Wednesday, August 31, 2005

HOM returns, Bill Frisell's latest

I'm back from Oregon. The hike from the trailhead to the humorously named Cliffs of Nannie was a brute, straight uphill for two miles over dusty switchbacks, without even a decent view. Luckily the trail leveled off after that, and we got a visual payoff--the slumping, snowcapped summit of Mount Adams--before dropping down to Sheep Lake. The lake itself was shallow, cool, stocked with some kind of mutated tadpoles and, the first afternoon, a party of skinny-dipping campers who had hiked in from Cispus Pass. Nature is a beautiful thing. Insects flew overhead making a sound like castanets. Some aggressive jays tried to steal our food. We also encountered a large gray marmot beneath the Cliffs of Nannie. This site calls them "charismatic sciurid rodents," and the guy did have a certain flair, standing his ground very nicely before sauntering up the hillside to a hidden burrow. Every night in the tent, with the headlamp strapped to my forehead, I tried to read a few pages of the new Kadare. Not much luck on that front. But I do have a backlog of books to discuss over the next few days--Leonard Michaels's Going Places, Robert Louis Stevenson's The Beach of Falesá, and Kayla Williams's I Love My Rifle More Than You--and I'll keep going with Ismail K.

I'm back from Oregon. The hike from the trailhead to the humorously named Cliffs of Nannie was a brute, straight uphill for two miles over dusty switchbacks, without even a decent view. Luckily the trail leveled off after that, and we got a visual payoff--the slumping, snowcapped summit of Mount Adams--before dropping down to Sheep Lake. The lake itself was shallow, cool, stocked with some kind of mutated tadpoles and, the first afternoon, a party of skinny-dipping campers who had hiked in from Cispus Pass. Nature is a beautiful thing. Insects flew overhead making a sound like castanets. Some aggressive jays tried to steal our food. We also encountered a large gray marmot beneath the Cliffs of Nannie. This site calls them "charismatic sciurid rodents," and the guy did have a certain flair, standing his ground very nicely before sauntering up the hillside to a hidden burrow. Every night in the tent, with the headlamp strapped to my forehead, I tried to read a few pages of the new Kadare. Not much luck on that front. But I do have a backlog of books to discuss over the next few days--Leonard Michaels's Going Places, Robert Louis Stevenson's The Beach of Falesá, and Kayla Williams's I Love My Rifle More Than You--and I'll keep going with Ismail K. Meanwhile, I reviewed the new live Bill Frisell, East/West, for WBUR Online Arts:

Meanwhile, I reviewed the new live Bill Frisell, East/West, for WBUR Online Arts:Will the real Bill Frisell please stand up? It's a question his admirers have been asking with increasing frequency over the past decade, as the brilliant guitarist and composer has donned and discarded all manner of stylistic finery: jazz, bluegrass, rock, world beat, and electronica. On a recent, unusually wide-ranging disc, Richter 858, he actually subbed for one of the violins in a string quartet. You have to hand it to the guy. Who else would be so self-effacing as to play second fiddle on his own recording?It might not be clear from this opening salvo, but I loved the two-disc set, with a couple of minor caveats. You can read the entire review here.

Thursday, August 25, 2005

Westward, ho

I'm off to Oregon until Wednesday morning, with a song on my lips and the new Ismail Kadare in my carry-on bag. Barring a lumbar flare-up, I'll be marching through the Cascades by Saturday morning, and therefore well out of wireless range. HOM will resume on Wednesday. In the meantime, congratulations to David Ulin and David Kipen--clearly it's a good day to be a Californian bibliophile named David with, you know, a touch of gray. Excellent choices both!

Wednesday, August 24, 2005

Philip Larkin

Last night I pulled out Larkin's Collected Poems--the nice green FSG edition with its tiny image of the bespectacled, non-photogenic poet--and trawled around for a few minutes. I had a heating pad under my lower back, since I had foolishly bent over to pick up my son's duffel bag last weekend and felt a novel, lasting jolt of pain in that general vicinity. I had also taken two muscle relaxant pills (no jokes, please) and was silently praying for them to take effect. My mood of middle-age decrepitude made Larkin seem like a good choice. Of course his reputation has taken a certain pounding over the past 15 years. As Martin Amis put it, in a 1995 speech I came across on the Web: "Larkin is now something like a pariah, or an untouchable. The word 'Larkinesque' used to evoke the wistful, the provincial, the crepuscular, the unloved. Now it evokes the scabrous and the supremacist. The word 'Larkinism' used to stand for a certain sort of staid, decent, wary Englishness. Now it refers to the articulate far right. In the early Eighties, the common mind imagined Larkin as a reclusive drudge...slumped in a shabby library, gaslight against the dusk. In the mid-Nineties, however, we see a fuddled Scrooge and bigot, his singlet-clad form barely visible through a mephitis of alcohol, anality and spank magazines." Amis goes on to point out that the three-ring circus of political correctness is meaningless, that only the poems count--and of course he's right. Here's the last, lovely stanza of "Money":

I listen to the money singing. It's like looking down

From long french windows at a provincial town,

The slums, the canal, the churches ornate and mad

In the evening sun. It is intensely sad.

Tuesday, August 23, 2005

Other Men's Daughters

The fine folks at Newsday asked me to contribute one of those short, Summer Reading/Bookends things, and since I was still on my Richard Stern jag, I did Other Men's Daughters. You'll find my two cents below. But if you follow the link to the Newsday website, you'll get a special extra: Nina's thing on the most depressing beach blanket book of all time, Isaac Babel's 1920 Diary. Pass the Coppertone! (P.S.: My byline appears below Nina's name. True, we live together, but this promiscuous mingling of bylines must stop immediately.)

Books about failed marriages are as old as the Bible (Adam and Eve, after all, had the shortest honeymoon on record). Yet most novelists play favorites with their feuding spouses. In Other Men's Daughters (Triquarterly Books/Northwestern, $15.95 paper), one of the truest and saddest portraits of a disintegrating marriage, Richard Stern does not. Granted, the focus remains on Robert Merriwether, a Harvard academic whose specialty--the physiology of thirst--does nothing to improve his desiccated home life. Our sympathies are mostly with him. From time to time, though, we get a glimpse of the household through the embittered eyes of his wife, Sarah, and discover that her grievances are no less raw or real. This balancing act is exquisitely calibrated. So is Merriwether's romance with a fetching undergraduate. Stern resists the easy, satiric angle--the stuff of a million "Blue Angel" knockoffs--and concentrates instead on the painful realities of this American-style vita nuova.P.P.S.: The very same issue of Newsday also includes this excellent review of Tim Farrington's Lizzie's War by the inimitable Kerry Fried. Don't overlook the opening broadside: "Rumor has it we're in a 'nonfiction moment.' And sadly, when it comes to quality, books on the nonfiction bestseller lists do trump many novels in the opposite column. Satisfying, inventive fiction is hardly in short supply, but it has become increasingly difficult for even established novelists (this year, Meg Wolitzer, Jonathan Coe, Rupert Thomson, Hilary Mantel and Kazuo Ishiguro have merited far more readers) to slip into something more profitable."

