Monday, August 22, 2005

Brief Encounter: David Carkeet

The author of five novels, David Carkeet has now broken the nonfiction barrier with a hilariously inventive memoir, Campus Sexpot. A comical hologram of small-town life in the early Sixties, the book recounts the author's sentimental (and erotic) education. There is, however, an additional magic ingredient. When Carkeet was fifteen, a former teacher at his high school published a smutty roman-a-clef, also called Campus Sexpot, which scandalized the entire populace. More than four decades later, a dogeared copy of Dale Koby's pulpy production does for Carkeet what that damn madeleine did for Proust: it opens the portals of memory. It also offers a kind of primer in How Not To Write, which makes Campus Sexpot one of the least conventional works of literary criticism I've read in a long time--not to mention the funniest.

The author of five novels, David Carkeet has now broken the nonfiction barrier with a hilariously inventive memoir, Campus Sexpot. A comical hologram of small-town life in the early Sixties, the book recounts the author's sentimental (and erotic) education. There is, however, an additional magic ingredient. When Carkeet was fifteen, a former teacher at his high school published a smutty roman-a-clef, also called Campus Sexpot, which scandalized the entire populace. More than four decades later, a dogeared copy of Dale Koby's pulpy production does for Carkeet what that damn madeleine did for Proust: it opens the portals of memory. It also offers a kind of primer in How Not To Write, which makes Campus Sexpot one of the least conventional works of literary criticism I've read in a long time--not to mention the funniest. James Marcus: Campus Sexpot is an unusual blend of memoir and literary (or sub-literary) criticism. But what came first--the desire to write about your boyhood, or the desire to write about Dale Koby's potboiler? And how did one lead to the other?

David Carkeet: I'd been a straight fiction writer for years, but when I hit middle age, my boyhood and the characters peopling it suddenly announced themselves as material to write about, arriving at my doorstep like a troupe of traveling actors ready to perform. I started writing short memoirs, and then I felt the urge to "go long"--to write a book-length memoir with a single focus. Around that time I tracked down a copy of the 1961 Campus Sexpot. I didn't know how I would use it, but its arrival in town when I was in high school was such a strong memory that it seemed right as a vehicle--a real jalopy--to take me into the past.

Marcus: You seem almost to be rooting for Koby's book to be better than it is. But if Koby had written a real novel rather than a soft-core potboiler, wouldn't that have ruined your own project?

Carkeet: I was the most disappointed man on earth when I reread Campus Sexpot. It was bad in such mundane, uninteresting ways that I didn't see how I could possibly use it, and I gave up the idea for a while. Then I read it again. (I've read it probably eight or ten times; in that respect it's up there with Huck Finn and Lucky Jim.) I started writing, and the idea of associating from Koby's idiotic story to my own past occurred to me as I wrote the first chapter--a chapter that came out very much as it appears in the finished book. When the big-breasted girl deliberately brushes up against the hero of Campus Sexpot, and when I remembered that the same thing happened to me and that a story was attached to the incident, off I went. That moment of connection dictated the form of the rest of the book. Now, of course, I'm delighted his book stunk. Bad writing is a funnier subject than good writing.

Marcus: Your book includes a funny and fascinating chapter on The International Order of DeMolay, a Masonic organization for kids. Despite the glittering list of alumni (Walt Disney! Richard Nixon! The Smothers Brothers!), I had never even heard of DeMolay before. Has anybody else written about it? Does it still exist? Would you be willing to share the secret handshake?

Carkeet: I think DeMolay was mainly a small-town phenomenon, and perhaps you're a big-city boy. My treatment draws from a fact-filled 1960 Ph.D. dissertation by an ex-DeMolay named John Rhoads, but apart from that and the official literature from the organization, I know of no discussions of it. It survives, but with declining membership. DeMolay is important in the way it distilled the whole process of acculturation: here's a body of belief, a creed consisting of threadbare platitudes, and you'd better subscribe to it or there's something wrong with you. I subscribed! And when I grew up, I looked back and said, "What was THAT?" But I'm still too good a boy to reveal the secret handshake to an infidel.

Marcus: "A small town is a defensively cocky place," you write, "quick to brag about its superiority before you can make fun of it." It seems to me you do both in Campus Sexpot, praising the basic decency of Sonora even as you (comically) recoil from its Peyton-Place-like claustrophobia. But which do you think predominates?

Carkeet: Sonora had the combined sweetness and stupidity of all small towns. It was a heaven of comfortableness for a boy growing up in the '50s and early '60s, but it was a cultural backwater. My cosmology was completely Sonora-centric, right up to college. If I'd drawn a map of the universe, everything would have revolved around the golden sun of Sonora. I can't speak to what the town is like now, but I think I gave a fair account of the Sonora of my youth. And I took pains to embarrass no one but myself.

