sodi's essay in Memory and Mastery: Primo Levi as Writer and Witness, published by SUNY Press in 2001.)

A minor flaw, of course. But Sher's fealty to his source material does have some problematic consequences. Agreed: any attempt to juice up Levi's tale, to make it more boldly theatrical, would be an absolute betrayal of the original book. But this is a work of drama, after all, which is ultimately hobbled by Sher's anti-dramatic mandate. What's left is an expert, empathetic, but lukewarm creation. If Levi's book had never been published--if it hadn't already taken its place as one of the primary texts of the last, sanguinary century--I surely would have found Primo more riveting. Having read If This Is A Man, I found it sadly superfluous: Auschwitz Lite. (A final affront: having adjourned with my companions to a nearby bar for a post-theater drink, we had to listen to Sting sing "King of Pain" on the jukebox. Definitely not a good chaser after an evening of Primo Levi.)

On a very different note: brevity is the new black. According to a piece in the Western Mail (via Literary Saloon), Leaf Publishing--a spinoff of the University of Glamorgan in Wales--is launching a series of bite-sized books called A6. Each volume will run to about 4,000 words, and is meant to be devoured in a single sitting. The series will include both fiction and nonfiction, color-coded by genre. (No details about what color goes with what genre. But it was Flaubert, let's recall, who said: "I want to write a novel about the color gray.") Meanwhile, Amazon has launched its Amazon Shorts program: brief stories or essays by name-brand (for the most part) authors, sold excusively as HTML downloads for 49 cents a pop. I came across the program via Publishers Lunch, and it may not be quite ready for prime time, given the difficulty of finding it on the site. In any case, there seem to be a few remaining kinks in the digital pipeline. When I clicked through to the Nonfiction Shorts page, I got the following message: "We're sorry. We are currently out of these items." Somebody better check the virtual inventory, no?

Wednesday, July 27, 2005

Love (letters) for sale

a piece of paper with Aniston's name and phone number written in lipstick, a love letter from Aniston handwritten in red pen, a note written on toilet paper with birthday wishes from Aniston to Baroni on his 17th birthday, a page from Baroni's little black book containing Aniston's contact information, a photo of the pair hugging when they first met in 1974, an autographed photo from the cast of "Friends," a December 2004 copy of In Touch magazine with an article about their relationship and a notarized statement by Baroni certifying and attesting to the authenticity of the materials.If you take a peek at the eBay site, there seem to be two bids, both retracted, plus a fair amount of ridicule from fellow customers. Yet I suppose some lucky bidder may still extract these latter-day Aspern Papers from the seller--and who knows, perhaps he has an entire roll of billets-doux.

Tuesday, July 26, 2005

Harry Potter, sacred cow

When somebody e-mails to say, "Seriously bitch u need to watch what teh fuck you say," it certainly commandeers a critic's attention. Add to that the dozens of correspondents who took the trouble to call me dork, idiot, schmuck or worse, and it's all occasioned some serious soul-searching here on the literature desk.Kipen is actually quite gracious about the whole affair, answering some of his correspondents' gripes and commending a critique by his 10-year-old niece. He also asks: "Is this degree of protective devotion some form of mass hysteria, or a hopeful development in otherwise unreaderly times?" I'd opt for the former, myself. Surely J.K. Rowling, the most successful author of the modern era, can handle an occasional nicker of negativity (that sounds like Spiro Agnew, doesn't it?). Even Harold Bloom, who's been fighting a one-man battle against Pottermania for some time, concedes that there's no point in complaining. “Protesting Harry Potter is like standing in front of the Atlantic Ocean," he said during an interview last year. "It’s ridiculous, you haven’t got a chance.” Which hasn't stopped Bloom, or Kipen, from trying.