And what about the style? The protagonist eats, sleeps and breathes physiology. Stern, always on the lookout for linguistic nutrients, swallows its vocabulary whole. The effect is wonderfully enriching. At one point, the infatuated Merriwether wonders at the mechanism of feeling itself. Is it deep or superficial? Well, one centimeter of human skin contains "four yards of nerves, twenty-five pressure apparatuses for tactile stimuli, two hundred nerve cells to record pain. This fantastic factory is our surface. No wonder our feeling is so exposed. Our hearts are on our sleeve." It's like encountering John Donne in a white lab coat.

Monday, August 22, 2005

Brief Encounter: David Carkeet

The author of five novels, David Carkeet has now broken the nonfiction barrier with a hilariously inventive memoir, Campus Sexpot. A comical hologram of small-town life in the early Sixties, the book recounts the author's sentimental (and erotic) education. There is, however, an additional magic ingredient. When Carkeet was fifteen, a former teacher at his high school published a smutty roman-a-clef, also called Campus Sexpot, which scandalized the entire populace. More than four decades later, a dogeared copy of Dale Koby's pulpy production does for Carkeet what that damn madeleine did for Proust: it opens the portals of memory. It also offers a kind of primer in How Not To Write, which makes Campus Sexpot one of the least conventional works of literary criticism I've read in a long time--not to mention the funniest.

The author of five novels, David Carkeet has now broken the nonfiction barrier with a hilariously inventive memoir, Campus Sexpot. A comical hologram of small-town life in the early Sixties, the book recounts the author's sentimental (and erotic) education. There is, however, an additional magic ingredient. When Carkeet was fifteen, a former teacher at his high school published a smutty roman-a-clef, also called Campus Sexpot, which scandalized the entire populace. More than four decades later, a dogeared copy of Dale Koby's pulpy production does for Carkeet what that damn madeleine did for Proust: it opens the portals of memory. It also offers a kind of primer in How Not To Write, which makes Campus Sexpot one of the least conventional works of literary criticism I've read in a long time--not to mention the funniest. James Marcus: Campus Sexpot is an unusual blend of memoir and literary (or sub-literary) criticism. But what came first--the desire to write about your boyhood, or the desire to write about Dale Koby's potboiler? And how did one lead to the other?

David Carkeet: I'd been a straight fiction writer for years, but when I hit middle age, my boyhood and the characters peopling it suddenly announced themselves as material to write about, arriving at my doorstep like a troupe of traveling actors ready to perform. I started writing short memoirs, and then I felt the urge to "go long"--to write a book-length memoir with a single focus. Around that time I tracked down a copy of the 1961 Campus Sexpot. I didn't know how I would use it, but its arrival in town when I was in high school was such a strong memory that it seemed right as a vehicle--a real jalopy--to take me into the past.

Marcus: You seem almost to be rooting for Koby's book to be better than it is. But if Koby had written a real novel rather than a soft-core potboiler, wouldn't that have ruined your own project?

Carkeet: I was the most disappointed man on earth when I reread Campus Sexpot. It was bad in such mundane, uninteresting ways that I didn't see how I could possibly use it, and I gave up the idea for a while. Then I read it again. (I've read it probably eight or ten times; in that respect it's up there with Huck Finn and Lucky Jim.) I started writing, and the idea of associating from Koby's idiotic story to my own past occurred to me as I wrote the first chapter--a chapter that came out very much as it appears in the finished book. When the big-breasted girl deliberately brushes up against the hero of Campus Sexpot, and when I remembered that the same thing happened to me and that a story was attached to the incident, off I went. That moment of connection dictated the form of the rest of the book. Now, of course, I'm delighted his book stunk. Bad writing is a funnier subject than good writing.

Marcus: Your book includes a funny and fascinating chapter on The International Order of DeMolay, a Masonic organization for kids. Despite the glittering list of alumni (Walt Disney! Richard Nixon! The Smothers Brothers!), I had never even heard of DeMolay before. Has anybody else written about it? Does it still exist? Would you be willing to share the secret handshake?

Carkeet: I think DeMolay was mainly a small-town phenomenon, and perhaps you're a big-city boy. My treatment draws from a fact-filled 1960 Ph.D. dissertation by an ex-DeMolay named John Rhoads, but apart from that and the official literature from the organization, I know of no discussions of it. It survives, but with declining membership. DeMolay is important in the way it distilled the whole process of acculturation: here's a body of belief, a creed consisting of threadbare platitudes, and you'd better subscribe to it or there's something wrong with you. I subscribed! And when I grew up, I looked back and said, "What was THAT?" But I'm still too good a boy to reveal the secret handshake to an infidel.

Marcus: "A small town is a defensively cocky place," you write, "quick to brag about its superiority before you can make fun of it." It seems to me you do both in Campus Sexpot, praising the basic decency of Sonora even as you (comically) recoil from its Peyton-Place-like claustrophobia. But which do you think predominates?

Carkeet: Sonora had the combined sweetness and stupidity of all small towns. It was a heaven of comfortableness for a boy growing up in the '50s and early '60s, but it was a cultural backwater. My cosmology was completely Sonora-centric, right up to college. If I'd drawn a map of the universe, everything would have revolved around the golden sun of Sonora. I can't speak to what the town is like now, but I think I gave a fair account of the Sonora of my youth. And I took pains to embarrass no one but myself.

Marcus: Is that photo on the cover really you?

Carkeet: Yes, for the Christmas issue of the school newspaper, I, the shortest freshman, stood on a chair under the mistletoe and kissed the tallest senior. I felt both humiliated and incredibly lucky. I'm proud to report that when the kiss was reprinted in the yearbook at the end of the school year, the tall senior got ahold of my yearbook and wrote across the photo, "Remember this, Dave? Yummmm!"

Carkeet: Yes, for the Christmas issue of the school newspaper, I, the shortest freshman, stood on a chair under the mistletoe and kissed the tallest senior. I felt both humiliated and incredibly lucky. I'm proud to report that when the kiss was reprinted in the yearbook at the end of the school year, the tall senior got ahold of my yearbook and wrote across the photo, "Remember this, Dave? Yummmm!" Marcus: On a more technical note, how did you find the switch from fiction to nonfiction? Are you contemplating another nonfiction book, or will you happily return to making the whole thing up?

Carkeet: Both forms feel very natural to me, and if I had the energy, I would work in one of them in the morning and the other in the afternoon. In writing fiction, there is no greater pleasure than being in the midst of a dialogue scene where things are really popping--the characters are having strong feelings, the reader is learning new stuff, it's funny (got to be funny), and the scene sends the book off in a surprising new direction. Nonfiction affords different pleasures. Narrative is still possible, of course, and my memoirs contain far more stories than meditations. But I also love the memoir's emotional descent into the maelstrom, where the author is determined to pinpoint the feeling associated with a problematic event. As someone once said of nonfiction vs. fiction, in nonfiction, you get to tell, not just show. But the telling can be overdone, and if an emotion doesn't need to be named--if it's clear from the story itself--I try not to name it. Both forms should surprise the writer at work, even nonfiction. As you write anything, if you're not agitated and expectant and curious and wriggling in your chair, the outcome will be dull.