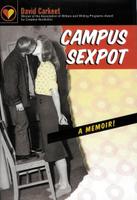

Marcus: Is that photo on the cover really you?

Carkeet: Yes, for the Christmas issue of the school newspaper, I, the shortest freshman, stood on a chair under the mistletoe and kissed the tallest senior. I felt both humiliated and incredibly lucky. I'm proud to report that when the kiss was reprinted in the yearbook at the end of the school year, the tall senior got ahold of my yearbook and wrote across the photo, "Remember this, Dave? Yummmm!"

Carkeet: Yes, for the Christmas issue of the school newspaper, I, the shortest freshman, stood on a chair under the mistletoe and kissed the tallest senior. I felt both humiliated and incredibly lucky. I'm proud to report that when the kiss was reprinted in the yearbook at the end of the school year, the tall senior got ahold of my yearbook and wrote across the photo, "Remember this, Dave? Yummmm!" Marcus: On a more technical note, how did you find the switch from fiction to nonfiction? Are you contemplating another nonfiction book, or will you happily return to making the whole thing up?

Carkeet: Both forms feel very natural to me, and if I had the energy, I would work in one of them in the morning and the other in the afternoon. In writing fiction, there is no greater pleasure than being in the midst of a dialogue scene where things are really popping--the characters are having strong feelings, the reader is learning new stuff, it's funny (got to be funny), and the scene sends the book off in a surprising new direction. Nonfiction affords different pleasures. Narrative is still possible, of course, and my memoirs contain far more stories than meditations. But I also love the memoir's emotional descent into the maelstrom, where the author is determined to pinpoint the feeling associated with a problematic event. As someone once said of nonfiction vs. fiction, in nonfiction, you get to tell, not just show. But the telling can be overdone, and if an emotion doesn't need to be named--if it's clear from the story itself--I try not to name it. Both forms should surprise the writer at work, even nonfiction. As you write anything, if you're not agitated and expectant and curious and wriggling in your chair, the outcome will be dull.

Marcus: As Dale Koby's example makes clear, writing about sex can be a perilous enterprise. Who do you think is actually good at it? (The writing, I mean, not the sex.)

Carkeet: When I'm reading fiction, an erotic scene always sends me off on a different path, destroying all the authorial work of illusion-making. Besides that, I tend to read sex scenes as how-to tips. (Perhaps we should try this. But how to suggest it after all these years?) Or, after the scene is over, I itch for more, which reminds me of a moment in a Martin Amis novel where a character who watches nothing but porn is surprised, as he watches a regular TV show, that the characters are not disrobing. I will never be able to write a sex scene except in an elliptic, comic style. In one of his novels, David Lodge describes a gentle academic so attentive to his partner's needs that he lingers over her as if studiously leafing through a file-card index. Perfect.

Marcus: "The trash we read as kids stays with us--the characters, the words," you point out. "The unresolved questions about technique and anatomy linger for decades." What were your truly formative books (aside from Dale Koby, of course)?

Carkeet: I was a stupid reader as a child, and accounts of precocious, voracious reading, like Annie Dillard's in An American Childhood, make me hang my head in shame. Then I dumbly majored in German--I really nailed Schiller's Maria Stuart if you ever want to discuss it. The big moment of useful reading came in graduate school. A good friend and fellow-linguist introduced me to Kingsley Amis' novels, and we read them over and over and savored them--the characters, the vocabulary, the meanness that springs from frustration. I felt that Amis' mode of expression was like mine, only better, and by rereading him, I became him stylistically. My first novel, a mystery titled Double Negative, is pretty much Lucky Jim with a corpse. Over time, as I wrote more, I slew the master and all that, but my early writing is a striking instance of the deliberate imitation of an artistic model.

Marcus: Did you know from the beginning that you would conclude with that chapter on your father? I ask because it's such a graceful, touching, and surprising way to wrap up what initially seems like a satirical undertaking.

Carkeet: When I started writing the book, I had no idea that my father would even make an appearance, but at about the mid-point I suspected he would conclude it, and I started taking notes for that chapter. By the time I reached the end, the profile of him was absolutely inevitable. The tone of it is certainly different from the tone of the beginning of the book, but there are suggestions of the tone earlier. Besides, a memoir can be dynamic just like a novel. My work in the novel made me comfortable about the shape of the whole thing.

Marcus: Finally, another phrase that struck me: "Unhappy men write unhappy books." What about Campus Sexpot? A happy or unhappy book?