More on Pamuk

To some degree, we all worry about what foreigners and strangers think of us. But if anxiety brings us pain or clouds our relationship with reality, becoming more important than reality itself, this is a problem. My interest in how my city looks to western eyes is--as for most Istanbullus--very troubled; like all other Istanbul writers with one eye always on the West, I sometimes suffer in confusion.Pamuk alludes several times to a quasi-musical structure undergirding the book, which I haven't yet detected. But the perceptual confusion he mentions in the preceding paragraph is what the book is about. How does the East look to the West--and vice-versa? At one point, describing Flaubert's five-week sojourn to Istanbul in 1850, Pamuk parenthetically notes that the traveller planned to write "a novel called 'Harel Bey,' in which a civilized Westerner and an eastern barbarian slowly come to resemble each other, finally changing places." Flaubert never wrote it. But Pamuk did, in his fourth novel The White Castle, which involves exactly this sort of cultural mating dance, culminating in a swap of identities. Tricky devil, isn't he?

As for the translation by Maureen Freely, Pamuk is rumored to like it so much that he's asked her to re-translate some of his earlier work, including The Black Book. Not knowing Turkish, I can't attest to its accuracy, but the prose is attractively unruffled, with only an occasional, non-idiomatic dimple. Plus one notable blooper, I'm afraid. Regarding Joseph Brodsky's famous swipe at the deplorable East, "Flight from Byzantium," we read: "Perhaps because he was still smarting from W.H. Auden's brutal review of the book recounting his journey to Iceland, Brodsky began with a long list of reasons he'd come to Istanbul (by plane)." Whoopsie. Unless I'm very wrong, Freely has misunderstood one of Pamuk's simit-shaped sentences. It was Auden who wrote a book about his journey to Iceland--his collaboration with Louis MacNeice, Letters from Iceland, was published in 1936. Was Brodsky smarting from the negative reviews that Auden had gotten nearly fifty years before? I suppose that's possible. But that's not what the sentence says.

All for now, except to mention that during my five-hour drive from New Hampshire on Sunday, I slipped a disc by an Istanbul-based rapper named Ceza into the CD player, and what do you know--I liked it. I didn't understand a single syllable, of course, although on one cut I'm sure I heard the words Jack Benny popping out of the mix. But the guy is a gifted motormouth, spitting out five umlaut-ornamented words per second, and he's clearly got what we English speakers call an attitude: perhaps I stumbled across the Turkish Eminem. A marketing hook to die for?

Labels: Auden, Istanbul, Joseph Brodsky, Orhan Pamuk, Turkey

Friday, July 22, 2005

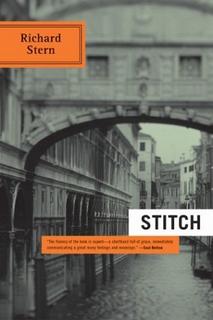

STITCH, cut-rate Potter, Polanski, Ashbery

Anyway, one of the things that kept me going during my interludes of consciousness was Richard Stern's STITCH, part of an excellent reissue program from Northwestern University Press. Festooned with the sort of blurbs that most writers would die for--"brilliant," says John Cheever, as opposed to "beautifully damn good" (Howard Nemerov) or "superb" (Saul Bellow) or "[among] my favorite two postwar novels" (John Berryman)--this is early Stern, first published in 1965. The author's evocation of postwar Venice is a major accomplishment. His portrait of the sublimely cantankerous Ezra Pound is even more impressive. Now, it happens that Stern encountered Pound in Venice during this very period, and his brief recollection (reprinted in One Person and Another) is wonderfully vivid:

Anyway, one of the things that kept me going during my interludes of consciousness was Richard Stern's STITCH, part of an excellent reissue program from Northwestern University Press. Festooned with the sort of blurbs that most writers would die for--"brilliant," says John Cheever, as opposed to "beautifully damn good" (Howard Nemerov) or "superb" (Saul Bellow) or "[among] my favorite two postwar novels" (John Berryman)--this is early Stern, first published in 1965. The author's evocation of postwar Venice is a major accomplishment. His portrait of the sublimely cantankerous Ezra Pound is even more impressive. Now, it happens that Stern encountered Pound in Venice during this very period, and his brief recollection (reprinted in One Person and Another) is wonderfully vivid:Pound was flat on the bed, a blanket to his chin. The face was thinner, the beard sparser than my expectations, the face lined like no one else's, not the terrible morbid furrows of Auden, not the haphazard crevices of so many benign elders. For me, at least, these lines had the signatory look of individual engagements. Brow and cheeks, arcs and cross-hatches, with spars of eyebrow and beard curling out from what the sculptors worked with, the grand ovoid, the looping nasal triangle.That final sentence points straight to the author's strategem in STITCH: he transforms the epic and erratic poet into an epic and erratic sculptor. Like his real-life model, Thaddeus Stitch has descended into an anti-Semitic lather during the Second World War, and earned himself a long stretch in a jail cell. (The dicey issue of Pound's sanity, and his residence at St. Elizabeths, has been left out of the picture.) Now a free man, too feeble to work and too guilty to savor his retirement, he crosses the path of two artistically-inclined young Americans in Venice. Innocence does its fender-bending thing with experience, as it inevitably must. I won't give away the plot, but suffice it to say that the perfection of life and the perfection of art are both in short supply. Run, don't walk, to the bookstore and pick up these reissues. Also, keep an eye peeled for a Brief Encounter with Richard Stern, which should appear on HOM during the next couple of weeks.

Meanwhile (according to the Scotsman), a Parliamentary firestorm is underway regarding the most pressing issue of our time: discounted pricing of the new Harry Potter book. Labour MP Lynne Jones declares: "I note that copies of Harry Potter And The Half Blood Prince are selling in supermarkets for as little as £4.99 compared with the trade price for lower volume outlets of £10.70 and the retail price of £16.99." Not exactly Churchillian, is it? To be fair, Jones is concerned for the viability of small bookstores, an issue close to my own heart. But I'm afraid this horse left the barn a long time ago. Consumers expect deep discounting and will turn away in droves if they don't get it. On a cheerier note, ten other MPs have put forth a declaration defending J.K. Rowling against the Pope's doctrinaire spitballs. Hooray. We must take our good news where we can find it.

I'm sure that's what Roman Polanski is thinking, anyway. The pint-size Pole has just won his defamation suit against Vanity Fair. I haven't been following the case very closely--and God knows that Polanski has committed his share of sexual misdemeanors over the years--but it brought to mind the related material in the Dino de Laurentiis bio I translated in 2002. Some fascinating facts: De Laurentiis originally wanted Polanski to direct his goofy 1976 remake of King Kong. The mind boggles, does it not? Jessica Lange, a giant mechanical monkey, and Roman Polanski at the helm? Anyway, the Italian version of the book also stipulated that De Laurentiis was the last person the director visited before fleeing the country in 1978. According to Dino, in fact, he dipped into the petty-cash drawer to fund Polanski's airplane ticket. True or not, this stuff has been expunged from the American edition.

Finally, I picked up The Double Dream of Spring the other day, thinking I might have a refreshing dip in Ashbery's swift-running stream of consciousness. I wasn't in the mood. I didn't feel like letting my free-associative hair down. However, I did latch onto this final stanza from "It Was Raining in the Capital," more morbid and balladic than is Ashbery's wont:

The sun came out in the capital

Just before it set.

The lovely death's head shone in the sky

As though these two had never met.

Wednesday, July 20, 2005

Two Kodak moments

These are whirling dervishes of the Mevlevi Brotherhood, attaining God via rotation. It was an amazing spectacle, not the least because it was so contained--I expected a noisy climax, and got serenity instead. The dervishes spin by, men and women both, mostly with their eyes closed, having already shed the black cloaks that symbolize earthly attachment. Their faces look calm. The dance takes place in an octogonal space, and the outer gallery is packed with camera-toting gawkers from the West, us included, which raises some interesting questions about ecstatic ritual versus performance. Which is it? Both? In any case, the tall hat, called a sikke, is supposed to be the "tombstone of the ego." A sad fact: in my case, it would have to be at least twenty to thirty feet high.