Marcus: As Dale Koby's example makes clear, writing about sex can be a perilous enterprise. Who do you think is actually good at it? (The writing, I mean, not the sex.)

Carkeet: When I'm reading fiction, an erotic scene always sends me off on a different path, destroying all the authorial work of illusion-making. Besides that, I tend to read sex scenes as how-to tips. (Perhaps we should try this. But how to suggest it after all these years?) Or, after the scene is over, I itch for more, which reminds me of a moment in a Martin Amis novel where a character who watches nothing but porn is surprised, as he watches a regular TV show, that the characters are not disrobing. I will never be able to write a sex scene except in an elliptic, comic style. In one of his novels, David Lodge describes a gentle academic so attentive to his partner's needs that he lingers over her as if studiously leafing through a file-card index. Perfect.

Marcus: "The trash we read as kids stays with us--the characters, the words," you point out. "The unresolved questions about technique and anatomy linger for decades." What were your truly formative books (aside from Dale Koby, of course)?

Carkeet: I was a stupid reader as a child, and accounts of precocious, voracious reading, like Annie Dillard's in An American Childhood, make me hang my head in shame. Then I dumbly majored in German--I really nailed Schiller's Maria Stuart if you ever want to discuss it. The big moment of useful reading came in graduate school. A good friend and fellow-linguist introduced me to Kingsley Amis' novels, and we read them over and over and savored them--the characters, the vocabulary, the meanness that springs from frustration. I felt that Amis' mode of expression was like mine, only better, and by rereading him, I became him stylistically. My first novel, a mystery titled Double Negative, is pretty much Lucky Jim with a corpse. Over time, as I wrote more, I slew the master and all that, but my early writing is a striking instance of the deliberate imitation of an artistic model.

Marcus: Did you know from the beginning that you would conclude with that chapter on your father? I ask because it's such a graceful, touching, and surprising way to wrap up what initially seems like a satirical undertaking.

Carkeet: When I started writing the book, I had no idea that my father would even make an appearance, but at about the mid-point I suspected he would conclude it, and I started taking notes for that chapter. By the time I reached the end, the profile of him was absolutely inevitable. The tone of it is certainly different from the tone of the beginning of the book, but there are suggestions of the tone earlier. Besides, a memoir can be dynamic just like a novel. My work in the novel made me comfortable about the shape of the whole thing.

Marcus: Finally, another phrase that struck me: "Unhappy men write unhappy books." What about Campus Sexpot? A happy or unhappy book?

Carkeet: This question sends me into a tizzy, because my first reaction is that my memoir is a sad book but I think I'm a happy man, which makes me want to dump my own aphorism. I associate sadness with Campus Sexpot because of its final chapter about my father, ending with his death, but this is a mistake because it really ends with his final words to me, a send-off into the world, and that's a happy outcome. It's the very end of a book that establishes its "happiness"--which is now suddenly striking me as a rather elementary critical concept. (Take Frank Conroy's Stop-Time, a harrowing boyhood memoir, but it ends with this moment: Conroy nervously arrives at college, and an upperclassman grabs his suitcase for him and says, "Welcome to Haverford." What a joyful ending, and it affects the whole feel of the book.) But beyond the ending of my book, there's something that I'll call The Happiness of the Attained Perspective, something implicit in almost all memoirs: I made it, I'm here, I'm healthy enough to write about this, and that's a reason to be happy.

Wednesday, August 17, 2005

Department of corrections

On August 8, I quoted a famous claim by the late Al Aronowitz that he had introduced the Beatles to the joys of cannibis. Now Tim Appelo--pop-cultural Sainte-Beuve, author of the mega-selling Ally McBeal: The Official Guide, and (not incidentally) my former roommate at Amazon--begs to differ. He writes:

But you're wrong, said the pedant, re: Aronowitz introducing the Beatles to pot. That's what he told me in 1981, and everyone all his life, but in fact, the recent Magical Mystery Tours reveals that John got turned on in London by PJ Proby, the Texan rock giant whose real name was... JAMES MARCUS! (well, James Marcus Smith). John inhaled two enormous tokes, much to Cyn's horror, raced to upchuck in the bathtub, and went home in aromatic ignominy. So that's why when Dylan proffered Al's pot, John had Ringo try it first. Ringo smoked the whole thing alone, reported it OK, and only then did poltroonish Paul and John join in. (Later, when John insisted all 4 Fabs had to get trepanned immediately, Paul scotched it by saying, "OK--you first.") Paul wrote "Got to Get You Into My Life" to celebrate his new daily friend, and that's also the night he made Mal find paper so he could write the meaning of the universe, which the next morn turned out to be "There are seven levels!"I stand corrected.

Monday, August 15, 2005

To borrow and to borrow and to borrow...

The Judith Kelly plagiarism case grows curioser and curioser. It seemed bad (and odd) enough that a first-time memoirist recounting her wretched Catholic childhood would filch sentences from Hilary Mantel's comic novel Fludd. But Miller, a 61-year-old woman with an all-too-photographic memory, didn't stop there. Upon further examination, borrowed bits from Graham Greene and Charlotte Brönte began bobbing to the surface. The author has declared herself mortified; her publisher, Bloomsbury, has now scuttled plans to bring the book out in paperback. But the whole mess led me to ponder the perverse psychology of plagiarism. The most brazen offenders seem almost eager to be busted. They don't muddy the trail, transpose sentences, fiddle with key adjectives. They dare you to recognize their pilfered goods. And that brings me to Thomas Mallon, from whom I've semi-pilfered the musings above. He published an excellent study of plagiarism, Stolen Words, in 1989. Here's the review I wrote for Newsday:

In his earlier work, A Book of One's Own, Thomas Mallon examined that most private and least preening of literary creations, the diary. Granted, part of Mallon's purpose was to show just how practiced these cries from the heart may be. But even when we read a self-conscious diarist--the type for whom the labor of constructing a persona is never finished, but only abandoned--we can at least assume that the writer's words are his own.

For the subjects of Mallon's new book, however, this assumption no longer holds. As its title suggests, Stolen Words focuses on the history and practice of plagiarism. Ranging through several centuries of larceny, Mallon blows the whistle on such eminent shoplifters as Lawrence Sterne, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He collars more recent offenders from the worlds of academia and television. Halfway through the book, the reader may begin to wonder if a single writer in the history of literature has managed to avoid an occasional visit to the authorial chop shop.