Carkeet: This question sends me into a tizzy, because my first reaction is that my memoir is a sad book but I think I'm a happy man, which makes me want to dump my own aphorism. I associate sadness with Campus Sexpot because of its final chapter about my father, ending with his death, but this is a mistake because it really ends with his final words to me, a send-off into the world, and that's a happy outcome. It's the very end of a book that establishes its "happiness"--which is now suddenly striking me as a rather elementary critical concept. (Take Frank Conroy's Stop-Time, a harrowing boyhood memoir, but it ends with this moment: Conroy nervously arrives at college, and an upperclassman grabs his suitcase for him and says, "Welcome to Haverford." What a joyful ending, and it affects the whole feel of the book.) But beyond the ending of my book, there's something that I'll call The Happiness of the Attained Perspective, something implicit in almost all memoirs: I made it, I'm here, I'm healthy enough to write about this, and that's a reason to be happy.

Comments:

<< Home

David Carkeet is my father's 1st cousin (does that make me his 2nd cousin? 1st cousin once-removed? I can't recall). Oddly, I also dumbly majored in German. Nonetheless, I am proud of David for his success, and I am proud to be named after David's father, my great uncle.

Ross Carkeet

Ross Carkeet

David Carkeet was my writing instuctor at University of Missouri St.Louis. I couldn't have hoped for a better teacher and mentor. He's pretty good at that whole novelist thing too.

Chris Pratt

Chris Pratt

I was a year behind Dave at Sonora High School and was in DeMolay with him as well. His description of life in Sonora and DeMolay are equally accurate. It was truly a joy to read Campus Sexpot for the rekindling of memories.

The pulp fiction novel written by my father was intended as a snub at the small town of Sonora and some of its leading citizens - like Carkeet's father for example - the drunk judge who could always be found at the local bar. It was not supposed to be good. It was dashed out in less than an hour.

Just to set the record straight-it was not my father who was having the affair with the girl it was the boy's P.E. coach who was good friends with my father. My father covered for the coach's affair and that is what got him in trouble. My father expected the coach to come forward when the accusations were made against my father. It was a betrayal my father, then a young man fresh out of the service, never forgot. It should also be noted that the principal knew it wasn't my father but since my father wouldn't reveal the names of who was involved he was fired. I remember visiting the coach's home and playing with his children. I also remember the scandal, and my parents packing and leaving town in the middle of the night.

I remember my mother being furious with my father for not breaking the 'manly code of silence.' The only adult who didn't know the truth about the affair was the coach's wife.

My father went on to become an editor and a publisher, not of pornography but of car and van magazines until he returned to teaching high school. He was killed by a drunk driver on his way to Cal State Northridge on October 9, 1979.

Calling my father a pornographer is patently unfair as he took the job just to make money to feed his family in the wake of his being fired. He left that industry as soon as he could. He called the time he worked in that industry his greatest regret. Our family has and continues to seek out all illicit material with my father's name on it. The material is destroyed. It was his last request.

Just to set the record straight-it was not my father who was having the affair with the girl it was the boy's P.E. coach who was good friends with my father. My father covered for the coach's affair and that is what got him in trouble. My father expected the coach to come forward when the accusations were made against my father. It was a betrayal my father, then a young man fresh out of the service, never forgot. It should also be noted that the principal knew it wasn't my father but since my father wouldn't reveal the names of who was involved he was fired. I remember visiting the coach's home and playing with his children. I also remember the scandal, and my parents packing and leaving town in the middle of the night.

I remember my mother being furious with my father for not breaking the 'manly code of silence.' The only adult who didn't know the truth about the affair was the coach's wife.

My father went on to become an editor and a publisher, not of pornography but of car and van magazines until he returned to teaching high school. He was killed by a drunk driver on his way to Cal State Northridge on October 9, 1979.

Calling my father a pornographer is patently unfair as he took the job just to make money to feed his family in the wake of his being fired. He left that industry as soon as he could. He called the time he worked in that industry his greatest regret. Our family has and continues to seek out all illicit material with my father's name on it. The material is destroyed. It was his last request.

I was born in 1967 so I don’t know anything about this. I do remember driving around in the desert with my father in a different 4X4 every month for his job at an off-road magazine. He even let me drive one of them all the way from Lancaster to Rosamond on dirt roads. I know he wrote those smutty books because they exist but his interests were history. Especially gold country history. When we went out to test drive the 4X4s we usually ended up at an old mine or ghost town in the Southern California desert. I guess I just wanted to give you my memoir of my father as I saw him, a loving father, not as the failed writer he is being portrayed as.

For a writer there is no worse feeling than regret for what one has written. Looking back on the writing of this memoir, I can see that, caught up as I was in the exploration of my past and its links to Dale Koby’s writing, I presumed too much about the man. I also gave insufficient thought to the effect my incomplete sketch of him could have on his family. That sketch now strikes me as thoughtless and judgmental, and I regret the hurt it must have caused. --David Carkeet

Post a Comment

<< Home