These are whirling dervishes of the Mevlevi Brotherhood, attaining God via rotation. It was an amazing spectacle, not the least because it was so contained--I expected a noisy climax, and got serenity instead. The dervishes spin by, men and women both, mostly with their eyes closed, having already shed the black cloaks that symbolize earthly attachment. Their faces look calm. The dance takes place in an octogonal space, and the outer gallery is packed with camera-toting gawkers from the West, us included, which raises some interesting questions about ecstatic ritual versus performance. Which is it? Both? In any case, the tall hat, called a sikke, is supposed to be the "tombstone of the ego." A sad fact: in my case, it would have to be at least twenty to thirty feet high. Here's Nina, feeling no pain. She had spent part of the previous week hunkered down in a Turkish Internet cafe, finishing an article on data visualization and wrassling with the counterintuitive (to an American) layout of the computer keyboard. And now? We're all sitting on the Galata Bridge, watching the sun set on the other side of the Golden Horn, bathed in a honey-colored light that my ratty digital camera failed to capture. The conical shape to the right of her head is the distant Galata Tower, right next door to our hotel. Due to a fluke we got the absurdly fancy suite on the top floor, outfitted with every conceivable amenity except for hot water. Hence the bracing, chilly sponge baths and my reluctance to shave. Aside from that it was perfect, and the views of the adjacent tower--built in 1348 by the Genoese, now housing a dreary nightclub with steamtable food--made me forget the hot-water problem for literally minutes at a time.

Here's Nina, feeling no pain. She had spent part of the previous week hunkered down in a Turkish Internet cafe, finishing an article on data visualization and wrassling with the counterintuitive (to an American) layout of the computer keyboard. And now? We're all sitting on the Galata Bridge, watching the sun set on the other side of the Golden Horn, bathed in a honey-colored light that my ratty digital camera failed to capture. The conical shape to the right of her head is the distant Galata Tower, right next door to our hotel. Due to a fluke we got the absurdly fancy suite on the top floor, outfitted with every conceivable amenity except for hot water. Hence the bracing, chilly sponge baths and my reluctance to shave. Aside from that it was perfect, and the views of the adjacent tower--built in 1348 by the Genoese, now housing a dreary nightclub with steamtable food--made me forget the hot-water problem for literally minutes at a time.As I was saying...

They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load,

And they seem not to break; though once they are bowed

So low for long, they never right themselves:

You may see their trunks arching in the woods

Years afterward, trailing their leaves on the ground

Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair

Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.

Tuesday, July 19, 2005

HOM returns: Istanbul, Pamuk, Ron Rosenbaum, SAR

As it happens, that's where Orhan Pamuk has spent much of his life, and where he wrote Istanbul: Memories and the City, which I began reading shortly after my floundering visit to his neighborhood. I haven't finished it yet. What strikes me so far is the pervasive sense of melancholy, which the Turks call hüzün. Pamuk is careful to differentiate this emotion from the solitary blackness described by, say, Robert Burton. Hüzün is a communal feeling--an equal-opportunity brand of desolation--shared by all Istanbullus, living as they do amid the wreckage of a great past. The double-decker ruins of the Byzantine and Ottoman empires, he writes, "are reminders that the present city is so poor and confused that it can never again dream of rising to its former heights of wealth, power, and culture. It is no more possible to take pride in these neglected dwellings, which dirt, dust, and mud have blended into their surroundings, than it is to rejoice in the beautiful old wooden houses that as a child I watched burn down one by one."