Still, Mallon has more in mind than a rogues gallery. The primary concerns of his book, he tells us, are "plagiarism's psychology and its haphazard exposure and punishment." The psychology, in particular, exerts a queasy fascination, because as Mallon makes clear, the most celebrated filchers seem to operate out of compulsiveness. It's not as though Coleridge--who looted wholesale chunks of Schelling and Schlegel for his Biographia Literaria--couldn't cut it on his own. Nor did he hesitate to loudly accuse other writers of the very crime he’d just committed. Indeed, Coleridge is the very exemplar of what Mallon calls "the psychological profile of the plagiarist." He exhibits "the genuine talent that makes the need to steal seem, at least to his own readers, unthinkable; the loud abhorrence of others' trangressions and the spirited denial of his own; textual incrimination so obvious that one can only wonder if getting caught wasn’t part of what he had in mind for himself."

This perverse self-destructiveness, this will be to be caught, seems to unite plagiarists across the centuries: Mallon points out its presence in a much more recent theft. In 1979, at age 23, Jacob Epstein published a first novel called Wild Oats, which garnered considerable praise on both sides of the Atlantic. As it happened, though, this debut owed at least some portion of its success to somebody else's--namely, that of Martin Amis, who noticed several dozen sentences from one of his own published novels spliced neatly into Epstein's. As Mallon notes, the resultant flap doubtless provided a measure of spiteful comfort to other, aging young writers itching to get into print. But the brazen quality of Epstein's theft also prompts a flurry of discreet speculation from the author: "If your parents are important editors in New York [as Epstein’s were], what, after all, is the worst possible thing you can be caught doing? Your plagiarism can accomplish a sort of Oedipal slaying before, in keeping with tragic models, it becomes the instrument of self-slaughter."

In other chapters, Mallon considers the case of the former Texas Tech professor Jayme Sokolow, whose compulsive plagiarism went undetected--and then unpunished--for years, Senator Joseph Biden's oratorical borrowings, and a $101-million lawsuit over the provenance of the television show Falcon Crest. What this assemblage points to most clearly is our ultimate confusion about the crime: Mallon calls our thinking on the subject "primitive," and insists that "our fear of dealing fully with plagiarism when it’s just been exposed...leads us into bungling and injustice."

Despite its unifying themes, Stolen Words remains something of a miscellany. It rambles. It doesn’t funnel itself down to a polemical point. On the contrary, Mallon riddles his prose with footnotes and parenthetical asides, and generally meets the challenge of keeping the whole shebang aloft by sheer exercise of style. Here and there, he bends over backwards for a weak pun, or tries the reader’s patience with one too many narrative zigzags. But altogether, it's hard to imagine a more elegant or entertaining guide to the world of literary grand theft.

Friday, August 12, 2005

Bowling for dinari

Pardon this deviation from my normal, bookish beat, but I can't help myself: current events are driving me nuts. Here we go. According to a new report issued by the Iraqi Board of Supreme Audit, at least $500 million has been embezzled from the national defense budget by fraudulent middlemen. Minor palm-greasing is one thing. But this is a massive, systematic plundering of the till, and the more you read, the more you want to pull your hair out. One incredible example: the Board examined 89 contracts that had been signed between June 28, 2004 (when the U.S. handed over sovereignty) and Feb. 28, 2005. And as Knight-Ridder's Hannah Allam reports, "the sole beneficiary on 43 of the 89 contracts was a former currency-exchange operator, Nair Mohamed al-Jumaili, whose name doesn't even appear on the contracts. At least $759 million in Iraqi money was deposited into his personal account at a bank in Baghdad, according to the report."

Pardon this deviation from my normal, bookish beat, but I can't help myself: current events are driving me nuts. Here we go. According to a new report issued by the Iraqi Board of Supreme Audit, at least $500 million has been embezzled from the national defense budget by fraudulent middlemen. Minor palm-greasing is one thing. But this is a massive, systematic plundering of the till, and the more you read, the more you want to pull your hair out. One incredible example: the Board examined 89 contracts that had been signed between June 28, 2004 (when the U.S. handed over sovereignty) and Feb. 28, 2005. And as Knight-Ridder's Hannah Allam reports, "the sole beneficiary on 43 of the 89 contracts was a former currency-exchange operator, Nair Mohamed al-Jumaili, whose name doesn't even appear on the contracts. At least $759 million in Iraqi money was deposited into his personal account at a bank in Baghdad, according to the report."Hold on. This guy had $759 million worth of NIDs (New Iraqi Dinaris) deposited into his personal bank account? Presumably he passed along at least some of this stash to arms suppliers in the United States, Poland, Pakistan, and the Arab world, but we'll never know how much. Nor did he get the best value for his money, since the Iraqis soon took possession of "shoddily refurbished helicopters from Poland, crates of loose ammunition from Pakistan and a fleet of leak-prone armored personnel carriers."

One more thought, though. The contracts under investigation add up to a whopping $1.27 billion. The money, we're told, did not come from the U.S. military budget or other foreign donations--it was siphoned directly from the Iraqi government. I found myself wondering how big a bite this would take out of the nation's resources. As it happens, it's pretty easy to figure out Iraq's projected revenues and expenditures for 2004: just stop by the Coalition Provisional Authority website and download the appropriate PDF. I'm no economist--I can hardly balance my checkbook--but I do see that the total projected revenues for 2004 add up to 19,258.8 billion NIDs, which equals about $12.839 billion. So the crooked contracts amount to ten percent of the entire budget for the year! Astounding, galling, demoralizing news. But I assume that Nair Mohamed al-Jumaili and his pals just took the old saying to heart: "Steal big and the world will love you."

Thursday, August 11, 2005

What about Bob?

As far as I'm concerned, Robert Novak wore out his welcome a long time ago. I admit to a certain masochistic delight in seeing him on television: it's like watching a Punch-and-Judy show with the most arrogant puppet on earth. But I wasn't suprised in the least when he started cussing and stalked off the set of Crossfire. To the Wall Street Journal this was a courageous act, an elbow in the solar plexus of Democratic hypocrisy. To just about everybody else, it was craven and pathetic. That's what makes Art Buchwald's column in the Washington Post so refreshing. He can't quite bring himself to kick his former colleague down the stairs. So he lurches back and forth between mild reproof and mild disdain, all the while showering Novak with the sort of quips that used to put a sparkle in Bob Hope's eye:

As far as I'm concerned, Robert Novak wore out his welcome a long time ago. I admit to a certain masochistic delight in seeing him on television: it's like watching a Punch-and-Judy show with the most arrogant puppet on earth. But I wasn't suprised in the least when he started cussing and stalked off the set of Crossfire. To the Wall Street Journal this was a courageous act, an elbow in the solar plexus of Democratic hypocrisy. To just about everybody else, it was craven and pathetic. That's what makes Art Buchwald's column in the Washington Post so refreshing. He can't quite bring himself to kick his former colleague down the stairs. So he lurches back and forth between mild reproof and mild disdain, all the while showering Novak with the sort of quips that used to put a sparkle in Bob Hope's eye:What made Novak such a successful reporter was that he had more sources than any columnist in Washington. If you wanted to do in an opponent, you leaked to Bob. He received so many leaks he had to have a sump pump in his office.Rim shot! No, but seriously folks, I hope his bratty behavior on CNN finally puts the Sultan of Smug out to pasture.

Wednesday, August 10, 2005

Orhan and Harry

In Sunday's Los Angeles Times Book Review, Michael Frank takes a look at Orhan Pamuk's Istanbul--and for the most part, he likes what he sees. Frank does issue a couple of caveats, including a swipe at the book's shaggy-dog construction: "Pamuk, the quintessential insider, sometimes becomes lost in a loop of personal reflection and digressive associations." Still, he admires the way that the author mingles municipal history with his own sentimental education. And as did I, Frank sees hüzün, Istbanbul's brand of self-flagellating melancholy, as the linchpin of the entire narrative:

The book's prevailing theme is Istanbul's unmistakable melancholy, or hüzün, which the writer characterizes as a "cultural concept conveying worldly failure, listlessness, and spiritual suffering" of a sort that comes about only when "the remains of a glorious past civilization are everywhere visible." Hüzün is a paradoxical, pervasive, deep-rooted and widely shared state of mind, and it coaxes from Pamuk the book's most glowing passage, a single-paragraph riff of nearly six pages that is a poem to cobblestones and pimps, soot and mossy barges, old ferries and '50s Chevrolets that serve as taxis, "everything being broken, worn out, past its prime." In short, Istanbul itself.Meanwhile, as widely reported, the Harry Potter series turns out to be the most popular reading material at Guantanamo Bay. According to the librarian, a civilian contractor, "We have Harry Potter in four languages, English, French, Farsi and Russian. We have it on order in Arabic. We do not have books 5 and 6 in the series, at this time. We have had several detainees read the series." At first I found this a little puzzling. Wouldn't J.K. Rowling's wizardly epic strike the detainees as piffle for infidels? But perhaps He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named has more than a passing resemblance to the Great Satan. Runner-up for the Gitmo Prize: Agatha Christie.

Tuesday, August 09, 2005

Edmund Wilson's crib

Yesterday I got a copy of Lewis M. Dabney's Edmund Wilson: A Life in Literature in the mail. Wilson is somebody I've tended to underestimate. I forced myself to read To the Finland Station as a college freshman, and it went right over my head, possibly because of my roots in the Marxist enclave of Scarsdale, New York. My next impression of him was formed by The Nabokov-Wilson Letters, where he operated at a distinct disadvantage: compared to VN's Fabergé friskiness, who wouldn't sound a little plodding? He seemed naive, too, in his dogged insistence that Lenin was a big-hearted humanist, rather than one more butcher in a pince-nez. But Dabney's formidable bio looks like the perfect antidote to my ignorance.

Flipping through it this morning, I came across a chapter about the death of Wilson's second wife, Margaret Canby. (He was to marry two more times.) After a rocky time together--par for the course, it seems--Maragaret went out to California to cool off, and there she died after falling down a flight of stairs. Wilson, tortured by guilt and loneliness, moved his possessions into a new house at 314 East 53rd Street. "This musty-smelling place," writes Dabney, "with 'lumpy and rubbed yellow walls,' amid the noise and grime of the slums--ironically, it would survive among the distinguished private homes on this street--was, until mid-decade, his base of operations."

Flipping through it this morning, I came across a chapter about the death of Wilson's second wife, Margaret Canby. (He was to marry two more times.) After a rocky time together--par for the course, it seems--Maragaret went out to California to cool off, and there she died after falling down a flight of stairs. Wilson, tortured by guilt and loneliness, moved his possessions into a new house at 314 East 53rd Street. "This musty-smelling place," writes Dabney, "with 'lumpy and rubbed yellow walls,' amid the noise and grime of the slums--ironically, it would survive among the distinguished private homes on this street--was, until mid-decade, his base of operations."

Hmm. I was pretty sure I knew exactly which building Dabney was talking about, since it's just around the corner from my apartment. On the way back from the gym (pale, crumpled, looking like a candidate for the Emergency Room) I detoured around the block. Sure enough, there it was, with a reasonably fresh coat of yellow paint on it. According to a plaque on the adjacent house, both were built in 1866. Directly across the street is Serena's Psychic Gallery and the Maracas Mexican Bar and Grill. Next door, an enormous crane and the nether parts of what will become an enormous residential skycraper, sure to blot out what's left of the yellow house's light. The mere presence of a wooden house in Manhattan is a touching thing. You can't quite believe that anything so pliable, so subject to mould and termites and fibrous decay, could possibly survive here. The fact that Wilson suffered such miseries within makes it even more touching. The noise and grime are still here. The slums are gone.

Flipping through it this morning, I came across a chapter about the death of Wilson's second wife, Margaret Canby. (He was to marry two more times.) After a rocky time together--par for the course, it seems--Maragaret went out to California to cool off, and there she died after falling down a flight of stairs. Wilson, tortured by guilt and loneliness, moved his possessions into a new house at 314 East 53rd Street. "This musty-smelling place," writes Dabney, "with 'lumpy and rubbed yellow walls,' amid the noise and grime of the slums--ironically, it would survive among the distinguished private homes on this street--was, until mid-decade, his base of operations."

Flipping through it this morning, I came across a chapter about the death of Wilson's second wife, Margaret Canby. (He was to marry two more times.) After a rocky time together--par for the course, it seems--Maragaret went out to California to cool off, and there she died after falling down a flight of stairs. Wilson, tortured by guilt and loneliness, moved his possessions into a new house at 314 East 53rd Street. "This musty-smelling place," writes Dabney, "with 'lumpy and rubbed yellow walls,' amid the noise and grime of the slums--ironically, it would survive among the distinguished private homes on this street--was, until mid-decade, his base of operations."Hmm. I was pretty sure I knew exactly which building Dabney was talking about, since it's just around the corner from my apartment. On the way back from the gym (pale, crumpled, looking like a candidate for the Emergency Room) I detoured around the block. Sure enough, there it was, with a reasonably fresh coat of yellow paint on it. According to a plaque on the adjacent house, both were built in 1866. Directly across the street is Serena's Psychic Gallery and the Maracas Mexican Bar and Grill. Next door, an enormous crane and the nether parts of what will become an enormous residential skycraper, sure to blot out what's left of the yellow house's light. The mere presence of a wooden house in Manhattan is a touching thing. You can't quite believe that anything so pliable, so subject to mould and termites and fibrous decay, could possibly survive here. The fact that Wilson suffered such miseries within makes it even more touching. The noise and grime are still here. The slums are gone.