As it happens, that's where Orhan Pamuk has spent much of his life, and where he wrote Istanbul: Memories and the City, which I began reading shortly after my floundering visit to his neighborhood. I haven't finished it yet. What strikes me so far is the pervasive sense of melancholy, which the Turks call hüzün. Pamuk is careful to differentiate this emotion from the solitary blackness described by, say, Robert Burton. Hüzün is a communal feeling--an equal-opportunity brand of desolation--shared by all Istanbullus, living as they do amid the wreckage of a great past. The double-decker ruins of the Byzantine and Ottoman empires, he writes, "are reminders that the present city is so poor and confused that it can never again dream of rising to its former heights of wealth, power, and culture. It is no more possible to take pride in these neglected dwellings, which dirt, dust, and mud have blended into their surroundings, than it is to rejoice in the beautiful old wooden houses that as a child I watched burn down one by one."Nobody likes the post-imperial blahs, of course. The mighty, having fallen, are apt to be peevishly nostalgic. But after reading a couple of hundred pages, you begin to wonder whether Pamuk isn't seeing the city through hüzün-colored spectacles and projecting his personal sense of woe onto everything in sight. At one point during the trip I encountered an American woman who had lived in Istanbul during the late 1950s and early 1960s: the exact period Pamuk describes in the first half of his book. She had read not only parts of Istanbul but some of Pamuk's fictional output (she mentioned Snow), and found his morose portrait of the city almost unrecognizable. No doubt the author would reply that hüzün is an indigenous emotion, not something to be glommed onto by a Western visitor. Still, when Pamuk writes about Resat Ekram Kocu, author of the Istanbul Encyclopedia (which sounds like a vaguely homoerotic variation on Ripley's Believe It Or Not), he seems to acknowledge that sorrow might be a personal matter after all: "I'm left feeling that Kocu's sadness is less the result of the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the decline of Istanbul than of his own shadowy childhood in those yalis and kösks." Well, I'll keep reading.

Next: I share many of Ron Rosenbaum's enthusiasms. (Three cheers for Charles Portis!) I admire his smarts and polemical zeal. But he seems to have gone temporarily off the rails in his latest New York Observer piece, where he begins by disclosing a link between the opening of Nabokov's Pale Fire and a fairly obscure poem by Robert Frost. No problem there--especially since the brilliant Brian Boyd has signed off on this bit of textual sleuthing. It's all downhill from there, though. The long poem at the heart of Pale Fire, Rosenbaum argues,

is one of the most underrated American poems of the past century.... Some have mistakenly called it a parody; some have shown that it demonstrates the justness of [fictional poet John] Shade's self-deprecatory characterization of himself as an 'oozy footstep' behind Frost. In fact, taken on its own, it surpasses in every respect anything that Frost has ever done. Deal with it, Frostians.It takes an ear of the purest tin--a kind of metallurgical wonder--to make these assertions. Nabokov was a great novelist but a minor poet. The diction of "Pale Fire" dips into poetic flabbiness with the very second line ("false azure" indeed), and while there are passages of tremendous beauty and cutting wit, VN just isn't in the same ballpark as top-drawer Frost. No comparison. Deal with it, Nabokovians.

Finally, I've been listening to the lavish two-disc delight that is Sam Cooke's SAR Records Story 1959-1965. SAR was Cooke's own label, a hothouse-cum-laboratory where he reigned as producer, songwriter, and impresario. The first disc is gospel (which the canny Cooke kept nudging toward pop), the second disc is pop (which he tried to infuse with at least a hint of gospel ardor), and there's plenty of wheat amidst the chaff. Hell, even the chaff is pretty damn great. You get the Soul Stirrers--with Paul Foster, Jimmie Outler, and Johnnie Taylor all laboring mightily to fill the departed Cooke's shoes--and R.H. Harris and three excellent cuts by the youthful Womack Brothers. Note their stirring version of "Somewhere There's A God," with Curtis Womack pulling out all the stops. Then, on the pop side, note the quasi-identical "Somewhere There's A Girl," sung by Cooke himself--talk about turning on a secular dime! All this plus the Simms Twins, the Valentinos (as the Womack Brothers were quick to christen themselves when they went pop), and a throwaway instrumental by Billy Preston, who must have still been in short pants at the time.