Monday, August 08, 2005

Sony phony, high times, David Brooks, our friend Tiberius

Last week I was concentrating on the big fish (Richard Stern) and therefore overlooked a number of ephemeral, minnow-sized items. You'll have to forgive me. One such delight: Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Carolyn Kuhl gave Sony Pictures Entertainment a brisk slap on the wrist for inventing a bogus movie reviewer. The imaginary David Manning of The Ridgefield Press had plenty of nice things to say about such Sony releases as Vertical Limit, A Knight's Tale, The Animal, Hollow Man and The Patriot. What did the chimerical Mr. Manning think of Heath Ledger? He called him "this year's hottest new star!" Fascinating: even when the marketing department was actually putting words in the critic's mouth, they couldn't come up with any original ones. Along with paying a picayune $1.5 million fine, the studio has suspended two executives (i.e., sent them off for a quiet weekend of contrition at Two Bunch Palms) and pledged to "monitor its publicity and advertising more closely."

Next: Al Aronowitz, the so-called "godfather of rock journalism," passed away on August 1. According to David Segal's appreciation in the Washington Post, Aronowitz died a lonely and embittered man, which is sad to hear. At his peak, however, he partied with the best of them. He also engineered one of the great twofers in music history, introducing the Beatles to Bob Dylan and marijuana on the same day. The Fab Four, barricaded in their suite at the Delmonico Hotel, were initially a little dubious about the joint Dylan offered them. True, they had been gobbling amphetamines since their teenage gigs in Hamburg, but they weren't drug addicts, were they? A few puffs were enough to reassure them. The rest, in Aronowitz's recollection, is history:

Oy vey. To buttress this rickety assertion, Brooks cites a clutch of statistics: declining rates of domestic violence, drunk driving fatalities, teen pregnancies, divorce, and other such "indicators of social breakdown." (Did you know, by the way, that having sex with more than one person is an indicator of social breakdown? That's what did the Romans in.) Now, let's take one example. I'm as happy as Brooks is to hear that domestic battery is on the wane. But I don't believe that it's happening because, as he argues, "America is becoming more virtuous." So what's going on? According to a widely-cited study by two economists, Amy Farmer and Jill Thiefenthaler, the primary factor in the decline of domestic violence has been increased access to legal services for battered women. The study mentions nothing about kinder, gentler husbands. Brooks, I should add, is careful to note this very phenomenon, along with the passage of the Violence Against Women Act in 1994. Still, he ultimately ascribes the good news to an intangible uptick in our moral quality: "Americans today hurt each other less than they did 13 years ago." Right. That must account for the heartwarming jump in gun production since 2001. Apparently we need more rifles to not hurt each other with. As for that national epidemic of decency--it hasn't yet caught up with these people.

Finally, I was flipping through one of my all-time favorites the other day, Suetonius's The Twelve Caesars. Here's a choice paragraph or two on Tiberius, who looks pretty mediocre compared to his predecessor (Augustus) but an absolute prize compared to what came next (Caligula). He was, you will see, very eager to halt the decline in public morality:

Next: Al Aronowitz, the so-called "godfather of rock journalism," passed away on August 1. According to David Segal's appreciation in the Washington Post, Aronowitz died a lonely and embittered man, which is sad to hear. At his peak, however, he partied with the best of them. He also engineered one of the great twofers in music history, introducing the Beatles to Bob Dylan and marijuana on the same day. The Fab Four, barricaded in their suite at the Delmonico Hotel, were initially a little dubious about the joint Dylan offered them. True, they had been gobbling amphetamines since their teenage gigs in Hamburg, but they weren't drug addicts, were they? A few puffs were enough to reassure them. The rest, in Aronowitz's recollection, is history:

In no time at all, [Ringo] was laughing hysterically. His laughing looked so funny that the rest of us started laughing hysterically at the way Ringo was laughing hysterically. Soon, Ringo pointed at the way Brian Epstein was laughing, and we all started laughing hysterically at the way Brian was laughing.Luckily we've come a long way since the drug-addled Age of Aquarius. Or so David Brooks would have us believe, in his latest, dopiest op-ed column for the New York Times. Brooks used to be a smart, droll, articulate guy, and you still see flashes of his old elan when he's on television, trading barbs with a decent interlocutor. In print, he's turned into a neo-con Pollyanna. This week's news flash: America is in the midst of a Great Reawakening. "The good news is out there," he writes. "You want to know what a society looks like when it is in the middle of moral self-repair? Look around."

Oy vey. To buttress this rickety assertion, Brooks cites a clutch of statistics: declining rates of domestic violence, drunk driving fatalities, teen pregnancies, divorce, and other such "indicators of social breakdown." (Did you know, by the way, that having sex with more than one person is an indicator of social breakdown? That's what did the Romans in.) Now, let's take one example. I'm as happy as Brooks is to hear that domestic battery is on the wane. But I don't believe that it's happening because, as he argues, "America is becoming more virtuous." So what's going on? According to a widely-cited study by two economists, Amy Farmer and Jill Thiefenthaler, the primary factor in the decline of domestic violence has been increased access to legal services for battered women. The study mentions nothing about kinder, gentler husbands. Brooks, I should add, is careful to note this very phenomenon, along with the passage of the Violence Against Women Act in 1994. Still, he ultimately ascribes the good news to an intangible uptick in our moral quality: "Americans today hurt each other less than they did 13 years ago." Right. That must account for the heartwarming jump in gun production since 2001. Apparently we need more rifles to not hurt each other with. As for that national epidemic of decency--it hasn't yet caught up with these people.

Finally, I was flipping through one of my all-time favorites the other day, Suetonius's The Twelve Caesars. Here's a choice paragraph or two on Tiberius, who looks pretty mediocre compared to his predecessor (Augustus) but an absolute prize compared to what came next (Caligula). He was, you will see, very eager to halt the decline in public morality:

Tiberius cut down the expenses of public entertainments by lowering the pay of actors and setting a limit to the number of gladiatorial combats on any given festival. Once he protested violently against an absurd rise in the cost of Corinthian bronze statues, and of high quality fish--three mullets had been offered for sale at 100 gold pieces each! His proposal was that a ceiling should be imposed on the prices of household furniture, and that market values should be annually regulated by the Senate. At the same time the aediles were to restrict the amount of food offered for sale in cooking shops and eating-houses; even banning pastry. And to set an example in his compaign against waste he often served, at formal dinner parties, half-eaten dishes left over from the day before--or only one side of a wild boar--which, he said, contained everything that the other side did.No more kissing! No more pastry! Strict regulation of mullet prices! That's how you bring about a moral reawakening: impose it from above. By the way, Tiberius also opposed tax increases. "A good shepherd shears his flock," wrote the imperial spoilsport, "he does not flay them." Not unless they buy an expensive sofa from IKEA.

He issued an edict against promiscuous kissing and the giving of good-luck gifts at New Year. On the receipt of such a gift he had formerly always returned one four times as valuable, and presented it personally; but he discontinued this practice when he found the whole of January becoming spoilt by a stream of gift-givers who had been denied an audience on New Year's Day.

Tuesday, August 02, 2005

Brief Encounter: Richard Stern

In a career stretching over more than four decades, Richard Stern has produced some of the smartest and most civilized fiction in American letters. Faced with a single paragraph of his prose, early or late, the word that comes to mind is quick, in both its modern sense (speedy) and archaic one (luxuriously alive). It's a sad fact that even books of this caliber go out of print. But happily, Northwestern University Press has now republished three of Stern's gems. Stitch (1965) is a fictionalized portrait of Ezra Pound, butting heads with two aspiring American writers in Venice. Other Men's Daughters (1973) traces the disintegration of a Harvard professor's marriage and his affair with a younger woman--it is, says Philip Roth, "as if Chekhov had written Lolita." And Natural Shocks (1978) brings up the rear with a brisk, brilliant meditation on matters ephemeral (journalism) and eternal (death). From his summer home on Tybee Island, Georgia, Stern recently--and patiently!--answered our questions via email.

In a career stretching over more than four decades, Richard Stern has produced some of the smartest and most civilized fiction in American letters. Faced with a single paragraph of his prose, early or late, the word that comes to mind is quick, in both its modern sense (speedy) and archaic one (luxuriously alive). It's a sad fact that even books of this caliber go out of print. But happily, Northwestern University Press has now republished three of Stern's gems. Stitch (1965) is a fictionalized portrait of Ezra Pound, butting heads with two aspiring American writers in Venice. Other Men's Daughters (1973) traces the disintegration of a Harvard professor's marriage and his affair with a younger woman--it is, says Philip Roth, "as if Chekhov had written Lolita." And Natural Shocks (1978) brings up the rear with a brisk, brilliant meditation on matters ephemeral (journalism) and eternal (death). From his summer home on Tybee Island, Georgia, Stern recently--and patiently!--answered our questions via email. James Marcus: How did you and Northwestern decide to reprint these particular titles?

Richard Stern: Along with Europe, these were the out-of-print novels. One reason for going with Northwestern in the first place (with Pacific Tremors) was their willingness, even eagerness, to reprint the earlier books with fine new forewords, to do the collected stories, and so forth. The other novels are still available.

Marcus: Did you write Stitch, with its quasi-portrait of Ezra Pound, right on the heels of your own encounters with the poet in the early 1960s?

Stern: I was writing a novel with Gunther as the protagonist when I took up my Fulbright assignment in Venice and met the sculptress Joan Fitzgerald, then Pound and Olga Rudge. At that point the novel then took on the dimensions it has.

Marcus: But what initially moved you to turn Pound the poet into Stitch the sculptor?

Stern: I guess it was learning about sculpture from Joan Fitzgerald that had me do Stitch the sculptor. But novel writing teaches you that every departure from actuality spurs the inventive faculty which reportage stifles.

Marcus: Did you ever worry about how the book might be received by the Poundian ménage in Venice? Mary de Rachewiltz, Pound's daughter, certainly contributed a nice blurb.

Stern: Olga Rudge read the book when I returned to Venice in '65 and kept reading, lending and commenting about it, but would not let Ezra read it. (He read in any case and said a couple of unique things about it; don't know if he read anything else of mine.) Mary read it later and wrote the wonderful words which you read. She’s a most remarkable person. Discretions, her memoir about her parents, is a beautiful little book. (Her parents detested it.)

Marcus: I’m afraid you’ve whetted my curiosity. Would you mind sharing what Pound said about your book?

Stern: Pound told Joan Fitzgerald that he’d never read a modern novel which was so involved (wrong verb) with honor.

Marcus: Of your three protagonists, Edward Gunther has the most difficulty escaping the closed circuit of his own personality. "Self-study is a trap," he reflects, "when the self overshadows everything: the sundial eclipsing the sun." Does he ever break free? How about Stitch or your epic poetess, Nina?

Stern: Poor old Edward tries hard but hasn't the firepower to blast out of his own orbit, as both Stitch and Nina have done. They manage to see their own lives in a larger context and thus (I guess the cliche verb is) redeem them.

Marcus: Like the real Pound, the fictional Stitch sees himself as a transmitter of civilization. Are either of them correct?

Stern: Yes, I think both Pound and Stitch, despite making some of the stupidest personal/political decisions a person can make, have advanced/enriched civilization as well as culture. It's the underlying irony--let's say, the ironic fulcrum--of the novel.

Marcus: Before moving on to Other Men's Daughters, I wanted to follow up on your previous comment about actuality and invention. Where in your own work have you departed most dramatically from actuality? Where have you stuck--insofar as a novelist can--to just the facts?

Stern: This is the question most often asked, and it clearly springs from the essential interest in the origin of what's new, what's created. The answers are almost always inadequate. If I had time, I'd go through every sentence of a book and discuss its relationship to what happened to me or to someone I know. The initial invention is the isolation of a situation which has narrative interest. (Sometimes a writer will provoke such situations in his life.) The writer knows that transformation begins the moment such situations bend his temperament and evoke the words and narrative devices which render them.

Marcus: But it's the real-life situations that get the ball rolling?

Stern: I do think that the most moving situations are often at the heart of the most moving narrative moments--but not always. In my early years, I worked mostly from what I imagined. In Any Case derived from a book about the English espionage group S.O.E., but at its heart is the notion of treason, which had special meaning for me back then. (Don't ask.)

Marcus: And how did that process apply to Other Men's Daughters? How, for example, did your protagonist Robert Merriwether become an expert in the physiology of thirst?

Stern: In the summer of 1969, while teaching at Harvard, I read a fascinating technical book on thirst. (I made a point of reading pretty widely, especially when I could follow a subject with an interesting vocabulary.) So Merriwether becomes a Harvard dipsologist. Meanwhile, that same summer, I met the woman to whom I’m now married. Parts of Other Men's Daughters reflect this turnabout in my life (and wife).

Stern: In the summer of 1969, while teaching at Harvard, I read a fascinating technical book on thirst. (I made a point of reading pretty widely, especially when I could follow a subject with an interesting vocabulary.) So Merriwether becomes a Harvard dipsologist. Meanwhile, that same summer, I met the woman to whom I’m now married. Parts of Other Men's Daughters reflect this turnabout in my life (and wife).Marcus: I don't think I've ever read a better, richer description of the woe that is in marriage--at least in its terminal phase.

Stern: Thank you.

Marcus: I find the portrait of Sarah Merriwether especially impressive: she's hateful to the protagonist in some ways, yet still an object of intermittent respect and even love.

Stern: The novel tries very hard to give every character his or her own say. (I was very pleased that the reviewer for Ms. magazine said this was one of the few books by a man that seemed to her fair to women.)

Marcus: Did you ever worry that Sarah might come off as no more than a conjugal millstone around Merriwether's neck?

Stern: No. I knew that would ruin the book. And the underlying reality had some of the complexity the novel examines. Also, I was impressed by Bellow's telling me that writing fiction made you more equitable. I'm not sure that the originals of some of his characters--or mine, for that matter--would agree.

Marcus: Merriwether, contemplating an American-style vita nuova with Cynthia, has his doubts about whether the past can truly be put behind. "The deepest feelings grew down where the nerve foliage reddened, the dendrite thickened," he reflects, in a typically physiological mode. "No new relationship could ever have that."

Stern: The use of your character’s special vocabulary is a great spur to invention.

Marcus: But is he right or wrong about relationships?

Stern: Yes and then no. Every situation is so rich, it's difficult for the writer--as opposed to his character--to generalize this way.

Marcus: A similar question, perhaps: when Merriwether walks up that ravine toward his new life on the last page of Other Men's Daughters, does that constitute a happy ending?

Stern: Again, it's yes and no. Sure, Merriwether is climbing up toward a shining Cynthia, but that doesn’t erase his feelings for the children. The scene in which he embraces his son George is as strong as any in the book--or so I think. But again, the writer does not have a privileged position as his own book's critic. And "happy" is a word that may be too simple for works of art. Music isn't fiction, but does Beethoven’s C-sharp minor quartet have a happy ending?

Marcus: Let's move on to Natural Shocks. Unlike some of the earlier novels, this one seems almost concentric in design: the focus whirls outward from the journalist Frederick Wursup to include Jimmy Doyle, Cicia and her household, Tommy Buell, and so forth. Was that your intention from the beginning, or did this chambered Nautilus of a novel find its own form as it went along?

Stern: A very interesting insight, new to me. One aim was to give the impression if not the weight of a long novel in many fewer pages. (I’m just now suffering the tedium of extra pages in John Irving's A Widow for One Year, which elsewhere has wonderful narrative stretches.) Speculation about what's going on today--set against the element which defines all human life, death--is, I suppose, the basic structure.

Marcus: Wursup is hardly the hack he sometimes makes himself out to be, yet his brand of freewheeling journalism does have voyeuristic or even cannibalistic overtones.

Stern: I think of him as a first-rate journalist, a combination of Halberstam and Lippmann.

Marcus: Where exactly is the dividing line between what a first-rate journalist does and what a first-rate novelist does?

Stern: A journalist is in my view tethered to and bound by what's actually happened. Also, he doesn't have the temporal generosity of an historian or biographer or, for that matter, other social or physical scientists. A novelist has the freedom to do anything which doesn't violate the terms--structure, pace, reality quotient, tone--he's selected for his story.

Marcus: You have, of course, published several volumes of occasional journalism and commentary.

Stern: I’ve enjoyed writing some journalism; it requires very different sorts of alertness, deference, knowledge, responsibility.

Marcus: One last question. Your protagonist Wursup has "goofy storms of feeling," and wonders whether these emotional seizures represent "some passage of soul." He's a materialist to his fingertips, yet he still asks himself whether the material world might fall short in explaining these moments of intensity: "Might there be some quarkish particulate foaming between grosser substances?" I’d like to pose you the same question.

Marcus: One last question. Your protagonist Wursup has "goofy storms of feeling," and wonders whether these emotional seizures represent "some passage of soul." He's a materialist to his fingertips, yet he still asks himself whether the material world might fall short in explaining these moments of intensity: "Might there be some quarkish particulate foaming between grosser substances?" I’d like to pose you the same question.Stern: The material universe is more amazing the more you know about it. But no human mind can possibly answer the ultimate questions it raises. Can flies understand Hamlet?

Marcus: It seems to me that the best novels are devices meant to capture that particulate foaming, the way Franklin trapped electrical charges in his Leyden jar.

Stern: A beautiful image. I suppose the novel is one of the great human attempts to make beautiful sense out of the intricacies, difficulties and paradoxes of human experience, especially of its emotional heights and depths.

Monday, August 01, 2005

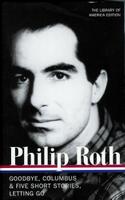

Roth, Last Days

The other day I got the first two volumes of the Philip Roth series from the Library of America: he's the third living author to make the cut, after Eudora Welty and Saul Bellow. Longtime subscribers to LOA will recall the rather chaste jacket art of the initial entries (when your fat, Smyth-sewn edition of Debate on the Constitution: Volume Two showed up in the mailbox, there was no effort to seduce you with eye-catching graphics.) These babies, however, both feature snazzy photos of Roth, first as a Weequahic Lothario with a cushiony underlip, then as the prematurely middle-aged guy who assembled such literary bottle rockets as Portnoy's Complaint and The Breast. Fascinating. Even more fascinating, however, is the precocious brilliance of Goodbye, Columbus, which the author published at the age of 26. Writers twice his age still find it hard to come up with such vivid, funny, anthropologically exact sentences:

The other day I got the first two volumes of the Philip Roth series from the Library of America: he's the third living author to make the cut, after Eudora Welty and Saul Bellow. Longtime subscribers to LOA will recall the rather chaste jacket art of the initial entries (when your fat, Smyth-sewn edition of Debate on the Constitution: Volume Two showed up in the mailbox, there was no effort to seduce you with eye-catching graphics.) These babies, however, both feature snazzy photos of Roth, first as a Weequahic Lothario with a cushiony underlip, then as the prematurely middle-aged guy who assembled such literary bottle rockets as Portnoy's Complaint and The Breast. Fascinating. Even more fascinating, however, is the precocious brilliance of Goodbye, Columbus, which the author published at the age of 26. Writers twice his age still find it hard to come up with such vivid, funny, anthropologically exact sentences:It was, in fact, as though the hundred and eighty feet that the suburbs rose in altitude above Newark brought one closer to heaven, for the sun itself became bigger, lower, and rounder, and soon I was driving past long lawns which seemed to be twirling water on themselves, and past houses where no one sat on the stoops, where the lights were on but no windows open, for those inside, refusing to share the very texture of life with those of us on the outside, regulated with a dial the amounts of moisture that were allowed access to their skin.And to think that he got better as he went along. (Vital trivia: the narrator's name is, of course, Neil Klugman, and the fact that Jack Klugman played Mr. Patimkin in the movie has now introduced just a touch of cognitive dissonance into my reading experience.)

And then there is Last Days, Gus Van Sant's imaginative spin on what we might call Kurt Cobain's exit strategy. The first thirty minutes have a loopy integrity of their own: with nary a line of dialogue, we follow Blake, the Cobain-like protagonist, as he wanders through the woods, pours himself a bowl of Cocoa Puffs, and collapses on the bedroom floor. From the outside, his hilltop mansion resembles a robber baron's wet dream. Inside, with its scabby paint and peeling wallpaper, the place looks like William Burroughs was the decorator. The metaphor--rosy exterior, crumbling interior--fits Blake to perfection. To his credit, however, Van Sant doesn't lean too hard on it. Nor does he inject much pathos or suspense into the situation. It's clear that this guy is going to die, and the only question is: when? What Blake doesn't say--and believe me, he doesn't say much--is conveyed by the long, melancholy, middle-distance shots, the brilliant sound design, and the director's chronological loop-the-loops. Caveat: I was ready for Blake to keel over about a half-hour before the film ended.